I Modi – the archetypal Italian Renaissance erotic portfolio

Pietro Aretino’s Sonetti Lussuriosi (Lustful Sonnets) or I Modi (The Positions), as you will discover when you read about them below, hold a unique position in erotic literature, and in erotic illustration. For many years they were the benchmark, both actual and perceived, for the most daring, realistic and provocatively erotic of imaginations, and given the importance still given in some sexual circles to sexual ‘positions’, notably with the revival of interest in the Kama Sutra in the 1970s, you could say that the subject matter is as fresh and relevant now as it was in the mid-sixteenth century. Plus ça change …

The text below includes the relevant section about Pietro Aretino and I Modi by Ian Moulton of Arizona State University, included in Gaëtan Brulotte and John Phillips’ monumental Encyclopedia of Erotic Literature, and an exploration of the illustrated French revival of the work in 1904.

Another French attempt to capitalise on the reputation of the I Modi illustrations, by the eccentric ‘Count’ Jean-Frédéric Maximilien de Waldeck in 1856, can be found here.

Aretino and I Modi

Pietro Aretino (1492–1556), poet, novelist and essayist, was one of the most influential and financially successful men of letters in sixteenth-century Italy, and an almost mythical figure in the history of European erotic writing. He first gained notoriety in Rome in the mid-1520s with the Sonetti Lussuriosi, a series of ‘lustful sonnets’ he wrote to accompany sixteen erotic engravings produced by Marcantonio Raimondi after drawings by Giulio Romano. The sonnets describe sexual activities and desires in clear, non-metaphoric language, and although they were quickly suppressed they became notorious throughout Europe. Although Aretino’s name was synonymous with erotic writing and pictures well into the nineteenth century, the majority of his texts were not, in fact, erotic. After the sonnets and some other early poems, his major erotic work was the Ragionamenti, or Dialogues, written in Venice in the mid-1530s.

Pietro Aretino (1492–1556), poet, novelist and essayist, was one of the most influential and financially successful men of letters in sixteenth-century Italy, and an almost mythical figure in the history of European erotic writing. He first gained notoriety in Rome in the mid-1520s with the Sonetti Lussuriosi, a series of ‘lustful sonnets’ he wrote to accompany sixteen erotic engravings produced by Marcantonio Raimondi after drawings by Giulio Romano. The sonnets describe sexual activities and desires in clear, non-metaphoric language, and although they were quickly suppressed they became notorious throughout Europe. Although Aretino’s name was synonymous with erotic writing and pictures well into the nineteenth century, the majority of his texts were not, in fact, erotic. After the sonnets and some other early poems, his major erotic work was the Ragionamenti, or Dialogues, written in Venice in the mid-1530s.

Aretino first attained public notoriety after the death of Leo X in 1522, when he wrote a series of satirical poems opposing the election of the foreign Pope Adrian VI and supporting the candidacy of his new patron, Cardinal Giuliano de’ Medici, the future Clement VII. These poems, often quite bawdy and crude, were known as ‘pasquinades’, because they were affixed anonymously to a battered old statue near Piazza Navona called Pasquino. It is unlikely that Aretino initiated this practice, which persisted throughout the sixteenth century and beyond, but more than anyone else he was identified with the poems. Indeed, when Adrian VI took power, Aretino found it prudent to leave the city.

Adrian was pope for only two years, and Aretino returned to Rome after the election of his patron as Pope Clement VII in 1523. But he was soon in the midst of a new controversy. His friend Raimondi, a renowned Italian engraver, was imprisoned by the pope’s counsellor, Giovanni Matteo Giberti, for having made the sixteen erotic prints based on Romano. The court of Clement VII was not at all prudish. But while erotic drawings and paintings might be tolerated and even enjoyed within the relatively closed aristocratic world of the court, erotic engravings, which could be printed in large quantity, sold in the marketplace, and widely disseminated beyond the court, were another matter altogether. At a time when Lutheran criticism of papal corruption was spreading all over Europe, the Pope could not afford to have such materials associated with the Vatican.

