Joan Semmel, who has been painting naked bodies for more than half a century, is best known for her large hyper-realistic works which still shock many viewers. Her focus has brought her into conflict with historic messages about women’s sexual passivity and women’s value as a seductive lure. As she explains, ‘Women are essentially a chattel in so much of the history of western art, and that’s what I have always rebelled against.’

Joan Semmel, who has been painting naked bodies for more than half a century, is best known for her large hyper-realistic works which still shock many viewers. Her focus has brought her into conflict with historic messages about women’s sexual passivity and women’s value as a seductive lure. As she explains, ‘Women are essentially a chattel in so much of the history of western art, and that’s what I have always rebelled against.’

Semmel first studied art at Cooper Union in New York, and was married and a new mother when in 1957 she spent six months in the hospital because of tuberculosis. After recovering she enrolled at the Pratt Institute and received her Bachelor of Fine Art. She followed her husband to Spain, but they separated after their second child was born – they were not allowed to divorce because divorce was not legal in Spain at that time. Moreover, a woman on her own was not allowed to rent an apartment unless there was a husband or a father on the lease. This began her personal dissatisfactions with political structures.

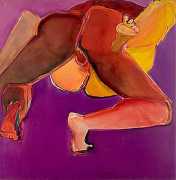

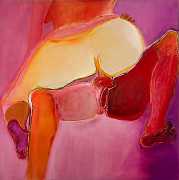

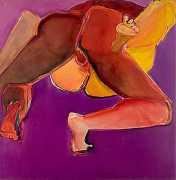

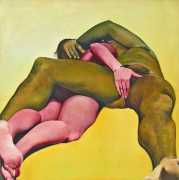

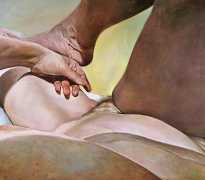

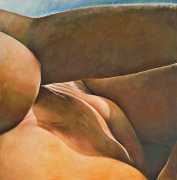

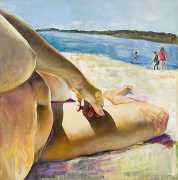

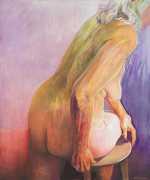

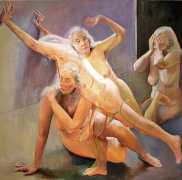

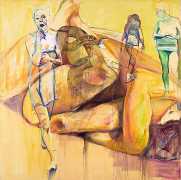

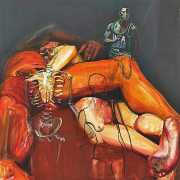

For the next eight years in Spain she painted in an abstract expressionist style, but felt sidelined in the genre since abstraction was the style of privileged white men. In 1970 she returned to New York and started working on her ‘sex paintings’, large-scale oils of people having sex. While their bodies were realistically rendered, they were painted in vivid colours of red, purple, yellow and green. Her 1972 ‘erotic series’ featured models sharing sex in her studio. Again the sexual scenes were realistic, but the unreal hues served as a reminder of her early years of painting abstract art.

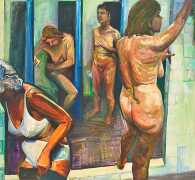

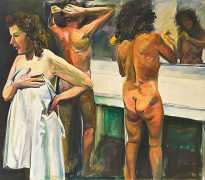

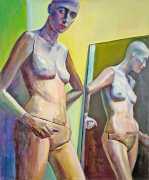

Starting in the 1980s she stopped painting men and started using herself as a model, reinventing her own naked body as she aged. She made a series of paintings in locker rooms and gymnasiums where people were looking at themselves in mirrors, and took pictures of herself in the mirror holding her camera. Years later she used drawings from the locker room series and superimposed them over earlier sex paintings, layering one image over the other. The figures seem to be in motion as if they are moving through time.

In October 2022 Ewa Giezek interviewed Joan Semmel for the Aware Women Artists online magazine. You can read the whole interview here; we have chosen just a few of the questions and Joan’s replies.

Going back to the beginning of your figurative work in the early 1970s, at that time you were shocked by the sexualised images of women in American visual culture. How did this shock translate into being the starting point for your erotic paintings?

My understanding of my role as a woman and as an artist became much clearer to me during that period, because of my inability to enter the New York art world easily. I was already a feminist, but I realised that there were other people with whom I could talk about my concerns. I joined groups like the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee, where Lucy Lippard was very influential. I was linked to other artists and I went to their studios; we all influenced each other during our meetings. As a young woman at that time, my feeling was that the problems began in the bedroom and needed to be addressed from this source. I felt that until a woman could have her own sense of her own sexuality and desire, she would never be an active member in the political structure. Pornography was so prevalent at that time. It was advertised as a sexual revolution, but it was a sexual revolution for men and not for women.

Were your erotic paintings a way of creating more space for the women’s sexual freedom and expression?

I was interested in breaking down the prejudice in which sexuality was shameful for women, that good women didn’t feel sexual desire. I started to wonder why women didn’t try to respond to the pornography made for men. I wanted to show relationships where women and men had equal needs and desires. At that time here was no concept of the ‘female gaze’ – I wanted to reflect in my paintings that the person making these works of art was a woman, and that it was through her eyes that the work must be seen.

You organised your first erotic paintings exhibition by yourself, renting the space and mounting the show. Then in 1975 your work was part of an exhibition banned by the Supreme Court due to the show’s explicit male nudity. 43 years later in 2018, you were a part of an exhibition called In the Cut: The Male Body in Feminist Art at the Stadtgalerie Saarbrücken in Germany. Does this speak to an evolution in the way erotic works are now recognised in the art world?

Censorship still exists. The United States comes from a puritan background where anything sexual is still suspicious. There have been feminist exhibitions in galleries, but I have even been censored in those groups. In the Cut is a much later show, and honestly I think it was too centred on the male body. I wasn’t interested in the idea of doing to male bodies what male artists have done to women’s bodies. I don’t see the point of reversing abuse. For me eroticism has to be to do with an interchange and sensitivity of touch, of sound and intellect.

We are very grateful to our Russian friend Yuri for suggesting the inclusion of this artist, and for supplying most of the images.