Conversations with Hans-Jürgen, Part 3

Here is the third and last part of our interview with Hans-Jürgen Döpp, in which he shares his thoughts about erotica today, the influence of the internet, how he defines erotica – and which are his favourite erotic images of all time.

Nobody knows more about erotic art than Hans-Jürgen. His many books include 1000 Erotic Works of Genius, Objects of Desire, The Kiss, Temple of Venus and Paris Eros. He is based in Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany, and for many years taught sociology at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University. As well as collecting, teaching and writing he has curated many exhibitions and helped develop and collect for several erotic art museums.

He now publishes a wide range of specialist publications under the Venusberg imprint (www.venusberg.de). After fifty years of careful gathering he has amassed a large and fascinating erotic art collection.

There seems to be little new erotic illustration and publishing now compared with the period from around 1920 to 1950; why do you think that is?

Erotic art has always been a rebellious art. It accompanied the process of enlightenment and the emergence of modernity, and was accompanied by a large number of court cases. In the dark years of fascism, however, its life-breath was cut off. It was not until the 1960s that a process of liberalisation began again, which brought a new spring for erotic art in the last decades of the twentieth century. A healthy approach to life also seemed to liberate its erotic aspects. What was overlooked, however, was a dialectical change in sexual morality – ‘You mustn’t want sex!’ tended to become ‘You must want sex!’ Sexuality changed from a form of rebellion to the basis of consumerism.

The excitement that accompanied erotic art in the 1960s was due largely to the fact that it had been surrounded for centuries by the aura of the forbidden and secret. With freedom, however, the prohibition that had made it so exciting fell away. Erotic art now drew its tension from the provocative feeling of transgression, but over time that too gradually dissipated. The trend today appears to be a kind of listless lust. Sexologists are finding a decrease in erotic desire and pleasure everywhere; more and more people are turning to therapy to ‘find out what is wrong’ with their lack of desire. What the Catholic church tried to achieve for centuries through oppression appears to have been achieved today through too much emphasis on the sexual, which in turn has led to an exorcism of the erotic.

What changes do you think the growth of the internet, and especially of internet porn, have had on erotic art and illustration?

Eroticism consists of slow, subtle detours. Immediacy is its enemy. Sexual desire that is sated in seconds will never be more than animalistic.

Consumerism and sexualisation today go hand in hand, to the extent that much advertising verges on the pornographic. Sexual references are everywhere, and sexuality in the form of pornography is widely available, especially through the internet. If eroticism is based on the stimulation of imagination by filling the gap between desire and fulfilment, then pornography robs us of imagination by its immediacy. Erotic art, however, thrives on imagination.

In most pornography, sexuality is only displayed in its genitally-fixated, aggressive form. Against the background of gender-specific social criticism, women tend to appear in pornography only in relation to the man who defines them. The phallus, a symbol of fertility and creativity in ancient times, becomes a signifier only of male dominance. The vagina becomes little more than a space to be occupied by a penis, rather than the source of life and sensual energy.

Theodor Adorno recognised the dangers of sexual utopia drowning in the primacy of genitality. He defended ‘those who cling to the perverse emphasis of erotic variety over genitality’, and who represent in art the imaginative, the refined, the socially perverse and indecent.

How do you think society’s ideas have changed in the last twenty years in relation to sexual pleasure, gender relationships, kink, desire, the commercialisation of sex, and people’s understanding of the role of the erotic in their lives?

Between the 1970s and 90s a sociable image of sexuality tended to dominate. This picture darkened in the years that followed – AIDS sounded alarm bells; an assertive feminism highlighted patriarchal violence in sexual relationships and denounced much erotic art as misogynistic macho fantasy; sexuality became increasingly associated with rape and child abuse. Under the influence of American puritanism, censorship of erotic art became widespread. In 2006 the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London removed the naked dolls of the surrealist Hans Bellmer from its exhibition ‘so as not to shock the Muslim population of the area’.

Some of my books on erotic art were rejected by a publisher because they were ‘incompatible with the publisher’s business principles’. When asked, they replied that many of the books are sold by Amazon, a distributor steeped in the American spirit of puritanism, for whom sexuality is something dirty. Nietzsche’s words ring out: ‘Christianity gave Eros poison to drink’.

Eroticism and sexuality today are often met by a sea of hostility. Rather than an exploration of shared desire and pleasure, sex tends to have become akin to a health-promoting sport. When it is seen purely as functional, coitus kills desire. For anyone who is interested in the full range of intimate human experience, this is a disturbing trend which continually needs to be challenged.

