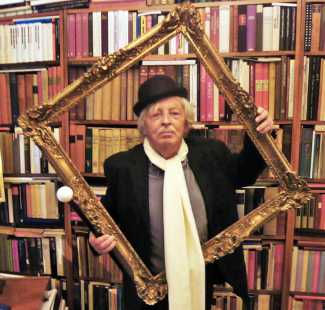

Conversations with Hans-Jürgen, Part 2

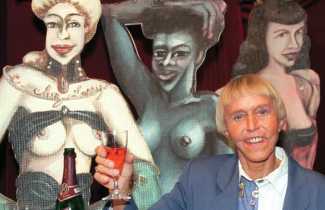

Nobody knows more about erotic art than Hans-Jürgen Döpp. His many books include 1000 Erotic Works of Genius, Objects of Desire, The Kiss, Temple of Venus and Paris Eros.

Hans-Jürgen is based in Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany, and for many years taught sociology at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University. As well as collecting, teaching and writing he has curated many exhibitions and helped develop and collect for several erotic art museums.

He now publishes a wide range of specialist publications under the Venusberg imprint (www.venusberg.de). After fifty years of careful gathering he has amassed a large and fascinating erotic art collection.

Look out for Part 3 of Hans-Jürgen’s interview, coming soon.

Tell us about your collection of erotic art, how you collect, and how you record and share it.

There is no culture in the world that hasn’t produced fascinating erotic works of art, and in the spirit of being interested in everything I started collecting Japanese woodcuts, Indian miniatures, Peruvian ceramics – and much more. Quite soon I realised that some of the objects were simply too big, so I started being more selective, and gave the larger things to other collectors. I also realised that affordability was a sad but necessary limitation. So I chose to limit myself to European erotic portfolios, thus remaining loyal to my first purchase, the Bellmer Sade.

Next I made some further important decisions. I decided not to collect books if they were written in French, for the simple reason that I couldn’t read them. I decided that I wouldn’t collect portfolios so large that they could only be presented in an exhibition. And I also decided that I wouldn’t hide my collection away as ‘my secret property’, that I wanted to share it as felt appropriate.

I never intended to compile an encyclopedia of erotic art to include every direction and aspect of art. A good collection is a living organism that is constantly changing. The discovery of the particular qualities of a work made me increasingly discriminating; I was continually looking at what I had collected to assure myself that as well as being good technically it wasn’t just so much kitsch.

Every collection has its own personal profile. There are collectors whose collection resembles a summer meadow, with every kind of flower in full bloom. Then there are collectors who are fixated on just one subject; this is often their secret core fantasy. There are collectors who only collect spanking art, or art featuring large buttocks; I even know of one who especially loves scenes in which women look at their own behinds in a mirror. I sometimes wonder if he is trying to recall his childhood memories.

In old age my standards have become even stricter. It makes me wonder if in the end my extreme discrimination might leave me with just one picture, but a picture I would never have found if I hadn’t collected and looked carefully at ten thousand images!

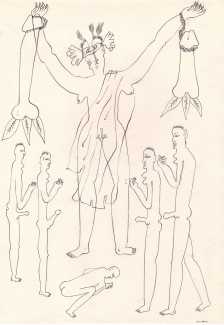

I am particularly cautious when it comes to contemporary art. I am often encouraged by artists to purchase something from them. A solution I have found for myself is that when I discover an artist I feel has something special to offer, I commission them to create a series of illustrations for my favourite book, Georges Bataille’s Histoire de l’oeil. The book was first illustrated by André Masson, then by Hans Bellmer. I now have some around eighteen portfolios of my own for this important experimental work.

I have been fortunate over the years to be able to forge deeper friendships with some of these contemporary artists. In particular I would mention Martina Kügler, who died three years ago; I knew her for forty years, and admired and collected her works. Her work has had a lasting impact on my understanding of art.

