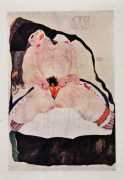

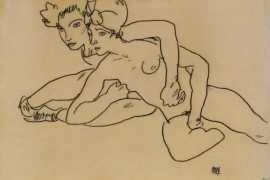

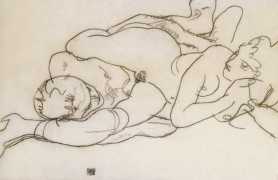

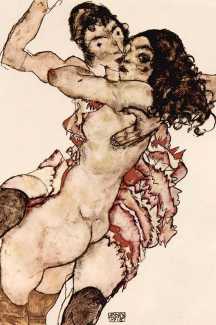

Literally lifting the skirts of bourgeois respectability, Egon Schiele’s unashamed nude drawings deserve far more notoriety than just their elicit subject matter. Schiele’s naked bodies are spectacularly modern, pushing the nude well beyond anything his contemporaries were doing as he lay bare what he felt human sexuality and desire was all about. Schiele’s erotic drawings also make some interesting allusions towards his bohemian personal life. It has been suggested, for example, that the 1915 image of two women locked in a close embrace, ‘Two Girls Embracing (Friends)’, mirrors Schiele’s indecision between his lover Wally and his wife Edith.

Literally lifting the skirts of bourgeois respectability, Egon Schiele’s unashamed nude drawings deserve far more notoriety than just their elicit subject matter. Schiele’s naked bodies are spectacularly modern, pushing the nude well beyond anything his contemporaries were doing as he lay bare what he felt human sexuality and desire was all about. Schiele’s erotic drawings also make some interesting allusions towards his bohemian personal life. It has been suggested, for example, that the 1915 image of two women locked in a close embrace, ‘Two Girls Embracing (Friends)’, mirrors Schiele’s indecision between his lover Wally and his wife Edith.

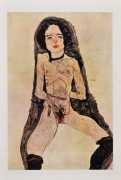

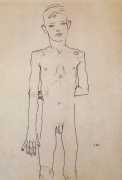

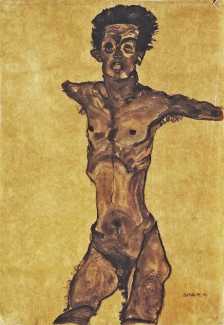

Schiele did not just paint the female nude; he often used himself as a model. He believed that he had to tell the truth about the human condition through his art, ad so would always be condemned to be misunderstood by wider society. In the 1910 drawing ‘Nude Self-Portrait in Gray with Open Mouth’ he contorts his own body into a crucifix, alluding to his identification with a Christ-like sacrifice.

Schiele did not just paint the female nude; he often used himself as a model. He believed that he had to tell the truth about the human condition through his art, ad so would always be condemned to be misunderstood by wider society. In the 1910 drawing ‘Nude Self-Portrait in Gray with Open Mouth’ he contorts his own body into a crucifix, alluding to his identification with a Christ-like sacrifice.

For a brief background to Egon Schiele’s drawings and their context, here is the catalogue introduction by Bernd Apke to the 2005 Leopold exhibition entitled The Naked Truth.

When, in 1909, Egon Schiele founded the Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group) with a number of fellow students from the Viennese Art Academy, and then resolved with these to leave that training institution, he had taken what was to prove a decisive step for one who was then only nineteen years old. Schiele sought to distance himself from the traditional curriculum of the Academy, and from those who had taught him there, artists who had decorated the Historicist buildings that were added to the Viennese Ringstrasse from the 1870s to the 1890s. As early as 1907 Schiele had turned, instead, and with increasing enthusiasm, to the work of Gustav Klimt, although swiftly abandoning the ornamental Jugendstil aspect of Klimt’s style. Nonetheless, even after 1910 – the first year in which an ‘expressionistic’ manner began to dominate in his work – Schiele was still much indebted to Klimt. The importance for Klimt of line and outline effectively found its continuation in the work of the younger artist.

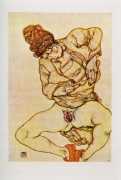

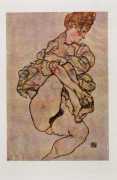

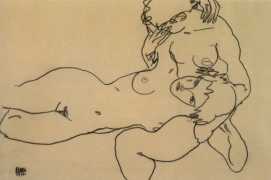

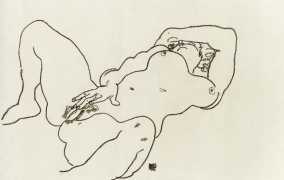

Each artist used line, however, in a distinct fashion. While Klimt surrounded his figures with an evenly flowing outline, Schiele’s lines are brittle, occasionally broken and suggestive of fragility. In Schiele’s drawings no indications as to spatial context or objective components distract the viewer’s attention from the figure. In placing this on an empty drawing surface, he is able to insist on its far from merely representational character. Schiele aims not at objective perception, but at subjective and one-sided participation; it is this, too, that characterises his figures, crucial to which is their partial or total nakedness. Schiele did not require his models to adopt classical poses or to simulate classical movement; he posed them in a fashion that was for a long time interpreted as ‘ugly’. He focused on fragments of the body, altogether omitting those parts that did not interest him – sometimes the head or the limbs. Very occasionally, this would be due to ‘the sheet having become too small in one particular area during the course of the work’ (for Schiele attended to ‘composition’ only after throwing himself into the act of drawing), but the fragmentation of Schiele’s figures is, above all, an expression of the very personal gaze that he fixed on his model; whatever did not interest him was simply ignored. This ‘self-centred’ approach also finds a reflection in Schiele’s use of colour, which is almost never used descriptively, but reveals an obsession with particular, energetically ‘charged’ features. This is the epitome of Schiele’s overall approach to drawing: Schiele only ever drew after nature. His colours, on the other hand, were always applied from memory and without reference to the model. Memory, in the case of Schiele, served both to mask reality and to bring forth a world of its own.

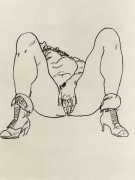

Schiele’s work is particularly notable for the fact that he willingly eschewed the role, cultivated by Klimt, of the disinterested pleasure-seeker. In the language of developmental psychology: in as far as Klimt may be compared to an adult, secure and unwavering in his own role, Schiele is the pubescent, still fascinated by experiment. Schiele appears naked in his own drawings just as often as do his models. He was particularly fascinated by sexuality, and in this area he broke numerous contemporary taboos. In 1910, thanks to his friendship with the gynaecologist Erwin von Graff, he gained access to a women’s clinic and there made a series of drawings of naked pregnant women. He shows women flaunting their genitalia and women masturbating. He records lesbian as well as heterosexual coupling. And, in serving as his own model, he is himself simultaneously an exhibitionist and a voyeur, and always in confessional mode. His models, moreover, are invariably self-conscious and they often exchange glances with the artist – and, by extension, with the viewer.

Sometimes the titles of Schiele's works – often supplied, quite spontaneously, by the artist – allude to the breaking of a taboo, as in the case of the naked self-portrait, which he imbues with an ostensibly religious sense of mission, by titling it Preacher. But Schiele did, of course, have a mission: to demonstrate that the individual human being is imbued with sexuality and that this was arousing, yet not so neat and orderly as Klimt would have us believe. One might characterise Klimt as a pleasure-loving pagan, while Schiele often appears to be not at all happy about the pressure that sexuality is able to exert on him.