Lene Schneider-Kainer’s story begins with her parents, who moved in prominent Viennese social circles. Her mother converted to Judaism and her Jewish father Sigmund was an illustrator, able to get her into art school even though women were not officially allowed to attend. In 1909 she moved to Paris to continue her art studies, where she met her husband, the Munich doctor, painter, graphic artist, poster artist and stage decorator Ludwig Kainer. They married in Hungary in October 1910, and their son Peter was born a year later. In 1912 they moved to Charlottenburg in Berlin, where they were part of a circle of artists and intellectuals that included the composer Arnold Schönberg, the novelist and poet Franz Werfel, the artist Herwarth Walden and the poet Else Lasker-Schüler.

Lene Schneider-Kainer’s story begins with her parents, who moved in prominent Viennese social circles. Her mother converted to Judaism and her Jewish father Sigmund was an illustrator, able to get her into art school even though women were not officially allowed to attend. In 1909 she moved to Paris to continue her art studies, where she met her husband, the Munich doctor, painter, graphic artist, poster artist and stage decorator Ludwig Kainer. They married in Hungary in October 1910, and their son Peter was born a year later. In 1912 they moved to Charlottenburg in Berlin, where they were part of a circle of artists and intellectuals that included the composer Arnold Schönberg, the novelist and poet Franz Werfel, the artist Herwarth Walden and the poet Else Lasker-Schüler.

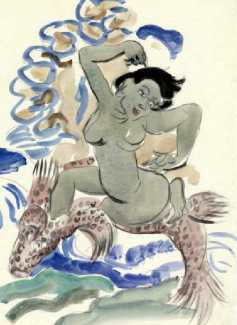

Lene Schneider-Kainer made her debut as an artist in 1917 with an exhibition at the Gurlitt gallery, which included a number of erotic images considered quite shocking at the time. The artistic highpoint of her career was the period between 1919 to 1922, when she became well known as a painter and illustrator, enjoying acclaim in Berlin and selling her works abroad. For a while in 1925 she ran a fashion art salon in Rankestrasse, which she decorated like a stage with her pictures and brightly-coloured fabrics.

Ludwig Kainer had several affairs during this period, and not to be outdone Lene started a relationship with the novelist Bernhard Kellermann. An established novelist and journalist, Kellermann was best known for his 1913 novel Der Tunnel (The Tunnel), which sold more than a million copies and was the basis for four films. Unlike Schneider-Kainer, Kellermann was not Jewish, but his socially critical novels were popular among Jews.

In 1926, Schneider-Kainer and her husband divorced after sixteen years of marriage, and she set out on an epic trip with Kellermann, sponsored by the Jewish-owned newspaper Berliner Tageblatt — he wrote about the trip, and she took photographs and illustrated their encounters. Their itinerary was unusual for the time, following the allure and romance of places in the East little known to European readers. ‘A new life,’ she wrote in her diary.

On their return via the Trans-Siberian Railway, she presented a selection of her works from Asia in Berlin, Magdeburg, Stuttgart, Kiel, London and Rome, and produced illustrations for the magazine Die Dame. During an extended visit to the Balearic islands in 1932 she decided not to return to Germany because of the power takeover by the National Socialists, so settled first in Mallorca and later in Ibiza, where she started an artists’ colony. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, she left for New York.

She had successful exhibitions in Mallorca, Barcelona, Copenhagen, New York and Philadelphia, then in 1954 she decided to settle in Cochabamba in Bolivia, where she assisted her son Peter in establishing a textile factory producing Native American designs for export to the United States.