Aretino petitioned the pope for Raimondi’s release, and then, once his friend was safely out of jail, he wrote a series of sixteen erotic sonnets – the Sonetti – to accompany the engravings. Together, the sonnets and engravings were known as I Modi (the modes or postures) because each portrayed a man and a woman having intercourse in a different position. The history of the sonnets’ dissemination is very difficult to trace with any accuracy, because the printing took place surreptitiously and most copies have been destroyed. At first, the sonnets probably circulated in manuscript, written by hand on the printed sheets of the engravings. While it was long thought that an edition of poems and engravings was printed in Rome in 1525, Bette Talvacchia has argued convincingly that the first printed edition was probably produced in Venice in 1527. No copies of this edition are known to exist. The earliest surviving edition is another one, probably printed in Venice the same year, but with crude woodcuts replacing the elegant engravings. Only one of the original sixteen engravings is now extant.

Aretino’s sonnets are the most important and influential erotic texts of the sixteenth century, not because of their content – significant though it is – but because of their sheer notoriety. Few copies were printed, and almost none survived the papacy’s attempt to suppress them; but although few people read them, everyone heard of them. As time passed, the role of Raimondi and Romano was largely forgotten, and the engravings became known as ‘Aretino’s pictures’, a phrase which was soon synonymous with erotic art or text of any kind. In Shakespeare’s day, ‘aretine’ was an English adjective and ‘to aretinise’ was an English verb. In Elizabethan England, Aretino became an almost mythical figure of erotic excess. John Donne included him in a list of damned Catholic innovators, including Machiavelli; Ben Jonson used him as a model for his most famous character, Volpone: Thomas Nashe, a ranting satirist, took to calling himself ‘the English Aretine’.

Raimondi’s engravings are groundbreaking in that they depict naked couples having sex without recourse to any mythological trappings. The figures are clearly men and women, not gods and nymphs. Similarly, the language of Aretino’s sonnets is straightforward and slangy rather than elevated and formal. Sex is described using crude everyday words without the aid of elaborate metaphors. As befits poems written to explicate images, the sonnets are more descriptive than narrative. They are almost all written in dialogue form – the men and women in the pictures converse as they have sex. They tell each other what they like and what they don’t like. They celebrate their pleasures and make fun of their rivals. The couples engage in both vaginal and anal intercourse; neither practice is declared superior. The sonnets do not propose any hierarchy of positions or claim that any one position is natural. There is no depiction of oral sex or manual stimulation without penetration. The fundamental purpose of the poems would appear to be a celebration of the pleasures of heterosexual intercourse.

But in this case, appearances are deceiving. The sonnets cannot be understood outside of the political context which produced them. Aretino’s writing of the sonnets was a slap in the face to those who had imprisoned Raimondi, and constituted a serious attempt to embarrass the papal court at a time of heightened social and political tension. Not only was Luther’s revolt against Church authority gaining strength throughout Europe, the pope was also on the verge of war with the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V – a conflict which would lead to the sack of Rome two years later. Aretino was no Protestant, but he was outraged at the mistreatment of his friend and the hypocrisy of the papal court. In a public letter written to justify his writing of the sonnets, he contrasts official persecution of I Modi with tolerance of corruption:

What harm is there in seeing a man mount a woman? ... The thing nature gave us to preserve the race ... has produced all the ... Titians, and the Michelangelos; and after them the Popes, the Emperors, and the Kings ... And so we should consecrate special vigils and feast-days in its honor, and not enclose it in a scrap of cloth or silk. One’s hands should rightly be kept hidden, because they wager money, sign false testimony, lend usuriously, gesture obscenely, rend, destroy, strike blows, wound, and kill.

Here Aretino ironically praises the penis, but in the sonnets female genitalia receive equal praise and attention. In most cases, the speeches are equally divided between male and female speakers. While some of the engravings stress the man’s aggressive strength, as a group the sonnets do not suggest masculine domination of the sexual encounter. In several sonnets the woman directs the man on how best to please her. And although the sex in some is fairly rough, none of the sonnets represents a rape. In most, both partners seem to take equal sexual pleasure. The following exchange from the first sonnet is typical:

[He]: Let’s fuck, my love, let’s fuck quickly,

Since we are all born to fuck.

If you adore the cock, I love the cunt ...

