The Czech-born painter and illustrator Marie Čermínová, better known as Toyen (usually thought to refer to the French word citoyen, citizen), had origins that both she and her circle enjoyed being deliberately mysterious about. Whatever the truth about her family, her class origins and her gender, by the time she left the Prague Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in 1920 at the age of eighteen, she was determined not to be limited by any of them.

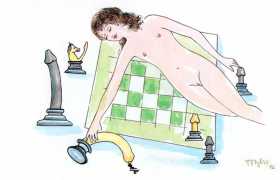

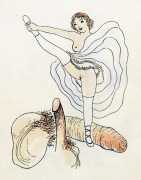

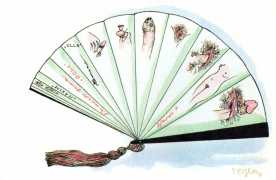

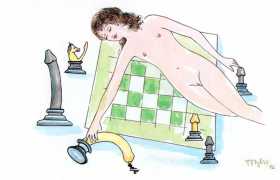

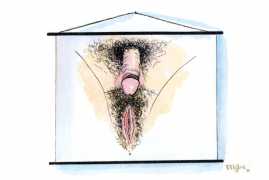

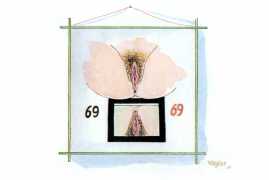

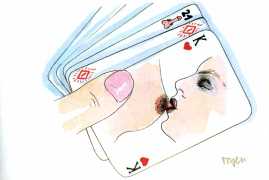

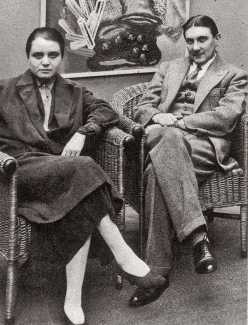

During the 1920s Toyen was developing her particular style of drawing and painting along surrealist lines, being influenced and in turn influencing both French and Czech fellow-artists. She worked very closely with poet and artist Jindřich Štyrský, who you can read more about here; the two joined the Prague-based Devětsil group in 1923, and from 1925 to 1928 they worked together in Paris, where Toyen had already spent some time in 1921. Her paintings and illustrations were frequently erotic, and in the early 1930s she regularly contributed erotic sketches for Štyrský’s Erotická revue and Edice 69.

The 1930s were heady times for Toyen, Štyrský and their circle of Czech and French friends and colleagues. Together with Vítězslav Nezval and Jindřich Honzl they founded the Czech Surrealist Group, developing their own distinct style. As the only truly independent woman in the group, Toyen was determined that she should hold her own as a person and as an artist, and in order to achieve that she insisted on being labelled and categorised as little as possible. Her ‘ungendered’ name helped, as did her choice to wear whatever she felt matched her current state of mind and her short-cropped hair. While she had important intimate relationships with men, she insisted on being free to relate with whoever she chose; this has sometimes resulted in her being claimed as bisexual or transgender, but the truth is that she was a risk-taking free spirit who was fascinated by the complexities of gender, sexuality and intimacy but did her utmost not to be limited by convention. Her choice not to be limited as a woman meant casting aside the confining trappings of femininity in order to access the almost exclusively male modernist art world, and to be taken seriously as an artist.

Štyrský’s death in 1942 was a bitter blow to Toyen, though by then she had also developed a crucially important artistic relationship with fellow Czech Jindřich Heisler, a poet of Jewish descent who had joined the Czech Surrealist Group in 1938. Before the Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1948 they moved to Paris, where they worked with André Breton, Benjamin Péret, and other French and Czech surrealists.

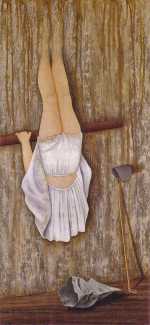

Toyen’s life’s work as an artist is a much larger subject than can be addressed more than superficially here; we concentrate on her illustration work with a specifically erotic edge, which interestingly stopped being so important to her after the late 1930s. Many of her later paintings display a personal response to her social and political world, but are less explicitly sexual. She continued to paint powerful, personal responses to a world she knew to be dangerous and unsettled, especially for a woman and a refugee from Soviet totalitarianism, but surrealism as a style faded in the post-war years, and Toyen’s work only started to be recognised again in the 1980s.

Remarkably there has never been a proper biography or illustrated monograph about Toyen and her work; in 1953 a slim volume was published by the Czech emigré Paris publishers Sokolova entitled Toyen, which included essays by André Breton, Jindřich Heisler and Benjamin Péret, and in 1980 the Pompidou Centre in Paris produced an extended catalogue, Štyrský, Toyen, Heisler, to accompany a retrospective exhibition.

