It was while studying painting at the Royal College of Art that Tracey Emin became disenchanted with the art of painting, explaining that ‘the idea of being a bourgeois artist, making paintings that just got hung in rich people’s houses, was a really redundant, old fashioned idea that made no sense for the times that we were living in.’ She felt there was no point in making art that someone had made decades or centuries before her – ‘I had to create something totally new or not at all.’ Yet she did not abandon the medium altogether, and it gradually became a way of expressing ideas that were not as easily achieved in pen or pencil.

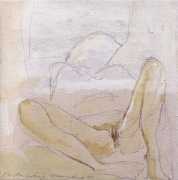

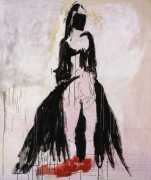

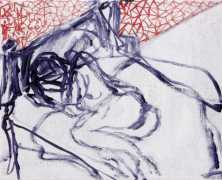

Tracey Emin’s paintings occupy a different emotional register from her drawings, even as they engage many of the same themes of desire, vulnerability and embodiment. Where her drawings hinge on immediacy and the fragile precision of line, her paintings thicken those impulses into something more atmospheric and corporeal. The brush becomes a broader, more forceful instrument than her pen, allowing her to explore erotic experience not just as gesture but as emotional saturations of colour and mood.

In these works Emin often uses sweeping strokes, blurred contours, and areas of pigment that feel bruised or tender, capturing both the body and the emotional residue surrounding it. Her figures appear submerged or emerging from in colour fields, suggesting the way erotic memory can feel both enveloping and difficult to retrieve. Unlike the quick, trembling lines of her drawings, the paintings’ sensuality resides not just in the subject but in the act of painting itself. Emin’s paintings extend her erotic language into a more immersive and affective realm. They visualise the interior turbulence of intimacy, offering eroticism as something elemental and enveloping rather than merely delineated.

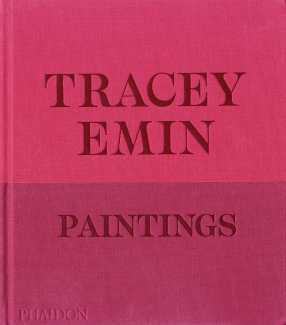

In 2024 Phaidon Press published a detailed study of Tracey Emin’s paintings, with text by fellow artists David Dawson and Jennifer Higgie. At the end of the book is an extended discussion between Dawson and Emin, from which we have extracted a few of the pertinent sections. For the complete conversation – and to see more than 300 of Emin’s paintings – we strongly recommend that you get hold of a copy of Tracey Emin: Paintings.

In 2024 Phaidon Press published a detailed study of Tracey Emin’s paintings, with text by fellow artists David Dawson and Jennifer Higgie. At the end of the book is an extended discussion between Dawson and Emin, from which we have extracted a few of the pertinent sections. For the complete conversation – and to see more than 300 of Emin’s paintings – we strongly recommend that you get hold of a copy of Tracey Emin: Paintings.

What is it that you search for when you make a painting that you feel is successful: an answer to a certain question?

Sometimes you can paint a really successful picture, and it’s in your own language and it just kind of slipped out. You’ve got to make sure you get it back, because it’s not warranted. It shouldn’t exist – it already exists.

It’s a real balancing act – like being on a trapeze wire?

Totally.

It’s what’s authentic or what’s real and what’s been seen before in your psyche?

Yeah, it’s in the psyche. It’s not just on a gallery wall, it’s within me. It’s like, when we curate a show, an external curator might go, ‘I really want to put this painting next to that painting’, and I say, ‘Why?’ And they say, ‘Oh, because they look really good together’, and I go, ‘You can’t put them together because it would be morally wrong.’ They’re just looking at the colours and what it looks like, but they don’t know what I know about what’s underneath and what it’s gone through and where it started. I’ve got one painting of me carrying my mum’s ashes, which I painted over, and then somehow – don’t ask me how – it ended up with me being fucked up the ass or something. Really hardcore. I had to paint over it because I didn’t want to have that, even though it’s still there now in between the layers. I had to move it on. It’d be so funny if in years to come my paintings were X-rayed.

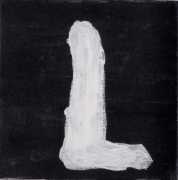

Then each layer would come through. And the white paint you use as a colour is another veil, isn’t it, for multi-layered thoughts and patterns to come through?

Sometimes I’ll put the white primer on after the paint and use it that way. Or sometimes I do a painting, and I put paint over the whole thing – not with white paint but with the white gesso primer – and I’ll do it thin, and then I’ll let the whole painting bleed through and come up to the top, and then I’ll paint another painting over it.

