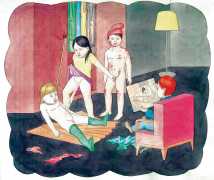

As will be immediately apparent, this portfolio consists of images of young children exploring their sexuality in explicit detail, and raises the longstanding issue of whether the depiction of naked children in art, especially where their sexuality is concerned, is justified.

Note that we deliberately say ‘justified’ rather than ‘acceptable’, as we believe that art (in the widest sense) is an important way of exploring what are often considered taboo subjects. In these paintings the artist uses his skill and imagination to help us understand his, ours, and Bataille’s approach to the wide variety of sexual and sensual pleasure which can be accessed, and acted on appropriately, when we acknowledge our infantile urges.

If you believe that paintings of naked children involved in what are usually considered ‘forbidden’ behaviour are beyond the pale of artistic exploration, then please move on quickly to art that you find more acceptable. You have been warned!

‘It is an instructive fact,’ wrote Sigmund Freud in 1905 in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, ‘that under the influence of seduction children can become polymorphously perverse, and can be led into all possible kinds of sexual irregularities. This shows that an aptitude for them is innately present in their disposition.’ Freud theorised that many young children have unfocused pleasure/libidinal drives, deriving pleasure from any part of the body, including bodily fluids and what comes out of their bodies. He suggested that polymorphous perverse sexuality continues from infancy through to about age five, progressing from the oral stage, through the anal stage, to the genital stage. Only in subsequent developmental stages do children learn to constrain their drives towards socially accepted norms. Freud wrote that undifferentiated impulse for pleasure, including incestuous and bisexual urges, are quite normal. Lacking knowledge that certain modes of gratification are forbidden, the polymorphously perverse child seeks gratification wherever it occurs. For Freud ‘perversion’ was a non-judgmental term; he used it to designate any behaviour outside the socially acceptable norms of his era.

‘It is an instructive fact,’ wrote Sigmund Freud in 1905 in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, ‘that under the influence of seduction children can become polymorphously perverse, and can be led into all possible kinds of sexual irregularities. This shows that an aptitude for them is innately present in their disposition.’ Freud theorised that many young children have unfocused pleasure/libidinal drives, deriving pleasure from any part of the body, including bodily fluids and what comes out of their bodies. He suggested that polymorphous perverse sexuality continues from infancy through to about age five, progressing from the oral stage, through the anal stage, to the genital stage. Only in subsequent developmental stages do children learn to constrain their drives towards socially accepted norms. Freud wrote that undifferentiated impulse for pleasure, including incestuous and bisexual urges, are quite normal. Lacking knowledge that certain modes of gratification are forbidden, the polymorphously perverse child seeks gratification wherever it occurs. For Freud ‘perversion’ was a non-judgmental term; he used it to designate any behaviour outside the socially acceptable norms of his era.

In his 1928 Histoire de l’oeil (Story of the Eye), Georges Bataille takes polymorphously perversity a stage further, exploring how very young, unfocused and unbridled libidinal urges can extend into older children, and of course adulthood. Narrated by an unnamed young man looking back on his exploits, Histoire de l’oeil describes the sexual perversions of a pair of teenage lovers. Simone is his primary female partner, but the narrative includes two important secondary figures, Marcelle, a mentally ill sixteen-year-old girl who comes to a sad end, and Lord Edmund, a voyeuristic English émigré aristocrat. Though often portrayed as pure pornography, interpretation of the story has gradually matured to reveal considerable philosophical and emotional depth, its imagery built upon a series of metaphors which in turn refer to philosophical constructs developed in Bataille’s wider work on the erotic, including the eye, the vagina, the anus, the testicle, the egg, the sun and the earth – uncomfortable connections which Johannes Spehr explores in this privately-commissioned portfolio.

The children’s colour-illustrated book style is deliberate, offering us a double- or triple-take on the seeming innocence of childhood play, which in its unboundaried form leads to the sort of perversities explored by Bataille in Histoire de l’oeil. The big question is, are such ‘natural’ drives worthy of exploration in art and literature, or better left buried?

We are very grateful to Hans-Jürgen Döpp for these images; Hans-Jürgen, the compiler of many books on erotic art, curates the Venusberg online gallery and bookshop which you can find here.