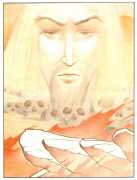

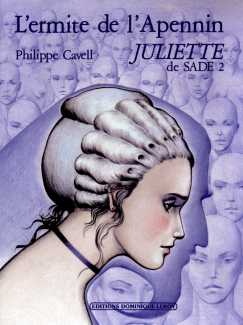

L’ermite de l’Apennin (The Hermit of the Apennines) is the second and last part of the Cavell interpretation of the Marquis de Sade’s famous Juliette, ou les prospérités du vice (Juliette, or the Rewards of Vice). The meeting of Juliette and the ogre Minski holds a very special place in Juliette. The hermit shares the taste for evil of other Sade characters but goes far beyond them – sorcerer, cannibal, recluse, protected by volcanoes, Minski is so frightening that Juliette and Sbrigani are forced to flee to escape him before they in turn become the next meal.

L’ermite de l’Apennin (The Hermit of the Apennines) is the second and last part of the Cavell interpretation of the Marquis de Sade’s famous Juliette, ou les prospérités du vice (Juliette, or the Rewards of Vice). The meeting of Juliette and the ogre Minski holds a very special place in Juliette. The hermit shares the taste for evil of other Sade characters but goes far beyond them – sorcerer, cannibal, recluse, protected by volcanoes, Minski is so frightening that Juliette and Sbrigani are forced to flee to escape him before they in turn become the next meal.

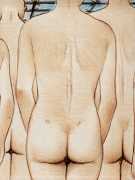

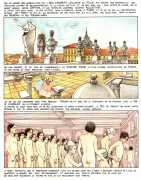

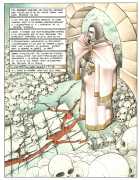

When compared with the first Cavell volume of Juliette, this is an altogether more polished and mature production. The varied composition, the subtle use of colour, show that during his journey as an illustrator he has learned a lot from the masters of the art like Moebius and Crepax. The tale of Juliette and Sbrigani’s encounter with Minski has clearly struck an artistic nerve, and comparisons with Blake and Piranesi are not out of place.

We show here the first half of L’ermite de l’Apennin, up to the point where Juliette is shown Minski’s mausoleum and knows that the window of opportunity to escape is a very short one.

L’ermite de l’Apennine was published by Éditions Dominique Leroy.

In a blog of February 2015, the Australian writer and academic Brogan Bunt has written an excellent analysis of this key episode in Sade’s Juliette, which we recommend towards understanding why Sade included such an unsavoury character as Minski.

Minski’s Hospitality: Hospitality in Socially Engaged Art

To invite somebody in. To permit them to participate. To describe/circumscribe a context for participation.

This is, after all, your artwork. You are named. A group of you are named. The group has a name. People come along. Perhaps they belong. Usually they do. They figure out what they are supposed to do. They do it. Or they don’t quite do it. But whatever they don’t quite do also occurs within the work. It is ultimately yours. You ultimately permit it even if you disapprove because it adds to the work and, as I say, it is ultimately yours.

Apart from questions of ownership and estrangement – appearing on the doorstep and offering a partial, conditional welcome – there is also, however, the underlying sense that hospitality is unnecessary, that nothing like hospitality is happening, that there is no owner and there are no strangers. There is instead the social, which simply has to be activated, which remains a latent force, which art can somehow realise. So at one level all the protocols are suspended – the work of art struggles to occupy a position beyond hospitality, to represent instead the literal foundation of the social. People only have to come and they will see and act socially.

Of course I should have read Derrida on hospitality, but I haven’t. Instead I have read about one hundred pages in the middle of the Marquis De Sade’s Juliette. Juliette, villainous sister of Justine, who profits only from vice, who is doomed if she ever turns her back on vice, who is compelled to obey vice’s law. She is as bound by law as any other. She is as drawn to law as any other.

