In her trademark paintings known for their hyper-realistic rendering and explicit scenes, American artist Betty Tompkins presents unabashed portrayals of female sexuality. Text and language also feature largely in her work, seeking to confront the history of misogyny in the art world and the ongoing objectification of women.

In her trademark paintings known for their hyper-realistic rendering and explicit scenes, American artist Betty Tompkins presents unabashed portrayals of female sexuality. Text and language also feature largely in her work, seeking to confront the history of misogyny in the art world and the ongoing objectification of women.

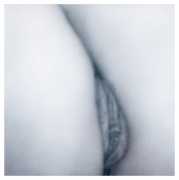

Betty grew up in Washington, and studied at Syracuse University and Washington State University. She began to consider sex as the subject of her paintings in the late 1960s while going through her then-husband’s collection of pornographic magazine images. After selecting and cropping ones she found compelling, she started recreating them. Between 1969 and 1974, a series of eight ‘Fuck Paintings’ was created using an airbrush, building upon layers of black and white acrylic paint to depict close-up shots of penetration. These were followed by ‘Cunt Paintings’, ‘Penetration Paintings’ and ‘Masturbation Paintings’. Monochromatic and slightly out of focus, Tompkin’s canvases are evocative formal studies, tending towards abstraction.

Although Tompkins was able to exhibit her early paintings in the 1970s, she remained in relative obscurity for decades. In the 1970s in New York, galleries refused to show her artworks, while many second-wave feminists denounced the works for what they perceived as being exploitative of women. Her paintings also suffered from censorship; in 1973, two were seized by the French Customs Office on their way to France for an exhibition. It took a year before the work was returned to the artist.

Tompkins later began to work closely with text. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, she drew phrases from legal United States documents and painted their enlarged reproductions in acrylic or pencil. The US Constituion and Bill of Rights were frequent sources.

Tompkins first received the attention she deserved in 2002, when one of her paintings was purchased by the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the series was shown at the Lyon Contemporary Art Biennale in 2003. Her work was reconsidered in the context of feminist art, which led to her inclusion in the group exhibition ‘Black Sheep Feminism: The Art of Sexual Politics’ at Dallas Contemporary in 2016.

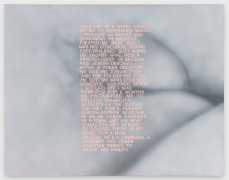

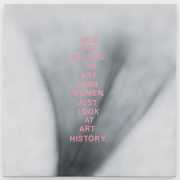

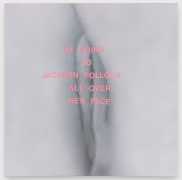

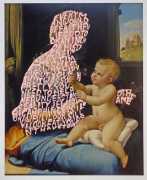

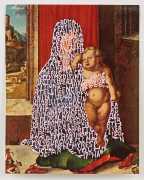

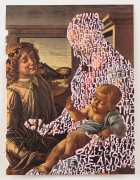

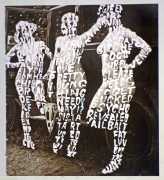

Since the early 2000s Tompkins has revisited the subject matter of sex, highlighting it in terms of violence against women. In 2002, she initiated ‘Women Words’, which asked people to send in emails showcasing language they heard in relation to women. A second ‘Women Words’ series followed in 2013. In ‘Women Words’, artistic masterpieces by male artists such as Titian’s ‘Venus and Adonis’ and Manet’s ‘The Surprised Nymph’ have the female figures covered in pink text, bringing attention to the way the female body has been objectified under the male gaze. A complementary series entitled ‘Apologia’, started in 2018, takes works by female artists and blocks out the male figures with text.

Betty Tompkins has lived and worked for many years in New York, where she has her studio.

In November 2017 Betty was interviewed by Charlotte Jansen for Elle magazine; her replies to the questions give a good sense of her as both woman and artist.

Your art is so provocative, it's so in your face …

I’ve been told that on a scale from conservative to way out, I’m past way out. Which is a surprise to me, because all I do is get up every morning and do what I want.