And of course with such a large collection there are always the issues of cataloguing and storage. It became clear that keeping important information about artists and their work on small pieces of paper made searching very difficult, so the creation of a computer database has been very important. Sometimes I feel that I am less of a collector and more of an administrative clerk!

And to solve the storage problem I decided to rent a locker at my bank, but I soon realised that whenever I wanted to show a collector friend something important it wasn’t available. So I took everything home again, and now the art has taken over most of the cupboards and shelves, even the box under the bed. It feels important to have my collection near me.

Tell us more about the Venusberg project, what you have achieved and what you plan for it.

I know collectors who guard their erotic works like a secret treasure. One old collector friend, now deceased, confessed that he had many friends and acquaintances who still don’t know what he was collecting!

I have always believed that a collection shouldn’t be a secret, and one way of making it public is through the publication of books. I know this is somewhat of an antiquated decision for the digital age, but a book is a sensual object that you can touch. My ‘big’ books like The Erotic Museum and The Temple of Venus, published at the end of the nineties, were very successful; they appeared at the end of a liberal era and introduced readers to art they had never seen before. In that same period, however, the production of pornography increased exponentially, and as the internet gained in importance, providing instant gratification, the ‘alibi’ of art for those who had previously sought access to sexually arousing images via the printed page rapidly lost much of its appeal.

So not much chance for erotic art then, or was there? At the beginning of the new millennium I set up an internet-based ‘museum’ under the name Venusberg, to be a showcase for pictures from three centuries of European erotic art, with access via a payment system. But I soon discovered that the effort was out of all proportion to the reward. Why would people pay for erotic imagery when they have free access to so many porn sites?

But I remain firmly attached to the form of the book. Since the internet has also made it possible to design books myself and for the books to be created print-on-demand, I have gradually been making portfolios of some of my collection available on paper again. It’s a slow process, but I have had moderate success and a small but loyal following of collectors.

Tell us about the Berlin Erotic Museum and how it came about; what is its current status?

Spurred on by the success of the Amsterdam Erotic Museum, the Beate Uhse Group came up with the idea of founding an Erotic Museum in Berlin. One day at the end of 1994 I received a call from Beate Uhse. Beate had been the only female stunt pilot in Germany in the 1930s, and after World War II she set up the first sex shop in the world.

She asked me to come to Flensburg and evaluate a collection of 120 boxes of erotic art that she had acquired. It took me three days to give her the honest advice she needed but found it hard to accept – to throw all of it into the Baltic Sea. It was all just replicas and fakes, mostly fakes of kitsch. But since a property had already been rented for the museum and the opening date had been set, I was set a year-long task of buying up entire collections, including some excellent exhibits.

At the end of 1995 the museum opened with great success. In the first year things went so well that Beata thought of opening a second museum in Milan or Madrid. The entire inventory of another, smaller but valuable, erotic museum was bought, which I had helped a close friend in Cologne to establish.

But the success of the Berlin museum waned over the years, and the company made no effort to revitalise it with specialist exhibitions and interesting acquisitions in order to attract new audiences. The inventory of the Cologne museum was stored in a cellar in Flensburg and forgotten. It was now clear to me that it wasn’t a love of art that drove Beata’s project, it was nothing more than a business idea that was supposed to make the sex shop next to it more attractive.

In January 2020 the museum’s entire holdings were auctioned at an auction house in Berlin. Here, too, I worked as a consultant, and so I went from being the museum’s midwife to being its gravedigger.

What do you now think about Museums of Erotica like the Barcelona Museum and the Wilzig Erotic Art Museum? Do they have a useful future?

One day an elderly woman showed up at the Paris fleamarket in Clignancourt, wearing a sign round her neck that said ‘I am looking for erotic art’. It was Madame Wilzig. She bought everything the European collectors had left behind. Now the World Erotic Art Museum in South Beach near Miami is advertising in Trumpian tones ‘This is your unique opportunity to view the greatest collection of erotica you will ever see!’ To me it feels like an ‘anything goes’ sort of place, lacking any real sense of historical awareness, the power of the rare, the real and the beautiful. It’s more of a mishmash than a collection.

