In Paris in the last years of the nineteenth century and the first of the twentieth, the studio art nudes of Antoine Calbet were exactly what the public wanted, colourful, youthful, slightly risqué but not too much so, and very easy to understand. And what the public wanted Calbet was quite ready to provide, in bulk. But Calbet, unlike some of his contemporaries, was immensely talented and versatile – his legacy extends to book and magazine illustration, and most easily-accessible and well-known, the delightful panels depicting the cities of Nice, Evian, Nîmes and Grenoble which were commissioned for the luxurious Train Bleu restaurant at Paris’s Gare de Lyon.

In Paris in the last years of the nineteenth century and the first of the twentieth, the studio art nudes of Antoine Calbet were exactly what the public wanted, colourful, youthful, slightly risqué but not too much so, and very easy to understand. And what the public wanted Calbet was quite ready to provide, in bulk. But Calbet, unlike some of his contemporaries, was immensely talented and versatile – his legacy extends to book and magazine illustration, and most easily-accessible and well-known, the delightful panels depicting the cities of Nice, Evian, Nîmes and Grenoble which were commissioned for the luxurious Train Bleu restaurant at Paris’s Gare de Lyon.

Antoine Calbet grew up in Engayrac in the Lot-et-Garonne region of southern France. Displaying an early talent for art he first studied in Montpellier and then at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he enrolled in the atelier of Alexandre Cabanel, whose notorious ‘Birth of Venus’ won plaudits and a gold medal in the Salon of 1863 – from which Manet’s ‘Déjeuner sur l’herbe’ was rejected. Calbet acquired a slick and skillful academic technique to which he added elements borrowed from Degas and the Impressionists. Making his Salon debut in 1880, he enjoyed a highly successful career, winning several medals including a silver in the Paris World Exhibition of 1900, in which Gustav Klimt and Joaquín Sorolla also won medals.

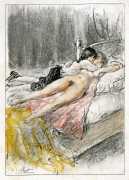

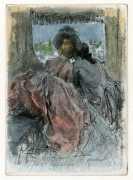

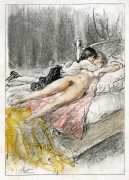

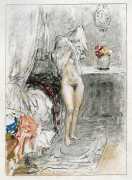

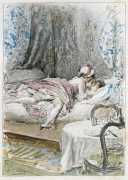

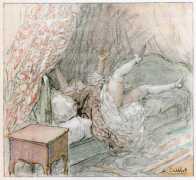

The set-piece Salon nudes that won Calbet so much success in his lifetime now look rather gaudy and vulgar. The simpering smiles and clichéd poses make the pictures voyeuristic and slightly pornographic. So it comes as a surprise to many to learn what a subtle observer of modern life he was when working as an illustrator. He may have regarded his work as an illustrator of popular novels and magazines like L’Illustration as a pot-boiling sideline, but in many ways this is precisely where his true talent lay. His simple technique of working in charcoal heightened with white chalk and gouache on tinted paper enabled him to achieve extraordinary effects of light and atmosphere and of mood.

We know very little about Calbet’s private and social life beyond his artistic output. He never married or had children, but would have had more or less intimate friendships with both women and men. The blatant eroticism of his Salon paintings attest to the heterosexuality of the artist and his clientele, but his work as an illustrator indicates a far more wide-ranging and nuanced attitude. Amongst the authors with whom Calbet worked were the flamboyantly homosexual Jean Lorrain, pioneer of gay fiction, and Pierre Louÿs, whose work evinced a life-long obsession with lesbianism.