Anyway, in the middle of her book, after she has fled from France to Italy, after she has learned the art of poisoning, she meets Minski the Monster on the high slopes of a volcano near Florence. Over seven feet tall, with an 18 inch cock – a coprophage and cannibal – Minski would have slaughtered Juliette and her small entourage (Augustine, Zephry, and Sbrigani) if he hadn’t recognised a kindred spirit. Juliette and her travel companions were buggering one another at the lip of the volcano. So Minski is friendly. He recognises his own predilections. He insists they follow him on a long walk to his abode. They descend for several hours into a dark valley, cross a lake in a gondola and pass through several substantial castle walls until they find themselves into low ceilinged room strewn with bones.

Rabelasian in his appetites, Minski is outrageously rich and permanently erect. He has travelled the world, accumulating all its vices. He adheres to Nature, which represents nothing but his own libidinal, murderous urges. He ejaculates at least ten times a night and every creature he fucks dies (and then is eaten). He has torture machines to kill multiple victims with the pull of a single cord. He keeps a massive seraglio of victims, carefully grouped in terms of age and gender. The sick and the not so sick are regularly fed to wild beasts.

He is also, it seems, a philosopher – and he speaks specifically and for several pages about hospitality, about the absurdity of hospitality. This after he has inhospitably murdered Augustine – and Juliette has expressed concern that she may be next. They engage in dialogue, although not strongly Socratic in nature. Minski makes no show of ignorance. The laws of Nature – of enlightened human action – are writ large for him. If the weak are hospitable to the strong it is only in order to survive. If the strong are hospitable to the weak then their strength is compromised. There is no reason to admit strangers. He draws upon a variety of cultural precedents, describing examples of cultures that instantly destroy outsiders. The strong have no obligations to the weak. They are the weak’s calamity. That is how it has always been and that is how it will always be.

Juliette accepts his arguments – as though she is not already convinced. It is just that in this case she has found herself the weaker party. Hospitality – the rules of hospitality – would at this moment suit her, but philosophically she is convinced and knows all this herself.

Or does she? For why does she eventually leave Minski alive? She drugs him, steals all his wealth and escapes, but she does not poison him fatally. Sbrigani would prefer that she did in order to ensure their safe escape, but she decides that she cannot. What law does she obey? Surely not the law of hospitality. This is not her home after all. No she leaves Minski alive so that he may awake and return to his criminal ways. His criminality delights her. At least this is the argument that she makes. Yet it would seem that she, like Minski, cannot bring herself to kill a kindred spirit. She is pulled by the pathos of a perverse society. She is drawn to adhere to a paradoxical community. The laws of this community is that nothing matters but the individual’s pleasure (and imagination of pleasure). No other person counts. Not parents, not children, not ordinary ethical obligations. Each libertine resembles Minski’s keep – they are surrounded by swathes of wilderness and preserved behind numerous walls. They are alone. They insist they are alone. But at the same time they are always seeking allies and friends. They form societies (the Sodality Society), they talk to one another endlessly, they imagine that they can agree on the truth – on a truth that ultimately separates them.

Perversely then they do actually believe in hospitality – a difficult, endlessly negotiated, lie-strewn, bloody and carnal hospitality. The poor – those who can be placed in seraglio’s, those who are selected as victims – are not provided with any hospitality whatsoever. They are disregarded as people. They are beneath recognition and philosophical discourse. Their suffering serves the utilitarian purpose of enhancing pleasure. Their vibrations of pain exacerbate the discharge of the libertine and the community of libertines. Despite their denial of empathy, common feeling, the libertines do struggle to form a community. They are incapable of withdrawing from society altogether. They cannot, as I say, even withdraw from the prospect of law. Their criminality is simply an imaginary adherence to the dictates of Nature.

And I wonder if parallels can be drawn between the community of libertines and the community of socially engaged art – each just as violent in their determination of who and who does not deserve hospitality? Each also involving seraglios.

The tale of Minski indicates that there is nothing simple about social interaction. Nothing is simply mobilised. There is no necessity that things should end well, that a reasonable, aesthetically ground community should emerge. There are all kinds of possibilities. There are Minski’s exploits. There are Juliette’s travels. There is their shared grudging, uncertain, passionate and dispassionate hospitality.