The artist Paul-Marc-Joseph Chenavard, judging by the fragmentary descriptions of his character which are available, was a most unusual man. He exhibited so little that he was hardly known to the public, and to the majority of Parisian artists, but Delacroix, Baudelaire, Charles Blanc, Gautier, Théophilc Silvestre, and later Courbet counted him as a friend, taking keen pleasure in his conversation. He possessed an immense fund of information backed by a memory so perfect that he quoted continually from a wide variety of sources. Imaginative, pessimistic, quixotic, he was the source of an endless sequence of unusual ideas which delighted and entertained his intimates. Baudelaire wrote that there was no one with whom Delacroix loved so much to talk, in spite of the fact that the two were seldom, if ever, in agreement.

The artist Paul-Marc-Joseph Chenavard, judging by the fragmentary descriptions of his character which are available, was a most unusual man. He exhibited so little that he was hardly known to the public, and to the majority of Parisian artists, but Delacroix, Baudelaire, Charles Blanc, Gautier, Théophilc Silvestre, and later Courbet counted him as a friend, taking keen pleasure in his conversation. He possessed an immense fund of information backed by a memory so perfect that he quoted continually from a wide variety of sources. Imaginative, pessimistic, quixotic, he was the source of an endless sequence of unusual ideas which delighted and entertained his intimates. Baudelaire wrote that there was no one with whom Delacroix loved so much to talk, in spite of the fact that the two were seldom, if ever, in agreement.

The one project that would have made his work famous never happened. In April 1848 the new French revolutionary government signed a decree awarding the gigantic task of decorating the Pantheon in Paris, the new ‘people’s temple’, to ‘Citizen Chenavard’, the mysterious and almost unknown artist from Lyon, who had contrived a scheme for 62 paintings depicting the development of human knowledge. Thus was begun one of the most bizarre and ill-fated enterprises in the history of western art. Had this panorama of human destiny been installed, it could not thereafter have failed to attract the attention of the learned, while simply mystifying the casual spectator. Instead, its forgotten fragments lie rolled up in the basement of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, while the name of its author can scarcely be found in any of the innumerable histories of nineteenth century French art. Only an accident of history prevented its being placed in its intended location, the accident of the return of the building to the Catholic Church at the time of the coup d’état of 1851. Its substance was far too unorthodox, not to say heretical, for acceptance by the clergy. When in 1885 St Genevieve once more became the Pantheon, Chenavard was too old and angry to take up the task again.

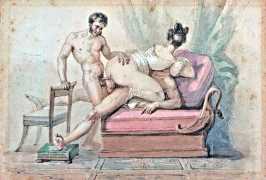

Though a brilliant thinker and conversationalist. Chenavard the painter lacked both motivation (his inherited wealth meant he never had to earn from his art) and originality. As art critic Joseph Sloane writes, ‘His great defect was not plagiarism, nor even a lack of colour sense, but an overwhelming aesthetic dullness.’ At least the series of erotic paintings rediscovered in the 1970s and attributed to Chenavard in 2017 show that his interests included one interest that was not so dull.