Jindřich Štyrský was born in Dolní Čermná, a small town in the hills near the Czech border with Poland, where he spent his childhood. The loss of his half-sister from heart disease in 1905 significantly influenced his life and later artistic work. He studied first at the grammar school in Hradec Králové, then at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, and from the beginning was active in the art world – from 1923 he was an active member of Devětsil, an association of Czech avant-garde artists which had been founded in Prague in 1920, and from 1932 to 1942 he was a member of the Mánes Association of Fine Artists.

Jindřich Štyrský was born in Dolní Čermná, a small town in the hills near the Czech border with Poland, where he spent his childhood. The loss of his half-sister from heart disease in 1905 significantly influenced his life and later artistic work. He studied first at the grammar school in Hradec Králové, then at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, and from the beginning was active in the art world – from 1923 he was an active member of Devětsil, an association of Czech avant-garde artists which had been founded in Prague in 1920, and from 1932 to 1942 he was a member of the Mánes Association of Fine Artists.

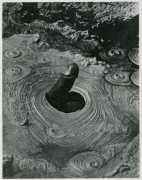

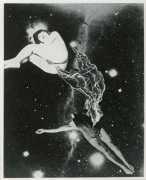

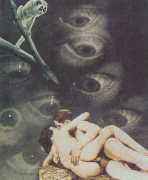

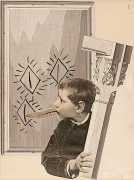

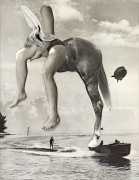

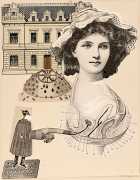

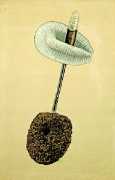

His early works were partly influenced by cubism, but surrealism later became his main inspiration and style. During the summer of 1922, he met fellow painter Toyen (her given name was Marie Čermínová; you can read more about her here), and they worked closely together as well as having a close intimate relationship. From 1925 to 1928 they lived in Paris, where Štyrský developed his interest in painting and his early love of photography, and he and Toyen started to call their style ‘artificialism’, an artistic link between poetics and surrealism, reality and abstraction.

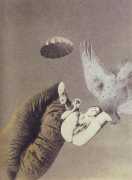

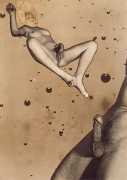

After they returned to Prague, Štyrský became chief set designer at the Osvobozené Divadlo (Liberated Theatre), and in 1934, together with Toyen, Bohuslav Brouk, Vítězslav Nezval and Karel Teige, he became a co-founder of the Skupina Surrealistů v ČSR (Group of Surrealists in Czechoslovakia). He was also the main founder member of the editorial group which produced the provocative and groundbreaking Erotická Revue (Erotic Review), and editor of the radical publishing house Edice 69, which among other things published his erotic photo-montage-accompanied essay Emilie Přichází ke Mně ve Snu (Emilie Comes to Me in Dreams).

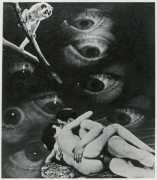

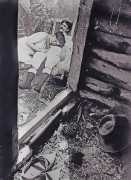

At the invitation of the Parisian surrealists, Štyrský and Toyen returned to Paris in 1935, where Štyrský exhibited his photographs in two well-received collections, Muž s Klapkami na Očích (The Man with the Blindfold) and Žabí Muž (The Frog Man). By now his work was seen as a significant contribution of surrealism to modern photography. Unfortunately Štyrský fell seriously ill during the time in Paris, probably from the same heart disease as his sister. He only recovered temporarily from it during his stay. However, he kept up a prodigious flow of work, explaining that ‘My eyes constantly need to be fed. They swallow things greedily and raw, and at night they digest it in their sleep,’ thus capturing his constant need to create.

Štyrský died in Prague, just three years after his second return from Paris; his surrealist grave in the Strašnice Cemetery was designed by Toyen.

There are many reasons why Jindřich Štyrský still attracts attention, unlike many of his peers who have disappeared from art history. He was one of the great experimenters, in his art, his range of media, and his personal life. As art historian Karel Srp has written, ‘Štyrský’s work is so multifaceted that it seems to be incomprehensible as a whole: we always perceive only one part, the when we examine it another appears, and suddenly what we thought we knew appears in new, altered contexts. One facet reflects another, and as soon as we are convinced that we can already see inside the crystal, we become uncertain; it could only have been a reflection of one aspect of Štyrský’s imagination.’