Fortunately Toyen does have a very thorough and readable biographer in Karla Huebner, who wrote her 2008 University of Pittsburgh postgraduate thesis on Toyen and her world, and her excellent study, Eroticism, Identity, and Cultural Context: Toyen and the Prague Avant-Garde, can be read online here. Karla, who is now Associate Professor in Art History at Pittsburgh, has also written In Pursuit of Toyen: Feminist Biography in an Art-Historical Context, which you can read here.

Fortunately Toyen does have a very thorough and readable biographer in Karla Huebner, who wrote her 2008 University of Pittsburgh postgraduate thesis on Toyen and her world, and her excellent study, Eroticism, Identity, and Cultural Context: Toyen and the Prague Avant-Garde, can be read online here. Karla, who is now Associate Professor in Art History at Pittsburgh, has also written In Pursuit of Toyen: Feminist Biography in an Art-Historical Context, which you can read here.

To whet your appetite, here are some selected extracts from Karla’s Eroticism, Identity, and Cultural Context.

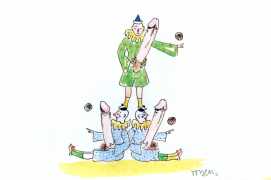

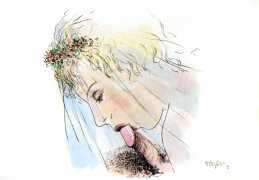

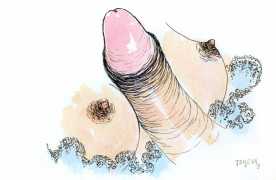

Toyen differed from most of her female peers in her depiction of erotic themes. Male surrealist exploration of the erotic is one of the most striking features of both surrealist art and writing, and given the vital role that the sexual and erotic were theorized to play in the liberation of the human spirit, this is hardly surprising. Certainly, the women in and close to the movement gave the erotic an important role and were more willing to present explicit sexual imagery than were most women outside surrealism. At the same time, women’s art was hardly a mirror image of the men’s; women associated with surrealism never eroticized the image of the male to the degree that male surrealists did the female. For example, while Valentine Hugo created a few erotic works employing the male body, this was never a major theme for her. Likewise, Leonor Fini’s depictions of sleeping or quiescent males relate more to myth than to eros as a transformative force. Toyen’s phallic imagery is thus perhaps the only work by a surrealist woman that uses the body of the opposite sex to explore sexuality in a manner at all similar to the men’s use of the female body.

In recent literature, Toyen’s personal sexuality, not surprisingly, continues to be mythologized, but is increasingly heterosexualized. Her relationships with Štyrský and Heisler have been assumed to be sexual ones, although Nezval states that she insisted she and Štyrský were merely friends. Various efforts have also been made to supply Toyen with mysterious possible male lovers, such as a reference to ‘the presence of a young man of dark complexion’ encountered by Czech art historians who visited her in the early 1960s. Zuzana Krupičková similarly notes that some inhabitants of Saint-Cirque Lapopie speculated eagerly about the handsome driver who always dropped Toyen off in the village, but Krupičková was able to learn that the driver was simply Elisa Breton’s secretary. The recent Jan Němec film Toyen portrays the artist as obsessed with Jindřich Heisler and implies that he was involved in the creation of heterosexual erotica made when he was in fact barely adult.

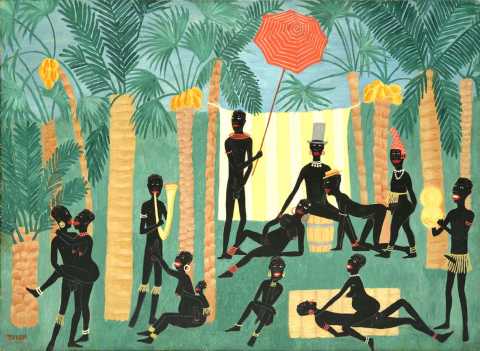

Many women in the early avant-garde, if not so many in Prague, presented themselves as lesbian, bisexual, or simply opposed to old codes of femininity. Few, however, were as bold in their artistic representations of gender and sexuality. Very few took on these themes in art at an early age. Toyen’s oeuvre includes a significant body of erotica, both in the form of book illustrations and as personal sketches and oil paintings. These date back to at least 1922, or in other words to the very beginning of her career. While works such as Pillow and Paradise of the Blacks do not seem to have been publicly shown, Toyen quickly became a well-known illustrator and even her anonymous erotic drawings in Štyrský’s Erotická revue were probably easily recognizable to readers who knew her mainstream illustrations or bought her signed erotic titles.

