The talented German Jewish artist and cartoonist Erich Godal (his family name was Goldbaum; he chose Godal in his early twenties to avoid being identified solely as Jewish) attended high school in Berlin, and studied painting, set design and sculpture at the Kunstgewerbeschule Berlin-Charlottenburg (Berlin-Charlottenburg School of Applied Arts) under Rudolf Albert Becker-Heyer, Harold Bengen, Teo Otto and Ernst Stern.

The talented German Jewish artist and cartoonist Erich Godal (his family name was Goldbaum; he chose Godal in his early twenties to avoid being identified solely as Jewish) attended high school in Berlin, and studied painting, set design and sculpture at the Kunstgewerbeschule Berlin-Charlottenburg (Berlin-Charlottenburg School of Applied Arts) under Rudolf Albert Becker-Heyer, Harold Bengen, Teo Otto and Ernst Stern.

Godal began his artistic career in 1919 as a poster draftsman for the journal Der Orchideengarten, going on to work for Berliner 8 Uhr-Abendblatt and Simplicissimus. Identifying as a political radical, in 1920 he published the important Revolution portfolio for the Berlin-based Genossenschaft für proletarische Kunst (Cooperative for Proletarian Art).

Godal began his artistic career in 1919 as a poster draftsman for the journal Der Orchideengarten, going on to work for Berliner 8 Uhr-Abendblatt and Simplicissimus. Identifying as a political radical, in 1920 he published the important Revolution portfolio for the Berlin-based Genossenschaft für proletarische Kunst (Cooperative for Proletarian Art).

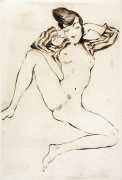

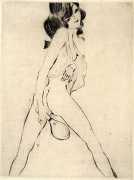

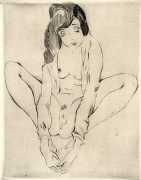

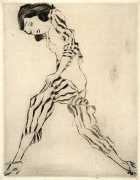

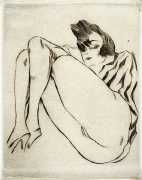

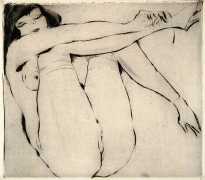

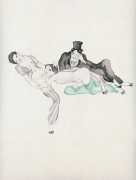

Erich Godal was also involved in the film industry; he worked with director Max Reinhardt on the set design for films including Zwei schwarze Laternen (Two Black Lanterns) in 1921 and Adolf Abter’s Elixiere des Teufels (Elixirs of the Devil) in 1922. In 1927 he created illustrations for Eugen Szatmari’s Berlin volume of Was nicht im Baedeker steht (What is not in Baedeker). Godal was good friends with the composer Werner Richard Heymann and the writer Walter Mehring. It was during the early 1920s that he was regularly drawing and painting erotic art, a reflection of his active social life enjoying the freedom of Weimar Berlin.

After the handover of power to the National Socialists in February 1933, he fled to Prague, where he drew for various émigré magazines including Prager Mittag, Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung, and Simpl. In 1935 he emigrated to New York, and founded the exile newspaper Star with Franz Höllering, provided political cartoons for the short-lived Ken, and worked on the Jewish exile newspaper Aufbau. He was given a teaching position at the New School of Social Research, and illustrated several children’s books by author Roselle Ross. Because of McCarthyism he returned to Germany in 1954 and wrote for the Springer Press publications Welt am Sonntag, Hamburger Abendblatt and Illustrierte Constanze. His autobiography Kein Talent zum Tellerwäscher (No Talent for Washing Dishes) was published posthumously.

Erich Godal’s banker father died in 1934; what happened to his mother Anna in 1939 was to haunt Erich for the rest of his life.

In early 1939 Godal’s mother, 64-year-old Anna Marien-Goldbaum, secured a visa to live temporarily in Cuba while on a waiting list to be admitted to the United States to join her son. The ship on which she sailed, the St Louis, was turned away from Cuba and hovered for three days off the coast of Florida, hoping to be granted haven by President Franklin Roosevelt. On 6 June the New York Daily Mirror published two letters ‘from an aged mother on the wandering steamship to her son, an artist, in New York’.

‘It is so strange how near, and yet how much cut off we really are,’ Anna Goldbaum wrote in one of the letters. ‘I feel that you are supporting me from far away, and that gives me courage to go on.’ In the second letter she tried to put on a brave face: ‘I still have the hope that President Roosevelt and other influential people will help us. I shall not lose courage until the happy end is reached.’ On the day Anna Goldbaum’s letters appeared in the newspaper, the St Louis, denied permission to land in America, headed back to Europe.

The governments of England, France, Holland and Belgium each agreed to admit some of the passengers, and Anna Goldbaum was among those admitted to Belgium. Less than a year later, however, the Germans occupied Belgium. Close to half of the country’s Jewish residents, including Godal’s mother, were deported to Auschwitz, where she perished.

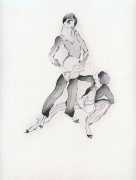

In October 1943 Godal drew the most explicitly critical cartoon about the Roosevelt administration’s policy toward European Jewry ever to appear in an American newspaper. It depicts two State Department bureaucrats callously ignoring a report about the monthly murder of 100,000 Polish Jews.

In October 1943 Godal drew the most explicitly critical cartoon about the Roosevelt administration’s policy toward European Jewry ever to appear in an American newspaper. It depicts two State Department bureaucrats callously ignoring a report about the monthly murder of 100,000 Polish Jews.