One of the most original and stylish illustrators of 1920s Paris, Charles Laborde was born in Buenos Aires, the youngest of the five sons of Adolphe-Sylvestre Laborde-Pinou, a millionaire who had made a fortune selling luxury goods imported from France to wealthy Argentinians. The family returned to France when Charles was six months old. His mother died when he was two, and as his father was often away on business and his brothers at boarding school, he spent his childhood at their family Château d’Escout in the Pyrenees largely left to his own devices. Though it was a lonely childhood, he was the darling of his generous and magnanimous father and his brother Jean-Felix. He learned to draw encouraged by a local artist, and frequently accompanied his father visiting artisans and choosing luxury objects to be sold in Argentine.

One of the most original and stylish illustrators of 1920s Paris, Charles Laborde was born in Buenos Aires, the youngest of the five sons of Adolphe-Sylvestre Laborde-Pinou, a millionaire who had made a fortune selling luxury goods imported from France to wealthy Argentinians. The family returned to France when Charles was six months old. His mother died when he was two, and as his father was often away on business and his brothers at boarding school, he spent his childhood at their family Château d’Escout in the Pyrenees largely left to his own devices. Though it was a lonely childhood, he was the darling of his generous and magnanimous father and his brother Jean-Felix. He learned to draw encouraged by a local artist, and frequently accompanied his father visiting artisans and choosing luxury objects to be sold in Argentine.

Charles first attended the Rollin College in Paris, then a lyceum in Pau, where he lived with full board and lodging after his father’s death in 1901. He knew he wanted to be an artist, and tried several pseudonyms – Ch. Laborde, Carlos Laborde, Carlos Edrobal and Carl Lab. At seventeen the timid shortsighted teenager wearing big glasses was expelled from college for smoking and drinking alcohol, and moved back to Paris to live with Jean-Felix, who carried on his father’s business. Charles enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian, studying under Henri Royer and Marcel Baschet; he was also a pupil of William Bouguereau and Luc-Olivier Merson at l’École des Beaux-Arts.

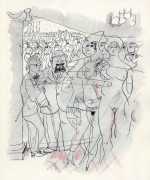

In England, where he stayed each year from 1905 to 1914 with the family of his friend Cooper, a classmate at the Académie Julian, he found not only his pseudonym Chas, but also the land of his dreams. The peculiarities of London and its inhabitants reflected in drawings of William Hogarth and Thomas Rowlandson later prompted Charles to make his London Street Scenes.

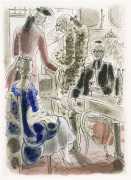

In 1905 the Château d’Escout and the Buenos Aires company were sold, and coming into his inheritance Laborde became financially independent and established an atelier in Montmartre at 11 rue des Saules. His neighbours were de la Butte, Francis Carco and Pierre Mac Orlan, who sympathised with the easy-going young man with a positive attitude to life. His friend Pierre Falke introduced him to the labyrinthine world of illustrated magazines, and Laborde regularly received commissions from the satirical magazines Le Rire and L’Assiette au Beurre. In 1912 he moved to Le Sourire magazine where he joined the influential artist Gus Bofa.

