When, in the golden days of pre-internet, someone suggested seductively that you ‘Come up and see my etchings’, you had a pretty good idea what they meant. And those etchings, if they actually existed, were almost certainly French, early twentieth-century, and un peu érotique.

When, in the golden days of pre-internet, someone suggested seductively that you ‘Come up and see my etchings’, you had a pretty good idea what they meant. And those etchings, if they actually existed, were almost certainly French, early twentieth-century, and un peu érotique.

Etching, in French eau-forte, was in that period an essentially French art form. During the mid-nineteenth century, etching experienced a widespread revival among French artists. Although the medium had been in use for centuries, interest in it had waned by 1800 alongside the invention of lithography and the developing popularity of reproductive engraving. By the 1860s, however, etching was embraced as a reaction against the negative associations of these media with industry and mass production. Produced by sketching on a malleable wax ground or thin varnish instead of carving into a copper plate, etching more closely resembled the practice of drawing, and was seen as directly connected to the artist’s hand. Etchers were also often more involved in the printing of their works, and could select inks, papers and processes themselves or in collaboration with a master printer. These qualities led etching to be viewed as more authentic, artistic and expressive than other printmaking processes.

Building on etching’s developing reputation as an expressive and artistic technique, the publisher Alfred Cadart (1828–75) and printer Auguste Delâtre (1822–1907) formed an official society for the medium in 1862. The Société des Aquafortistes aimed to promote etching to both artists and the general public, and by the early years of the twentieth century the techniques, ethos and quality of etching had matured. It was a perfect time for self-taught Auguste Brouet to enter the scene.

Brouet’s early life, while not comfortable (he grew up with his grandmother in the eastern Paris suburb of Les Lilas while his parents, a seamstress mother and itinerant chemical worker father, sorted out their turbulent marriage in Montmartre), gave him direct experience of the bustle and variety of the city. When he was eleven he was apprenticed to a lithographic printer, and at fourteen to an Italian lutemaker. He took an evening class in drawing, and encouraged by friends who had worked with the great Auguste Delâtre experimented with needle and acid, thus discovering his love for etching.

By 1905 his work had greatly improved in quality, and he started to find a ready market for his prints of Paris scenes, both landscapes and his trademark street scenes featuring occupations like market traders, mistletoe sellers, acrobats and circus folk. The Great War provided more opportunities for sensitively-executed patriotic themes, and by the early 1920s Brouet had become a key figure in the Paris artistic scene. In January 1925 the critic Noël Clément-Janin wrote of him ‘Auguste Brouet is a real artist. He expresses himself in the most direct manner. His lines have a limpid quality and reflect the utmost simplicity. It places Brouet among the four or five French etchers whose work is most sought after.’

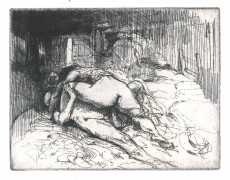

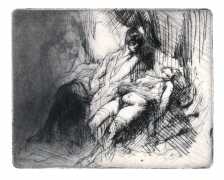

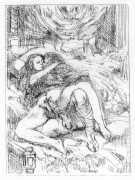

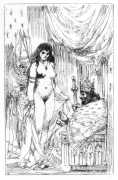

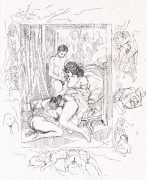

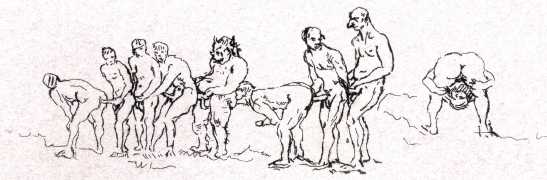

It was probably his studies of dancers that brought Brouet’s skills to the attention of the collectors of limited-edition print editions of erotic texts, and to publishers comfortable with such material like Gaston Boutitie and René Bonnel. Close-up studies of bodies, especially naked ones, was not particularly Brouet’s forte, but he was always open to a challenge. Where he lived all his adult life, near the top of Montmartre, was an ideal location for studying his subjects in the flesh, and though we know little of his rather single (though very sociable) life, he created some touching and sensitive intimate scenes for the three specifically erotic portfolios he made between 1926 and 1938.

For much more information about Brouet, including images of many of his engravings, biography and period background, the place to go is the Auguste Brouet Journal website, which you will find here.