In 1925, Toyen thoroughly explored the sexuality that she appears to have associated with Parisian liberty. Sketch after sketch from that year testifies to her thoroughness. Though her move to the city with Štyrský is recalled by their friends as occurring in the fall, she had gone on an earlier French trip in December 1924, and dated sketches show that she was in Paris at least between mid-January and March of 1925. In her early French sketchbooks, Toyen experimented with a wide variety of sexual imagery, including lesbian activities, sailors spraying nude women with semen, men masturbating in the company of women, and even bestiality. An intriguing parallel to some of her sketches of sailors and prostitutes can be found in Kiki de Montparnasse (Alice Prin)’s sketches of a February 1925 trip to Villefranche. Villefranche, a port reserved for foreign military ships, was full of American sailors from the S.S. Pittsburgh and their prostitute camp-followers, and the irrepressible Kiki acquainted herself with both sailors and prostitutes, whom she apparently recorded in a sketch diary much like Toyen’s. Kiki’s published sketches are dated 1929 rather than 1925, so may have been refined from a sketchbook or may even have been inspired by works by Toyen seen during the 1920s. In any case, Toyen could hardly have missed hearing about the celebrated Kiki’s Villefranche adventure, which must have been the talk of the Montparnasse cafés during Toyen’s early 1925 visit.

By the end of the nineteenth century, if not well before then, Paris had acquired an international reputation as a kind of sex mecca, where prostitution, eroticized entertainment, enticing lingerie, relatively explicit marriage manuals, nude models, hysterics in wild abandon, and crossdressers could readily be found. It was also a city where sexual difference was to some degree tolerated. Although Rosa Bonheur had been obliged to obtain a permit to wear trousers, cross-dressing was not uncommon for women of subsequent generations, and by the end of the nineteenth century there is considerable evidence of open lesbian groups and venues.

If Toyen was seeking a lesbian-friendly milieu, Paris was decidedly a locale with a recent history of toleration and even fashionability. Male nineteenth-century writers such as Baudelaire, Gautier, and Louÿs, as well as Remy de Gourmont, Zola, and others, featured lesbian themes prominently, as had female authors including Rachilde, Jane de la Vaudère, Colette, and Renée Vivien.

The American (but Francophone) poet Natalie Barney provided a meeting place for a highly international and primarily lesbian collection of writers and artists. Active for sixty years, her salon was extremely popular among the literary, and an invitation to it ‘bestowed immediate cachet’. Barney herself visited the Bureau of Surrealist Research during the 1920s, although she does not seem to have had other ties to surrealism. Still, although Barney’s salon was thriving in the 1920s and 1930s, it may have seemed old-fashioned and politically conservative to Toyen, even if she was able to get an invitation.

Indeed, by the 1920s many names of notable Paris lesbian couples come to mind, among them Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Djuna Barnes and Thelma Wood, Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) and Bryher (Winifred Ellerman), Janet Flanner and Solita Solano, Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier, and Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap. Well of Loneliness author Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge, while not resident in Paris, spent extended periods there. The bisexual painter Tamara de Lempicka moved to Montparnasse in 1920. The Danish artist Gerda Wegener, now best known for her marriage to early male-to-female sex-change recipient Einar Wegener and for her mostly lesbian-themed erotic illustrations, also lived in Paris during the 1920s. And, though it is unknown whether Toyen became acquainted with any of the major lights of the literary Left Bank lesbian scene, she could have acquired a copy of Djuna Barnes’ scandalous Ladies Almanack, privately published in 1928 and available at Shakespeare and Company or on the street. One thing is clear from this list: expatriates made up a visible part of the larger scene, although the writings of Colette make clear that French women had their own, perhaps separate, venues. Claude Cahun and her lover Suzanne Malherbe/Marcel Moore had settled in Montparnasse in the early 1920s.

Parisian lesbian life was relatively acceptable among the artistic. But more dangerous sexual adventures could be found by women who chose to seek them. The artist Tamara de Lempicka often went out to parties and clubs until midnight, where she took cocaine and flirted heavily with dance partners of both sexes, and then, giving the impression that she was going home to her husband and daughter, made ‘forays to the hastily constructed dirt-floored lean-tos that dotted the Seine’s bank.’ Here, in ‘shabby clubs’ that attracted a mix of sailors, male and female students, and the occasional society woman, she participated in group sex with sailors and young women. The fact that some of Toyen’s erotic sketches of this period depict sailors suggests that she too may have ventured into these haunts. She may also, like Anaïs Nin, have explored Paris brothels, either alone or with Štyrský.