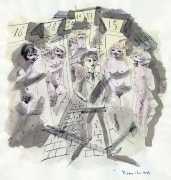

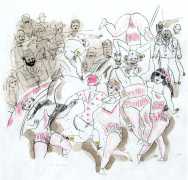

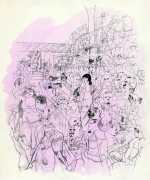

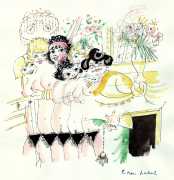

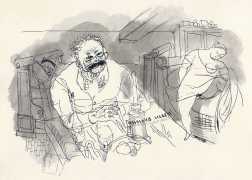

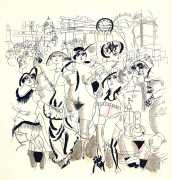

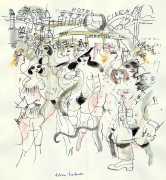

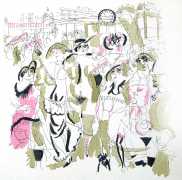

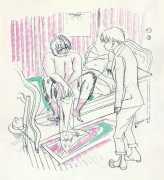

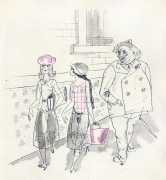

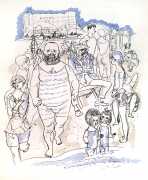

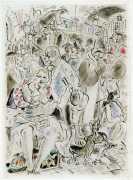

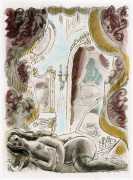

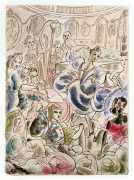

At twenty-one Laborde chose to become a French citizen, and when the First World War broke out he volunteered for the army; his war ended after a gas attack in the spring of 1917. When the war ended Laborde continued to work for satirical magazines. Contributing to Le Rire Rouge and La Baïonnette, his speciality was drawing the prostitutes and brothels of Montmartre. ‘L’amie des filles’ as Carco called him, Laborde often went out of his way to help these young women, acting as witness in their defence in court, lending them money and paying their debts. When Bofa established Le Salon de l’Araignée (The Spider’s Parlour) in 1920 to support graphic artists who had fought in the war, he arranged for Laborde’s drawings to be exhibited, and the newly-established publishing house La Banderole opened the door to book illustration. In 1921 he was commissioned to illustrate Le Chat Maigre (The Scrawny Cat) by Anatole France, who had just been awarded the Nobel Prize.

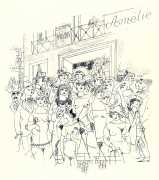

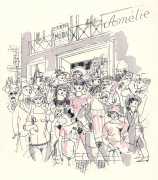

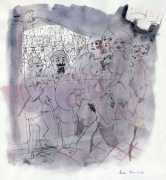

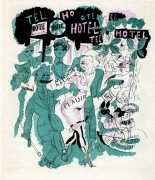

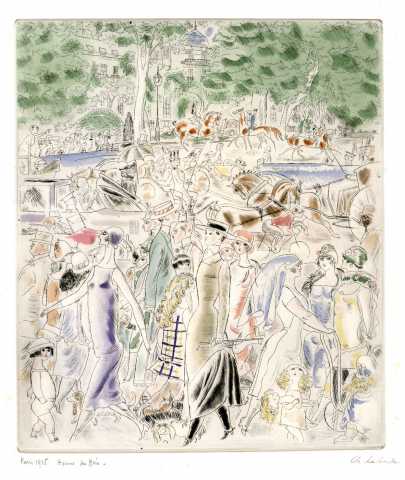

By 1923, when La Renaissance du Livre, under the art direction of Mac Orlan, commissioned Laborde to illustrate L’inflation sentimentale, Laborde was firmly established as an illustrator. By 1930 he had illustrated more than thirty books, including Paris Street Scenes (1926), London Street Scenes (1928) and Berlin Street Scenes (1930), capturing both the beautiful and the ugly, the chaste and the vulgar, the humorous and the ominous.

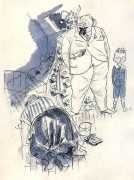

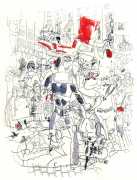

In 1930 Laborde’s close artist friend Jules Pascin committed suicide, which had a profound effect on him. He spent more time travelling, including visits to Moscow, and to Madrid at the height of Franco’s putsch. The magazine Candide commissioned him to draw cartoons of Hitler and Mussolini lauding the triumph of war and death. The travelling and experiences of Europe on the cusp of renewed fighting took their toll on his already failing health; his lungs had never fully recovered from being gassed, and he died from pneumonia in relative poverty and obscurity at the height of the German occupation of his beloved Paris.

Author and art historian Emmanuel Pollaud-Dulian has created a wonderful resource of everything relating to Laborde and his world at the Chas Laborde website which you can find here. Emmanuel Pollaud-Dulian has also written the standard illustrated history of the Salon d’Araignée, Le Salon d’Araignée 1920–1930, with biographies of all the artists associated with Gus Bofa in those formative years, together with many colour examples of their work. It is of course in French, but even if you cannot read the text the pictures are inspiring.