Frank Thorne was one of American comics’ finer craftsmen and more notorious personalities. A cartoonist’s cartoonist whose career covers much of the comics medium’s mid-century history, Thorne’s bibliography runs the gamut from sober family-friendly newspaper strips to transgressive hardcore, all delineated with the steady hand of a master illustrator.

Frank Thorne was one of American comics’ finer craftsmen and more notorious personalities. A cartoonist’s cartoonist whose career covers much of the comics medium’s mid-century history, Thorne’s bibliography runs the gamut from sober family-friendly newspaper strips to transgressive hardcore, all delineated with the steady hand of a master illustrator.

Born into a working-class family in Rahway, New Jersey, the youthful Thorne harboured an irrepressible creative urge, touring both as a jazz trumpeter and a stage magician. Cartooning was also deep in his bones, spurred by a childhood love of Alex Raymond, whose feathering inkwork and fetishistic treatment of pulp storytelling tropes in Flash Gordon would be a career-long influence. Breaking into the comics profession when he was just seventeen with a scattering of romance and superhero strips for publishers like Standard and Fawcett, Thorne had inchoate careers in comics and music going well before he graduated from Manhattan’s Art Career School. In the post-WWII era of Thorne’s maturity and marriage to wife Marilyn, cartooning provided the steadiest source of employment available to the young jack of all trades, and with the diligence of a family man Thorne devoted himself to the comic book field.

By 1952 Thorne had landed the holy grail of comics jobs, a syndicated newspaper strip, King Features’ daily Perry Mason. It was well earned – the young Thorne’s work was unostentatious but rock solid, with grounded figure work and an instinctive balance of black and white space, as similar to Roy Crane’s minimal action cartooning as Alex Raymond’s fanciful phantasmagorias. Thorne’s early work compares well to contemporaneous comics by Alex Toth, with crisp lines and a streamlined sense of design giving his strips the ability to build up momentum in a couple of panels. But the constant grind of producing a strip a day and a colour page on Sunday wore heavily on Thorne, and after a few years he regarded King’s cancellation of Perry Mason as a blessing. He went back into comic books, finding steady employment on action strips at Dell – Flash Gordon, Green Hornet, and adaptations of Tom Sawyer, Moby Dick, and the like. The Perry Mason experience had given Thorne a clear leg up – unusually for a commercial cartoonist of his era he pencilled, inked, lettered and coloured most of his jobs, allowing total control over the visual character of his work.

Thorne had by this time built up the desire to script a work of his own creation, but such opportunities were rare in the early sixties, and scripts from others were plentiful enough to allow his growing family a comfortable life. Still, Thorne was developing into a singular talent, and his chance came at DC Comics, losing ground to Marvel but still the industry’s top publisher. Thorne’s style had grown more rendered and rough-hewn as he moved away from newspaper strips, and he settled in with writer Bob Kanigher for the Revolutionary War adventures of frontier ranger Tomahawk.

A 1976 move to Marvel gave Thorne’s career another signature moment, the Conan the Barbarian spin-off Red Sonja, drawn by Thorne with a perfect balance of cartoon realism, gothic shadow, and bawdy humour. Red Sonja soon attracted a fanatical cult audience, and Thorne embraced the culture of fandom at the dawn of the age of comics conventions, doing more than perhaps any other comics creator to establish cosplay as a cultural force.

A 1976 move to Marvel gave Thorne’s career another signature moment, the Conan the Barbarian spin-off Red Sonja, drawn by Thorne with a perfect balance of cartoon realism, gothic shadow, and bawdy humour. Red Sonja soon attracted a fanatical cult audience, and Thorne embraced the culture of fandom at the dawn of the age of comics conventions, doing more than perhaps any other comics creator to establish cosplay as a cultural force.

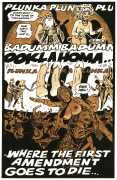

After Sonja, having found a pleasurable and lucrative aesthetic niche, Thorne created more risqué heroines in the Red Sonja mould, but free of Marvel’s content restrictions. Heavy Metal featured sexy spacegirl Lann, National Lampoon carried pneumatic trail guide Danger Rangerette, Playboy ran the Li’l Abner spoof Moonshine McJugs, and in 1985 he published Ghita of Alizarr, a barbarian warrior whose blonde tresses were all that kept her from being a carbon copy of Sonja. And finally, in the 1990s, came The Iron Devil and The Devil’s Angel, Thorne’s most extreme imaginings. Finally free of commercial necessities, they mark the zenith of a talented artist exploring the deepest recesses of the warped American cultural psyche.

Though it always carried a noxious whiff of objectification and outmoded gender typing, Thorne’s erotica was largely good-humoured, with cute and naïve characters desperate for pleasure, and usually finding the happy endings they were looking for amidst genre tropes made softly farcical.