Lisa Yuskavage is an American painter known for her provocative, psychologically charged figurative work which blends high art tradition with pop-cultural aesthetics. She rose to prominence in the 1990s with paintings reimagining the naked female body through a distinctive blend of accomplished technique, eroticism, and emotional complexity. Her work challenges and complicates perceptions of sexuality, femininity, and the all-too-often male gaze in contemporary art.

Lisa Yuskavage is an American painter known for her provocative, psychologically charged figurative work which blends high art tradition with pop-cultural aesthetics. She rose to prominence in the 1990s with paintings reimagining the naked female body through a distinctive blend of accomplished technique, eroticism, and emotional complexity. Her work challenges and complicates perceptions of sexuality, femininity, and the all-too-often male gaze in contemporary art.

Yuskavage grew up in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and studied at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University, earning her Bachelor of Fine Art in 1984. She then attended the Yale School of Art, where she completed her Masters in 1986. At Yale she was exposed to rigorous formal training and the intellectual currents of postmodern theory, but at a time when conceptual and minimalist approaches dominated the art world her insistence on figurative work was seen as radical, especially as she began incorporating erotic and seemingly kitschy elements into her canvases.

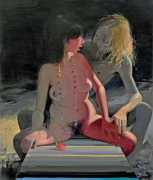

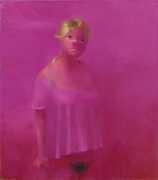

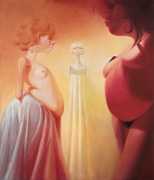

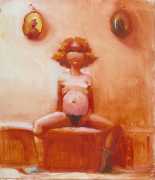

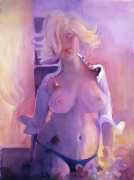

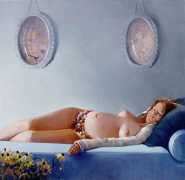

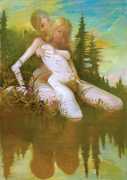

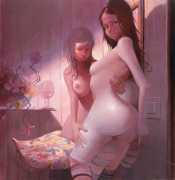

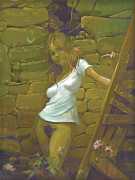

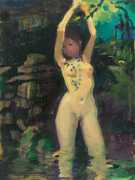

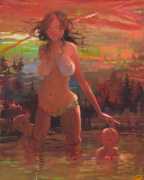

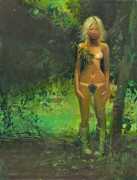

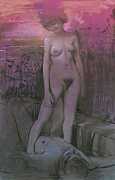

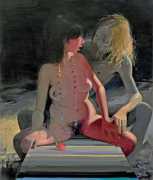

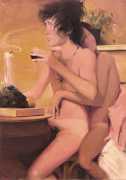

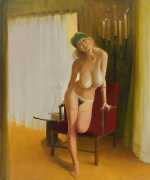

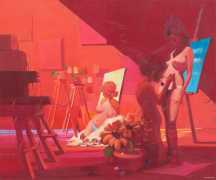

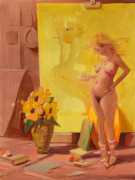

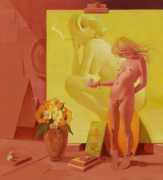

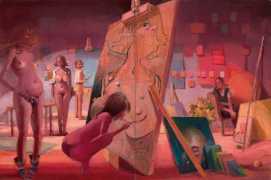

Emerging in the New York art scene in the early 1990s, Yuskavage’s early work focused on female figures with exaggerated proportions and overtly sexual poses. The paintings, often rendered in soft, glowing colour palettes reminiscent of renaissance or rococo painting, juxtapose vulgarity with beauty in a way that drew both acclaim and controversy. Her figures, frequently described as part pin-up, part cherub, are not passive subjects, but confront the viewer with complex emotions ranging from shame and vulnerability to empowerment and defiance.

