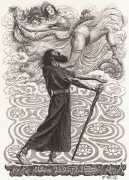

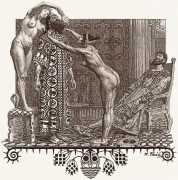

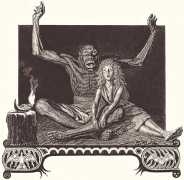

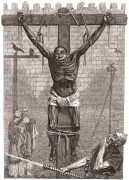

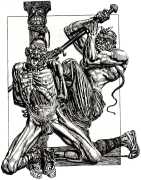

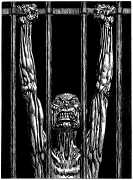

As Alain Leduc wrote in a 2020 article, ‘Almost unclassifiable as an artist, Raphaël Freida uses the eternal vocabulary of oppression, torture and prison, ropes, chains and shackles, hands clenched on the bars of a gate.’ Much of his detailed and masterful work, located in the dark hinterlands of pain and sexuality, reminds us that the human condition, even that of ‘civilised’ democracies, ignores suffering at its peril, including the abominable massacres which have sometimes transformed entire continents into gardens of torture.

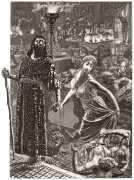

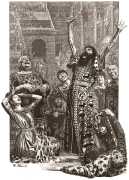

Starting with the facts, Raphaël Freida was a French painter, poster artist, and illustrator, who grew up in Digne in Provence. After studying at the École Nationale des Beaux-arts de Lyon from 1892 to 1899 he settled in Paris, where he was a student of Jean-Paul Laurens. He started work as a cartoonist for Félix Gaudin’s stained glass factory, and worked on many stained glass windows around the world for the next ten years. Gradually he moved into illustration, producing advertising posters for Camis & Cie, and receiving book commissions, starting with a deluxe edition of Leconte de Lisle’s Poèmes barbares for the Paris publisher Romagnol.

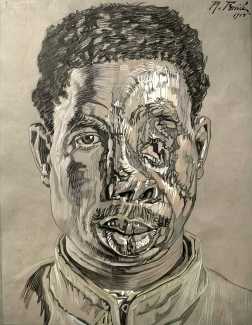

It was his experiences in the First World War that drew Freida towards his dark lithographic work. Though as a nurse at the Centre for Maxillofacial Surgery in Lyon he did not see the carnage first hand, Freida was requested by Dr Albéric Pont to draw facially injured people for a medical portfolio titled Les misères de la guerre (The Miseries of War), poignant portraits of men whose lives had been changed forever through the destruction of warfare.

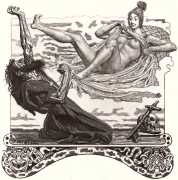

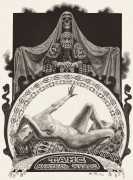

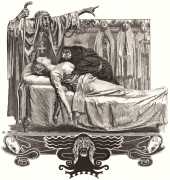

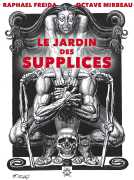

Between 1903 and 1929 Frieda regularly exhibited his works at the Salon of the Société des Artistes Français, winning a gold medal at the International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Nice in 1929. After the war he returned to his illustration work, producing the two portfolios we have included here, Anatole France’s Thaïs in 1924 and Octave Mirbeau’s Le jardin des supplices in 1927.

After 1929 Freida gradually sank into depression; he received no further commissions and stopped exhibiting at the Salon des Artistes. In the winter of 1942, poor and destitute, he developed bronchopneumonia and died in the Broussais Hospital. He was buried in a common grave.