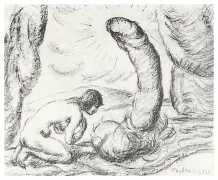

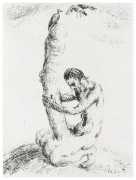

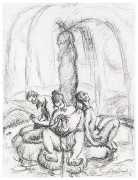

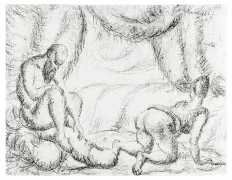

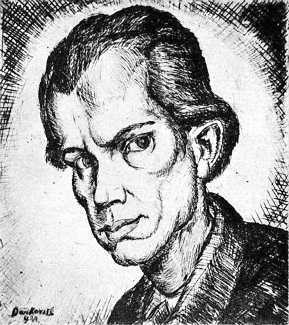

‘I want to rid my art of all illusion,’ wrote the idealistic young Hungarian artist Gyula Derkovits in 1927, ‘because I believe that powerful art can only be created if we show the phenomena of real life, and thus express ourselves more intensely along the way. Both as a human being and as an artist, I feel obliged to express the details of our lives and society without leaving out anything important.’

‘I want to rid my art of all illusion,’ wrote the idealistic young Hungarian artist Gyula Derkovits in 1927, ‘because I believe that powerful art can only be created if we show the phenomena of real life, and thus express ourselves more intensely along the way. Both as a human being and as an artist, I feel obliged to express the details of our lives and society without leaving out anything important.’

Derkovits grew up in Szombathely in the west of the country near the Austrian border. His father was a master carpenter, and despite showing some early artistic talent he was forced to pursue the same trade. A friend who was a sign-painter gave him his first drawing lessons, but in order to get away from his family he volunteered to serve in World War I. It was an unfortunate decision, as he was wounded at the front, leaving him with a paralysed left hand and a lung problem, which developed into tuberculosis. In 1916 he moved to Budapest where he supported himself with a disability pension. In 1918 he joined the Hungarian Communist Party.

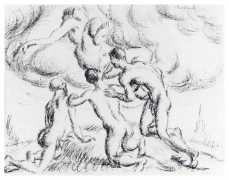

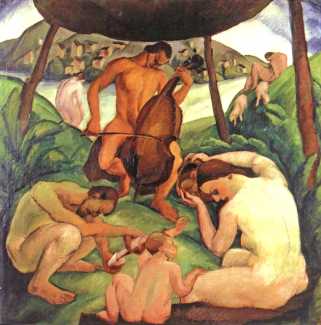

In the evenings he studied drawing and painting at School of Industrial Drawing and the Podolini-Volkmann and Sándor Teplánszky Free Schools. One of the models, Viktória Dombai, was to become his wife three years later in 1921. His break came in late 1918, when leading Hungarian painter Károly Kernstok agreed to take him as a student, free of charge, at the Nyergesújfalu art colony, where he learned etching as well as developing his painting.

The 1920s were uncertain times in Hungary, but Derkovits’ first exhibition in November 1923 was well-received. After two years in Vienna from 1923 to 1925, Gyula and Viktória returned to Budapest. In the spring of 1926 the third exhibition of the New Society of Fine Artists brought him domestic success, and by September 1927 he was represented in the group exhibition of the Ernst Museum with 41 works. In addition to the pictures painted in Vienna, his recent works made in Hungary were also included in the exhibition. Unfortunately the success of the exhibition at the Ernst Museum did not bring financial reward, so in 1928 he established the Hungarian Etching Workshop to teach the technique to other artists.

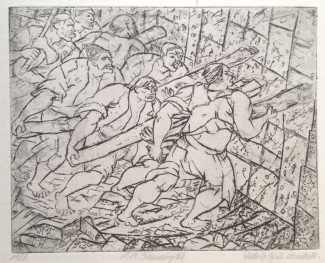

Derkovits was an active supporter of communism, and in September 1930 he took part in a left-wing workers’ demonstration. In a series of etchings titled ‘Dózsa’ (literally ‘dog’, but here in the sense of a dangerous guard-dog), he captured the sufferings of workers throughout Hungarian history. Gyula and Viktória’s last four years together before his early death at just forty were not easy. Struggling with financial problems, the couple had accumulated considerable rent arrears, and though he was happy selling artworks Derkovits refused to accept donations, which he saw as humiliating. In August 1931 the couple was evicted, and they moved in with Viktória’s brother.

Although newspapers praised his works with positive reviews, he only sold very few paintings; Gyula even tried making money as a model like his wife. In February 1933 the Pál Merse Society awarded him the Landscape Painting Prize for his painting ‘Along the Railway’, and a small award ‘for prestigious moral success’ alleviated the couple’s financial worries. Although some of his best-known paintings, like ‘The Bridge Builders’, date from his final year, his contribution to Hungarian art was only truly recognised after his death.

In 2019 the Courtauld Institute of Art in London published a landmark study A Reader in East-Central-European Modernism 1918–1956, Chapter 15 of which looks at Gyula Derkovits’ place in Hungarian art, and how his work relates to Hungarian photography in the 1920s and 30s. You can read the chapter here.