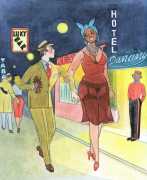

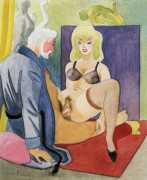

Marcel Vidoudez is one of those illustrators who superficially led a conventional life, illustrating children’s books and religious texts and designing posters for august organisations, but who also had an important and lucrative sideline in erotic watercolours for select clients.

Marcel Vidoudez is one of those illustrators who superficially led a conventional life, illustrating children’s books and religious texts and designing posters for august organisations, but who also had an important and lucrative sideline in erotic watercolours for select clients.

Vidoudez grew up in the French-speaking Swiss town of Bex, son of a secretary of the union of Swiss chocolate makers. After leaving school he studied first at the École de Dessin et d’Arts Appliqués (School of Drawing and Applied Arts) in Lausanne, then at the École des Beaux-arts (School of Fine Arts) in Paris. He married in 1933 and settled in Saint-Saphorin on the north coast of Lake Geneva; their daughter Nicole was born in 1939.

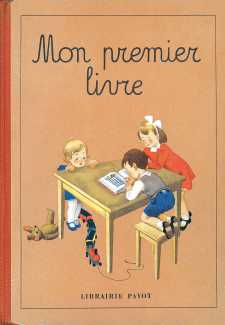

During the 1940s and 50s Marcel Vidoudez produced illustrations for a range of children’s books, mostly for the Lausanne publishers Librairie Payot and Éditions Novos; his best-known is probably the primary reader Mon premier livre (My First Book, Payot, 1949), which you can see in full here. Other children’s books included Rondes et chansons (Rounds and Songs, Payot, 1944), Petites histoires de bêtes (Little Tales about Animals, Novos, 1945), Jésus (Payot, 1950), Visite au zoo (Novos, 1954), and Notre pain quotidian (Our Daily Bread, Novos, 1960).

During the 1940s and 50s Marcel Vidoudez produced illustrations for a range of children’s books, mostly for the Lausanne publishers Librairie Payot and Éditions Novos; his best-known is probably the primary reader Mon premier livre (My First Book, Payot, 1949), which you can see in full here. Other children’s books included Rondes et chansons (Rounds and Songs, Payot, 1944), Petites histoires de bêtes (Little Tales about Animals, Novos, 1945), Jésus (Payot, 1950), Visite au zoo (Novos, 1954), and Notre pain quotidian (Our Daily Bread, Novos, 1960).

It was around 1945 that Vidoudez made the acquaintance of the chansonnier, poet and humourist Jean Villard-Gilles and the illustrator and cartoonist Géa Augsbourg (the pseudonym of Georges-Charles Augsburger), and the three became the centre of a free-thinking group of artists; it is no coincidence that Vidoudez separated from his wife in 1951, then lived a more urban life in Bern and Lausanne before moving to Hermance, a lakeside suburb of Geneva, in 1964. It is also in keeping that he died while partaking of an extended meal with wine at a restaurant in February 1968.