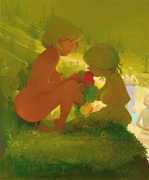

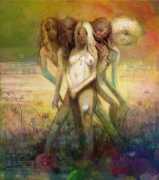

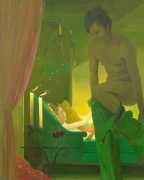

As her career progressed, Yuskavage’s subject matter evolved. While her early paintings often presented solitary female figures in ambiguous interior spaces, her later works expanded into more complex narratives and group compositions. Landscapes, male figures, fantastical settings and surreal motifs began to populate her canvases. Through all these shifts, her work has remained anchored in a deep exploration of human psychology, identity, and the act of seeing.

Lisa Yuskavage has consistently questioned the expectations placed on women artists and the reception of female sexuality in art, pointing out how male artists can depict erotic content without reproach while women are often accused of exploitation or self-exposure. Her paintings deliberately navigate this terrain, asserting a space where female sexuality can be both aesthetic and conceptual, personal and performative.

For the catalogue of a 2016 exhibition of her work at the Contemporary Art Museum in St Louis, Lisa Yuskavage spoke with Katy Siegel, professor of art history and chief curator of the galleries at Hunter College and curator at large at the Rose Art Museum. Here is part of their conversation.

There is a sense of submission and aggression in the viewer’s relationship to your paintings. You’ve spoken about realising you were letting painting be on top, and that you were being submissive to it.

It’s very easy in a studio to get overwhelmed by all the things you could possibly do, or should do, or the things you’re responsible for. You get to a point where you have to be stronger than those noisy currents. It comes down to flipping the dynamic. One of the most effective paintbrushes is one’s wilfulness.

The question of being a woman and how that situates one socially and psychologically is so basic to your work. You’re an enormously abstract thinker for someone who doesn’t want to say that she is a conceptual painter.

I would say more synthetic than conceptual.

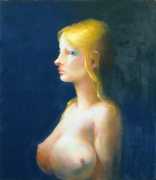

It’s abstract in the sense that it’s structural thinking – seeing the types and categories, rendering them as characters, as archetypes. The women are archetypes, too: blonde, brunette, and redhead.

Yes, but once you understand conventions, you can start playing with them.

What’s unusual about your work is that you developed an interest in the conventions of how things are made.

Understanding pictorial conventions, and then upending them, is quite important to me.

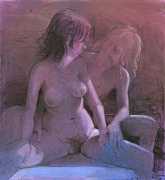

The ability to move back and forth between being the person who’s looking and being the person who’s looked at seems very active in your work.

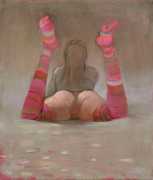

On a YouTube video related to the opening of one of my exhibitions, some troll wrote: ‘Well she clearly’– and I like the word ‘clearly’ in this context – ‘desperately wants to be the women in her paintings, but can’t.’ I remember looking at the chicks in Penthouse as a girl, and thinking, ‘If that’s a woman, then what the fuck am I?’

Going back to the kind of representation you saw when you were young, and figuring out the typology and its conventions, is really important.

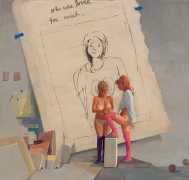

I took the images that had stunned me the most as a kid – or stung me the most, or made me hot in the face. I decided to create my own images based on those pictures, and pose my own models.

But it wasn’t just any model; it was the model, ‘model’ in the sense of being the original, the most essential.

Yes. That’s when I thought that if I was going to work from a live model, it should be Kathy, one of my first childhood friends. She was the foxiest girl in school and a cheerleader, a seemingly light-hearted person who was actually extremely complex. I was the dorky studious one, as a type – I would help with school work and she would help procure the boys. A perfect gal pal symbiosis. Years later, I thought that if I was going to have a living person pose for me, it would have to be someone profoundly integral to my imagination. Every part of her image was very loaded as material for me.

She doesn’t feel inert in those paintings. She feels powerful, potent – as if she’s collaborating.

Well, yes. It takes a lot of psychological strength to lift something out of the gutter, These may be dumb ideas until they’re not.

Lisa Yuskavage’s website, where you can see more of her art, together with videos and the background to her work, can be found here.