[She]: But let’s stop babbling and ram your cock

All the way to my heart.

Aretino’s audacity in supporting Raimondi infuriated many at court, especially Papal Secretary Giberti, the official who had imprisoned Raimondi. On the night of July 28, 1525, Aretino was attacked by Achille della Volta, a gentleman in Giberti’s service, and left for dead with serious injuries in his chest and hand. As soon as he had recovered enough to travel, Aretino left Rome. After a year or so spent mostly in Mantua, he settled in Venice in 1527.

For anyone interested in exploring the erotic in Italian renaissance culture, art historian Bette Talvacchia’s Taking Positions is a fascinating read. Her study focuses on the I Modi engravings, showing how drawings, printing technology, censorship and religious teachings about sex combined in sixteenth-century Rome to create a unique set of circumstances which led to the creation of this milestone in renaissance erotica.

For anyone interested in exploring the erotic in Italian renaissance culture, art historian Bette Talvacchia’s Taking Positions is a fascinating read. Her study focuses on the I Modi engravings, showing how drawings, printing technology, censorship and religious teachings about sex combined in sixteenth-century Rome to create a unique set of circumstances which led to the creation of this milestone in renaissance erotica.

A valuable appendix to the book gives the Italian text of each of Aretino’s sonnets, together with the best available (prose) translation into English.

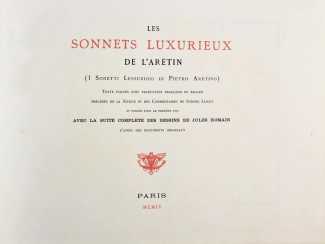

In 1904 a large-format edition of I Modi was produced in Paris with a set of ‘engravings after Marcantonio Raimondi’, together with matching coloured illustrations by Édouard-Henri Avril. The text used was that of the 1882 edition of Aretino produced by the Paris bookseller/publisher Isidore Liseux, but the purpose of the new edition was more to sell the illustrations and the French translations of the sonnets than to introduce its readership to Liseux’s learned text.

In 1904 a large-format edition of I Modi was produced in Paris with a set of ‘engravings after Marcantonio Raimondi’, together with matching coloured illustrations by Édouard-Henri Avril. The text used was that of the 1882 edition of Aretino produced by the Paris bookseller/publisher Isidore Liseux, but the purpose of the new edition was more to sell the illustrations and the French translations of the sonnets than to introduce its readership to Liseux’s learned text.

The portfolios shown here are the ‘reconstructions’ of the Raimondi engravings, together with Avril’s interpretations. Also included is a set of engravings of I Modi by the Italian engraver Agostino Carracci.

The story of how the ‘Raimondi’ drawings were found in a chateau in southern France, recounted in the introduction to the 1904 edition, is well worth reproducing in full. How much of it is true is anyone’s guess.

From the introduction to the 1904 edition of Sonetti Lussuriosi

Liseux, who published so many excellently printed, edited and annotated books on the Italian fifteenth century, was a modest scholar, withdrawn from the world, careless of fortune. His editions, which he was not sufficiently commercially-minded nor fortunate enough to sustain, did not receive the recognition they deserved, for all were conscientiously made with a rare concern for typographic purity for which our age is no longer suited. Liseux was the last writer-publisher of the school of great masters of yesteryear. The poor fellow, so locked in his studies, indulgent to all, talking little and not envious of the reputations of others, will not see the success of his books; but the hour is not far distant when his publications, scrupulously produced in small editions, well annotated and beautifully presented, will attract both scarcity and high price.

The scholars of history, to whom this book is addressed in a more particular manner, possess sufficient biographical documents on Italy, so it would be useless to introduce them again to the complex figure of the legendary Aretino. We will not, therefore, add anything to the conscientious work that our learned brother Isidore Liseux has devoted to him, contenting ourselves with reproducing in full the text of his notes on the Sonetti Lussuriosi, for collectors of bibliographical curiosities who could not, in 1882, obtain one of the hundred copies printed for the publisher and his friends.

