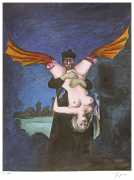

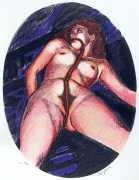

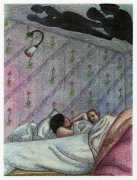

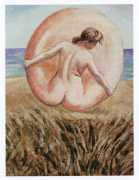

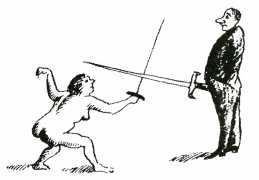

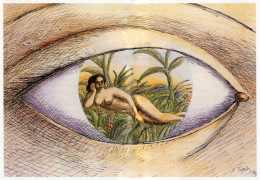

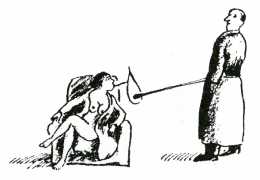

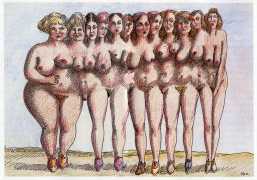

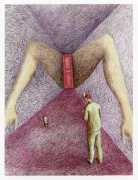

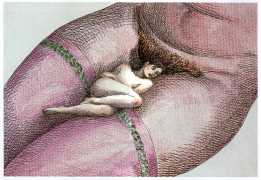

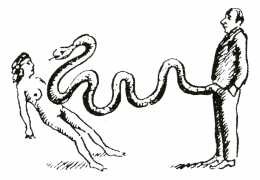

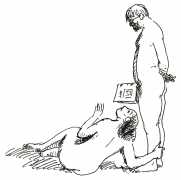

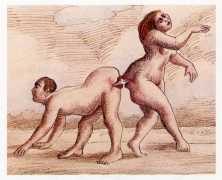

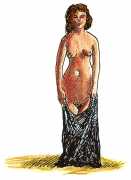

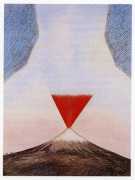

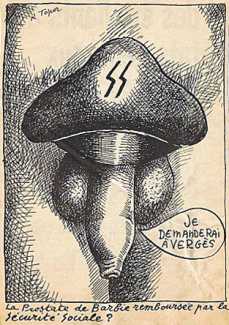

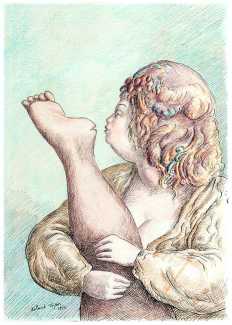

In many ways Roland Topor was the supreme iconoclast. Illustrator, cartoonist, painter, novelist, playwright, screenwriter, filmmaker, actor, he was gifted with both imagination and discipline, and was unafraid to depict life’s darkest absurdities.

In many ways Roland Topor was the supreme iconoclast. Illustrator, cartoonist, painter, novelist, playwright, screenwriter, filmmaker, actor, he was gifted with both imagination and discipline, and was unafraid to depict life’s darkest absurdities.

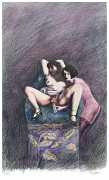

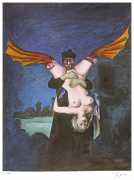

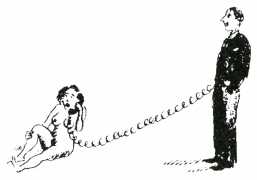

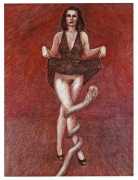

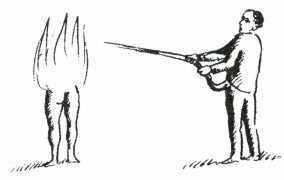

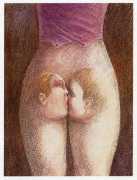

Topor’s narratives are rife with macabre ironies, scatology and cruelty, which sometimes seem intended to shock and reframe human interactions to an insane extent. When his play Joko fête son anniversaire (Joko’s Anniversary) was performed in Brussels in 1972, one critic commented ‘In some countries the author would be shot.’ The 1977 play Vinci avait raison (Vinci was Right) is set in a house where no one can escape, the toilets are clogged, and excrement becomes evident on stage. Critical responses include the suggestion that ‘We must put this idiot in prison for creating such filth’. His work is sometimes classed as post-surrealist horror, portraying bizarre situations in which human realities that are normally unspoken are laid bare in confrontations with – using his own favourite phrase – ‘le sang, la merde et le sexe’ (blood, shit and sex).

Roland Topor’s relationship with the world was coloured by his childhood experience during the Second World War. His parents had moved from Warsaw to France in the 1930s, and in 1941 his father Abram, along with thousands of other Jewish men living in Paris, was required to register with the Vichy authorities. He was subsequently arrested and interned in a prison camp at Pithiviers, where inmates were held before being sent to concentration camps, usually Auschwitz. Of the thousands who were sent to Pithiviers only 159 survived, but Abram managed to escape. While his father was in hiding, the Topor’s Paris landlady unsuccessfully tried to persuade the children, Topor and his older sister Hélène, to divulge the location of their father. Then in May 1941 a neighbour tipped off the Topor family that the French police and the Gestapo were going to search the building, so the family fled to Vichy France. In Savoie, four-year-old Roland was placed in a French family and given a false name. Fortunately all the family survived, and in 1946 they sued the landlady to have their belongings returned and resume living in their former apartment. The court ruled in their favour, they returned, and were once again paying rent to the landlady who had tried to have them apprehended.

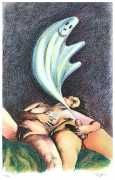

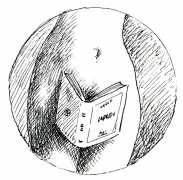

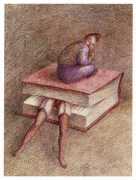

Though a multi-talented creator, we concentrate here on Roland Topor’s graphic works with their surrealist humour. Topor studied art and graphic design at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and his cartoons and illustrations started to appear in the early 1960s in publications including Bizarre and Hara-Kiri. His unique world is full of absurd and impossible situations, yet it is precisely through the juxtapositions that he makes important social and political statements. His artworks have appeared in many books, magazines, newspapers, posters and film animations.

Many of Topor’s graphics can be found online, and have also recently started to appear in print collections, including Le monde selon Topor (The World According to Topor), Les Cahiers Dessinés, 2017, and Chefs d’oeuvre 1 (Masterworks 1), Les Cahiers Dessinés, 2019.