You’ll always know it’s there.

I’ll always know it’s there, exactly. And with painting, it’s always about how do you go forward?

A painting does take a long time. It concentrates and develops and condenses through time, doesn’t it, through spending time with it?

Also, one of the weirdest things that happens: paintings literally need to settle. Breathe and settle. It sounds so pretentious, but only people who really paint know what I’m saying. Paintings move, they shift, they have this other energy. They do something.

Do you think your concentrating on your inner thoughts means that the subject is always you?

I think I’m painting about, and trying to understand, emotions that are quite universal. So that’s why my work relates to other people. The way we’re talking about it now sounds quite pretentious, but this is for a specific reason. I have to explain myself, how I think and how I do things. I’d be doing myself an injustice if I didn’t explain it in detail and where it all comes from. Basically, a lot of people who don’t know anything about painting or don’t know anything about art can look at my work and get it – and they don’t just get it visually, they get it emotionally. They feel something.

I still remember the paintings you did at the Royal College of Art when we were there together – they weren’t as large as these, but you had your grandmother in many of them, which is still the same thing you’re painting now.

Yeah, it is, totally, except now it doesn’t look like Byzantine frescos crossed with Edvard Munch.

Did you destroy them for practical reasons because you didn’t have any money and you didn’t have anywhere to store them? Or did you destroy them because you knew by destroying them, the future work you made would be better for it?

It was a combination of anger and knowing that I couldn’t take care of them. I couldn’t look after them, and subconsciously I didn’t want anyone else to have them. I also think the fact that I was pregnant had a lot to do with it. I was going to have an abortion. So if I couldn’t look after a child, how could I look after these paintings? Actually, maybe it’s the other way around – it should be the other way around! But yes, to me it was as important as a child. Now, would it be better if we had twenty paintings from the Royal College of Art that I made? Would it be historically important? Would it really matter? Would it matter to anybody? I don’t know.

Was that the only reason you stopped painting?

I also think the reason why I stopped painting was a combination of things, like the abortions, definitely. Big, big, big things. I couldn’t stand the smell of oil paint when I was pregnant, or turps or anything like that, and I thought I’d go back to it. But then I realised that I didn’t feel justified in painting because I felt so angry with myself about lots of different things. I kind of punished myself – I stopped doing the thing I loved doing most. It was a good thing in a strange way because now my painting isn’t just a basic progression. It’s a complete re-evaluation of everything and why I do it. But I didn’t really stop for that long.

What about the words you regularly use on the canvas?

I write a lot and I’ve always written a lot. Now and again words come through on these canvases, but not as much anymore. I did a painting the other month that said, ‘How the fuck do you think I feel?’ It was good, actually, and that’s the last painting I put text on.

The titles are as strong as ever. How do the titles come about, just as you’re working?

After I finish. I have a working title for a painting: ‘The Sailing Boat’ or ‘Pyramid’. After I finish the painting, I often title it something more poetic and more thoughtful and more meaningful to me. But what’s really annoying is that then I continue to call it ‘The Egg Timer’, or whatever it was.

Time condensed into painting is one of the most important factors, isn’t it? You said it a long time ago: a lot of painting is waiting.

It is, isn’t it? I’m lucky enough now to have canvases and space and room to paint, which is a really good thing because if I had all the paintings in here that I’ve done in this studio it’d be chock-a-block. It’d be crammed. I don’t want to work like that anymore. I love working with nothing in the room – not loads of paint and not loads of stuff and not loads of gubbins. All my stuff is upstairs, and I don’t see it. When I get all my storage sorted out properly all that gubbins will be arranged like a library. It will be immaculate, my archive, and then I’ll have upstairs free to do the tiny paintings.

Freedom is so important.

The other thing about how I paint: I’ll be painting on that canvas and then suddenly I can move over to this one. Or I’ll be painting on that and then I’ll move to this. Or I mix up a really nice colour to go on that, but it’s the wrong colour, so I put it on that. I’m moving backwards and forwards, and then sometimes I have just a little bit of paint left, so I get a tiny brush and I do this sort of feathery thing with it.

You’re working very well in the studio in London as well though, aren’t you?

I love it, and I also work really well in France. People say to me, ‘Why do you want all this shit?’ And I go, ‘Well, Picasso had about eight studios. Nobody had a go at him.’ You can make it seasonal or you can depend on your mood. In London, I make those amazing small paintings, which here I haven’t done. I started some, but they’re different here. They’re bigger. They’re not bigger in size – they’re bigger in brush, bigger in attitude somehow, not so myopic.

It’s a good word for the small paintings, ‘myopic’.

Really looking in.