But a new chapter has been added to the history of the prints that gave birth to the sonnets of Aretino, and the recent discovery of a series of engravings, evidently copied from the original engravings by Marcantonio Raimondi, brings a new dimension to the sagacious compiler. We owe it to all those art lovers and bibliophiles who have kindly helped us to uncover the present edition some details on how the engravings which accompany our collection have fallen into our hands, their origins, and the proof that they are authentic.

We are obliged to warn our readers that it is not possible for us to offer for their admiration the original suite of the famous engravings engraved by Raimondi in 1525 from the drawings of Julius Romano. This suite must have been marvellous, judging from the few vestiges that remain. The engravings shown here are therefore reconstructions executed by a skilful draughtsman whose role was limited to completing, without changing a stroke, the old engravings which we placed at his disposal.

The reproductions shown here follow all the details of the originals, though reduced to half their original size for the convenience of our format, and they are placed opposite the sonnets to which they relate. Everything leads us to believe that they were taken directly on an original copy of I modi by an artist who had the good fortune to contemplate these rare compositions and the good spirit to keep a lasting memory of them.

The story of their discovery can be told in a few words. It was during a stay in the Gers region of southern France that we had the good fortune to come across the sketches drawn on sheets of thin paper which are the basis of the illustrations laid out in our edition. The old-fashioned style of these sketches, the yellowed tone of the ink, and the wrinkled edges of the paper gave a clear sense of their age.

A closer examination of this collection of voluptuous figures convinced us that it was a studied and careful work, and not a fortuitous assemblage of fanciful sketches from the pen of a libertine artist. Besides, each piece had a number, a writing differing from that of the copyist, and the whole suite was contained in a wallet showing traces of wax seals, on which could be read ‘Di Romano’.

Di Romano! The perfect concordance of the postures and the text of the Sonetti Lussuriosi gave us the best possible clue as to their origin. The subjects of the engravings matched exactly to the sonnets, and the numbers of the former were repeated on the others, in the same order assigned to them by the oldest editions. The artist who had copied the figures, or, in his absence, the one who had numbered them, must thus have had knowledge of the original text of Aretino, and attributed to each of his sketches the number of the corresponding verses.

So where did this collection of licentious drawings come from, whose present possessor, little versed in literature, had completely ignored their importance and artistic value? Here is what we learned.

Their first owner was the Comte d’Esclignac, one of the gentlemen of King Louis XVI, who was attached to the Superintendent of Fine Arts. Like all the refined men of his age, the count possessed a superb library and a gallery of the ornaments of an enlightened taste; his duties brought him in constant contact with the best artists, and he received famous painters and sculptors who embellished his castle. When the turmoil of 1792 broke out, the count emigrated, abandoning the family castle and the rich lands he possessed in the bishopric of Lonsbe. His property was confiscated and sold.

A certain Joseph Barozzio, a rich farmer of Italian origin, bought the seigneurial dwelling, promising to return it to its original owner when the exiles returned to their homeland. The count did not return until 1871, and was deeply grateful to the honest man who had preserved his patrimony. In place of a pecuniary remuneration, which Barozzio refused, the Comte d’Esclignac vowed to him a eternal friendship, and insisted that he accept some of the artistic treasures from the chateau.

Thus the worthy farmer, fond of art like any good Italian, found his house decorated with two portraits painted by Madame Vigée-Lebrun, a painting by Poussin, some drawings by Raphael, and a manuscript atlas drawn by Sébastien Lepresle de Vauban, who had been tutor to the Duke of Burgundy.

It is in the pages of this atlas that were inserted the sixteen erotic engravings that now occupy us. During his long exile, the Comte d’Esclignac had doubtless forgotten all about them, and Barozzio, on receiving the gift of the great lord, his friend, dared not mention the presence of these drawings.

At Barozzio’s death the inheritance passed into the hands of his eldest son, who passed it on to his son, the grandson of Barozzio. The grandson lost all of his fortune in unhappy speculation, and in 1884 was obliged to sell all that he possessed. The paintings and other items were bought at a low prices, and the atlas and its clandestine contents became, for a ridiculously small sum, the property of our collaborator in the present work.

It remains for us to ask the indulgence of our subscribers for the artist who executed the reconstructions. He was not unaware of the difficulty of his undertaking, and was afraid that his temerity might have surpassed his talent in this attempt to imitate an inimitable master.