The Erotic Museum in Barcelona opened in 1997. It is entirely geared towards tourist tastes. You get your money’s worth as a passing voyeur, but not a lot as a collector. The Musee de l’Erotisme in Paris was also opened in 1997. In addition to changing exhibitions of contemporary artists, it represented all cultures of the world in a colourful variety. But it didn’t last the course, and in August 2016 its holdings were auctioned off.

By contrast, the Amsterdam Sex Museum, the Temple of Venus, has remained successful over the years. Apart from the fact that the whole city is a single advertisement for the museum due to its red-light reputation, knowledge, money, time, and above all love, the prerequisites for its foundation from the beginning, have ensured its success.

By contrast, the Amsterdam Sex Museum, the Temple of Venus, has remained successful over the years. Apart from the fact that the whole city is a single advertisement for the museum due to its red-light reputation, knowledge, money, time, and above all love, the prerequisites for its foundation from the beginning, have ensured its success.

Compared with these museums, open to the general public, the Cologne collector Dieter Engel spent ten years creating a precious cabinet of curiosities of erotic art extending over twelve rooms. Not for him the hoi polloi; he didn’t want an audience, only connoisseurs and selected guests were granted access. All the time he was collecting I was privileged to work with him in an advisory capacity. Sadly this great patron and true lover of art died in April 2020.

Many of the most important works of erotic art are locked away in museum collections; isn't it a pity that they are not available for study and appreciation by a wider audience?

In 1846 the poet Charles Baudelaire wrote ‘How often, when presented in galleries with so many similar representations of “good taste”, was the desire of the poet, the art lover, the philosopher, for a museum of love where the whole of the subject was represented, from the tenderness of Saint Thérèse to the debauchery of the broadest imagination.’ Baudelaire’s vision of a public museum of erotic art remains a utopia to this day.

If you go to the Frankfurt Städel Museum and ask about works by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, Willi Geiger or Johann Heinrich Ramberg in their collection, they will tell you they have nothing. Yet these are the masters of German erotic art. From Thomas Rowlandson, the master of erotic caricature, there is – a landscape with a stagecoach. The reason for this is the puritanical buying policy of most museums. Only museums in cities with a more liberal past have had the chance to incorporate erotic works or collections. Thus you will find a lot of erotic art in the Louvre, and in Munich in 1819 the Royal State Library was able to buy the erotic library of the Bavarian tax officer Franz von Krenner. There it was stored separately and locked away from the general public.

The Munich library’s handling of erotic art is typical; while the books in the Krenner collection were added to the library’s holdings, the images were banished to the cellar of the graphic collection, in a box with the inscription ‘Unusable; not inventoried’. At one point I made the museum, which like all other museums is always in financial need, an offer to purchase the box. The answer was completely expected: ‘Since the collection was gifted to a public museum it must be retained’.

The handling of erotic art in the Hermitage in St Petersburg is just as perverse. I was given the privilege of being able to glimpse the erotic treasures there: hundreds of lithographs from the period from 1835 to 1850 – Lithographies Romantiques – which were probably confiscated from aristocratic property at the time of the Revolution. According to an attached list, only ‘deserving officers’ were allowed to see this secret collection against a signature. What a sensation it would be to exhibit these works in Europe under the title ‘The Erotic Treasures of the Hermitage’. But the museum is embarrassed that they own them!

Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts has a more intelligent policy. In 2012 the collector Julio Mario Santo Domingo bequeathed his library to it. Known as the Ludlow–Santo Domingo Library, it is ‘the world’s largest private collection of material on altered states of mind’, and includes a large collection of French erotica. Unlike the other ‘public’ collections, it is open to researchers.

In the last part of this interview, Hans-Jürgen will talk about the impact of the internet on erotic art, society’s changes in relation to sexuality, what he has learned as he gets older and wiser – and which erotic images are his all-time favourites.