How did you first get involved in the feminist movement in New York?

I never wasa formal member of the early feminist movement. I was ignored by them; some of them had real problems with where I got my source material.

Where did you get it from?

I was using my husband’s pornography. They had a two-fold objection, first was that I was embracing the pleasure principle above everything else, and second that the models were paid, and there were people who think that if you did porn, then or now, you were inevitably being exploited. I’ve never used material where my sense of the people involved was exploitation – my sense is, they’re getting paid, they’re working, but also they’re having a really good time, and that was one of my first takes on porn. When I first saw it when I was 21 years old, and thought, ‘they look like they're having fun. Let's all have fun!’ I guess in the 1970s that kind of sentiment wasn’t acceptable to hard-line feminists. Their history of course informs mine, but I was never invited to meetings. This was way before the internet, so back then this was how it was done. They put signs up in Fanelli’s, which is the little bar-restaurant across the street from me in Soho, and when I was in my 20s and 30s you would go and look on their bulletin board. It was a closed group. I would’ve gone if I’d been invited, but I never had the opportunity.

You stopped making your large-scale cunt and fuck paintings, which you started in the seventies, for quite some time

I did, I left it for a couple of decades. I couldn’t get anywhere. I was young – when I left it I was 29, 30 – and it was hard to get shown as a young artist. I was a woman, young, and making work about sex. I was the wrong of everything.

Why did you start working with text and words?

I was totally disgusted with the critical discourse at the time. Critics would always talk about being able to ‘read’ the work. So I thought, let’s give them something to read.

How did your original women words project come about?

I got the idea in 2002. I sent an email to everyone I knew that I wanted to do a series about language and women. I asked people to send me their words and phrases about women. It was also a new idea for me to reach out to the world and say ‘send me stuff’, and my god they did! I got more than 1,500 responses, in seven different languages.

How did you come back to it in 2012?

We were at my studio discussing Jason Rhoades and his use of language, and I started to talk about mine. I went over to a table with a pile of books and papers on it and lifted up a book and then there they were – exactly where I’d left them ten years ago. Housekeeping is not my forte. I decided to do one thousand paintings of the words. I began to wonder then if language had changed – eleven years had gone by, things were supposedly different – so I sent another email out, this time promising people anonymity, which I hadn’t before. I don't know if that’s why, but I got so many stories back. The four most repeated words were exactly the same as first time round – bitch, cunt, slut and mother.

A lot of anger, violence and frustration towards women comes out through this process of audience participation. How do you deal with that?

I have a really good sense of humour, and I think it’s saving my life – and my blood pressure! There was one guy who had written ‘the only thing that would make her more beautiful would be my dick in her mouth’, and I thought, who is this guy? You have to laugh.

Interestingly you also don't know if these have been written by men or women

Oh yeah, deleted and embedded misogyny is a real thing, as we’ve seen. These serial abusers, harassers, rapists, have often had help – women helped them. And we have to start to ask how, how did this happen? It's something I’ve been aware of for a really long time, but I’ve only recently begun to get articulate about it in my work.

Revelations about sexual abuse have also been happening in the art world, are you surprised?

When I started to do my paintings, no matter who it was, I always made sure I wasn’t the only person in my loft. When I was in college a professor of mine said to me, ‘the only way you're going to make it as an artist is flat on your back’. That’s an incredible thing to say to a twenty-year-old. The first time I went to see a dealer in New York, what that professor had said popped into my head going up in the elevator. I got so scared then when I got out I went to the bathroom and threw up instead of going into the gallery. Even though my joke became that women dealers were only interested in the boys, men dealers were only interested in the boys, and no-one was interested in women artists, that was always in the back of my mind. Lucky for me no-one wanted to talk to me anyway!

Nobody understood what you were doing for so many years. How do you keep going?

Stick to it and do what you want, what you believe in. In the long run it’ll do well by you.

Betty Tompkins’ Instagram account can be found here.