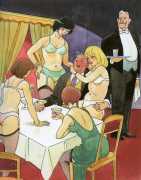

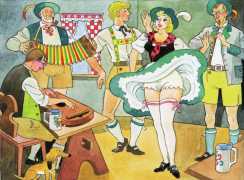

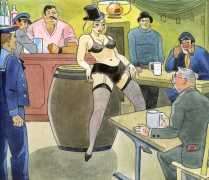

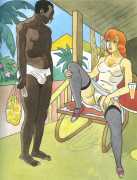

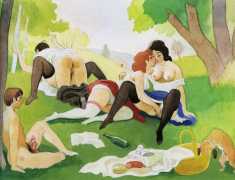

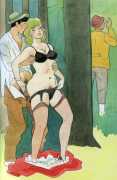

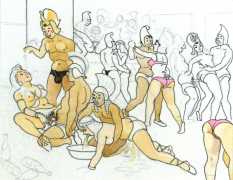

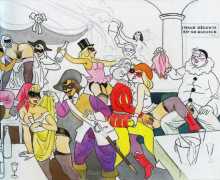

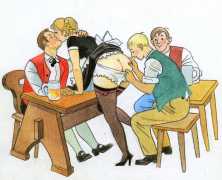

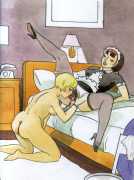

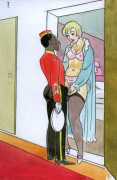

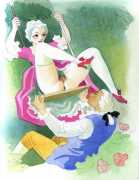

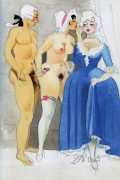

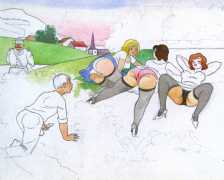

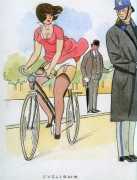

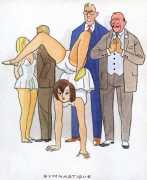

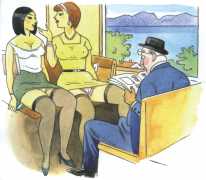

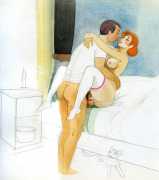

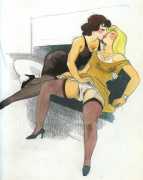

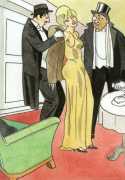

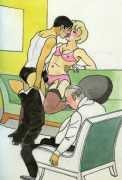

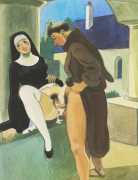

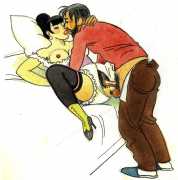

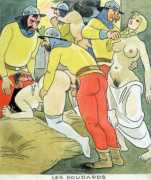

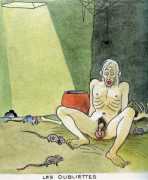

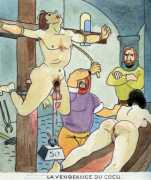

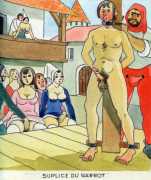

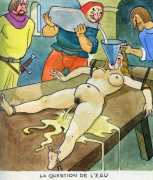

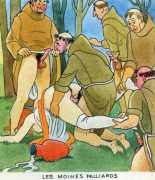

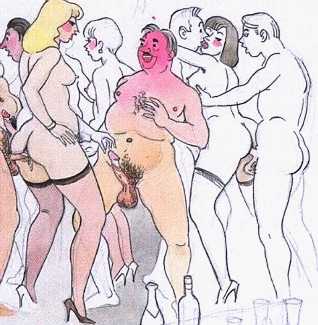

What few people knew about Vidoudez was that for most of his artistic career he had a second string to his output, a pressure valve for his creativity and imagination and quite possibly a useful source of income. He painted watercolours of his fellow Swiss getting drunk, having sex, frolicking semi-clothed in the countryside – and tellingly often getting very excited about peeks of the forbidden, from frilly knickers to barging in on lesbian encounters. Four hundred of these small paintings were found by his daughter after he died, and we can only guess how many others were sold ‘under the counter’ in Lausanne directly from Vidoudez’s briefcase.

It was Nicole Vidoudez’ relation, the Geneva luthier Pierre Vidoudez, who encouraged her to make Marcel’s erotic work more widely known; the Lausanne Galerie HumuS mounted an exhibition in April 1996, and in 2013 published Marcel Vidoudez, dessinateur érotique (Marcel Vidoudez, Erotic Illustrator), with many reproductions of his work and introductions by Michel Froidevaux and Pierre Yves Lador.

It was Nicole Vidoudez’ relation, the Geneva luthier Pierre Vidoudez, who encouraged her to make Marcel’s erotic work more widely known; the Lausanne Galerie HumuS mounted an exhibition in April 1996, and in 2013 published Marcel Vidoudez, dessinateur érotique (Marcel Vidoudez, Erotic Illustrator), with many reproductions of his work and introductions by Michel Froidevaux and Pierre Yves Lador.

As art historian Michel Froidevaux writes in the introduction to Marcel Vidoudez, dessinateur érotique, ‘In French-speaking Switzerland in the middle of the twentieth century we did not joke about love, which had to be confined to the family, to procreation within marriage, consecrated by the state and by the church. Protestantism, corseted by Calvinist Puritanism, and Catholicism, obsessed with original sin, would not have tolerated the public expression of the pleasure of the senses. For an illustrator like Marcel Vidoudez, a regular contributor to children’s publications and illustrator of episodes from the life of Jesus, there was no question of showing his erotic watercolours publicly. He would very soon have stopped receiving commissions for primers like Mon premier livre or orders from the Missionary Department to promote Christian evangelism in Africa.’