How has getting older and becoming more mature influenced your thoughts about what older people can usefully learn and experiment with in the area of intimacy and the erotic?

Aging offers a renewed chance to appreciate art, and particularly erotic art. As the immediacy of physical arousal tends to diminish, it becomes possible to appreciate more the aesthetic and formal aspects of a work of art. The eye has the chance to look at a work with, as Kant puts it, ‘disinterested pleasure’. Of course, the erotic impulse can still be aroused when a representation meets a core fantasy. When this happens, I sometimes try turning the picture upside down so I am no longer distracted by the representation itself and can concentrate on the formal quality of the work!

This doesn’t necessarily mean that people in old age approach erotic art more confidently. The sight of beauty can embitter those for whom life has denied the joy of intimate love. They may be frightened by desires which will forever remain unfulfilled. Such indignation can often be understood as a postponed form of unmet and unexplored sexuality; for such people erotica remains forever alien.

Erotic art is always a risk. Anyone who gets involved with it inevitably becomes an enemy of convention. Maybe erotic art will always be an interest limited to ‘the happy few’, but I believe the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer had it right when he wrote of his envy of the collector of erotic art. ‘In old age,’ he wrote, ‘there is no better consolation than knowing that one has absorbed the whole power of one’s youth into works that do not age’.

If you had to choose just six pieces of art that are your absolute favourites, which would they be?

Wilhelm von Kaulbach, ‘Robert Blum’, 1848

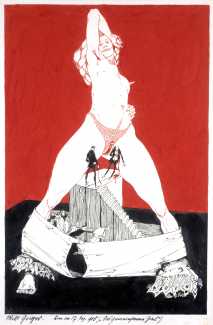

Willi Geiger, The Common Purpose, 1905

Jules Pascin, ‘Reclining Girl’, 1928

Hans Bellmer, À Sade, 1961

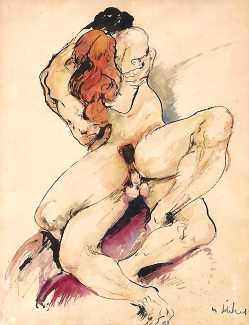

Willy Jaeckel, Watercolour, 1925

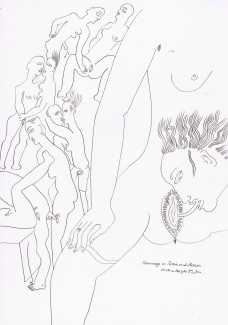

Martina Kügler, Pencil drawing, 1995

This is so difficult for me! Otto Schoff is also one of my favourites, and the talented hand of Otto Rudolf Schatz — and I wouldn‘t want to miss out Leo Putz, or the old Lithographies Romantiques … It’s an unfair question!

With all your years of thinking about it, how would you now define ‘erotica’?

Sexuality is a natural drive that humans and animals have in common, but the mere act of copulation has nothing to do with eroticism. What distinguishes us as human are awareness, imagination and fantasy. Watching a couple having sex on video isn’t necessarily erotic at all. We know nothing of their desires, their fantasies about domination and submission, their longing to be loved. This is where the eroticism comes in, the pleasure of experiencing intimacy from much more than a merely voyeuristic, cinematographic point of view.

Eroticism is a long-haul phenomenon. It loves the detour rather than the direct route to its goal. It thrives on everything that goes beyond the immediate satisfaction of instincts, like the slow untying of a corset or the longing look. So it may be that a foot fetishist, a lover of corsets, and many others who we might call ‘perverts’, have a better sense of the erotic than those who head straight for their goal of satisfaction. Art is an indirect stimulus – it appeals first to the eye, then to the mind, and then – and only maybe – manifests in physical arousal.

Take a bare breast for example. It can represent a sexual stimulus (unless maybe seen from the perspective of the mammograph), but in itself it is about as erotic as the sight of a bald head might suggest a ghost. To become erotic it might be that the breast is being slowly revealed; it is the dialectic of coquettish unveiling and revealing that makes it the object of erotic desire. If you want to drive out the erotic, then start out stark naked.

Is there any difference between eroticism in art and sex in art? When asked what the difference between erotic and non-erotic art is, Picasso once said after some thought, ‘All art is erotic – if it is not erotic, it is not art!’ By the same argument, the opposite of erotic art is not pornography, it is non-art.