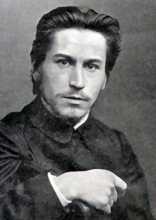

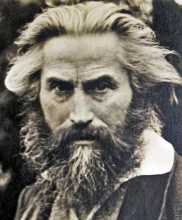

Born the son of a confectioner in Lübeck in northern Germany, Hugo Reinhold Karl Johann Höppener demonstrated artistic talent at an early age. Around 1886 he met the artist and ‘apostle of nature’ Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (1851–1913), and joined Diefenbach’s free-thinking rural commune at Höllriegelskreuth near Munich. On Diefenbach’s behalf Höppener served a brief prison sentence for public nudity, earning him the name Fidus – ‘the faithful one’ – from Diefenbach. From that point Höppener used the pseudonym Fidus for all his work.

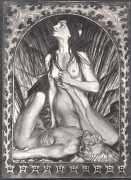

In 1892 Höppener moved to Berlin, set up another commune, and worked as an illustrator on the magazine Sphinx. His work appeared frequently in Jugend and other illustrated magazines. He created many stylised drawings, especially for book decoration, as well as ex-libris, posters and prints. He was one of the first artists to use advertising postcards to promote his work. Though bisexual rather than gay, Höppener also contributed to the early homosexual magazine Der Eigene, published by Adolf Brand.

In 1893 he met the teacher and writer Amalie Altmann-Reich, with whom he lived in what they called ‘an ideal-free partnership’; they had a daughter, Hilde, in 1896. In 1899 Höppener met and married Elsa Knoll, and they also had a daughter, Trude, followed by a son, Holger. Höppener married again in 1922, this time to Elsbet Lehmann-Hohenberge, who brought her daughter Helga Wagner into the growing family.

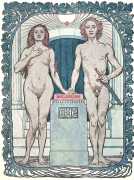

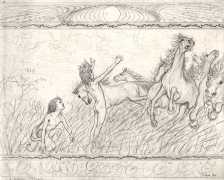

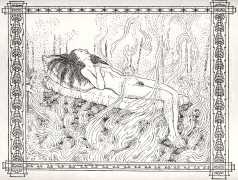

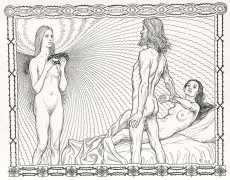

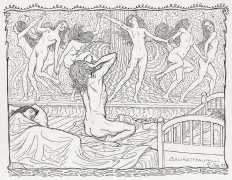

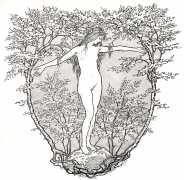

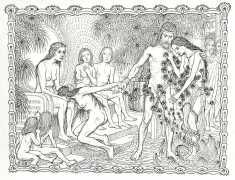

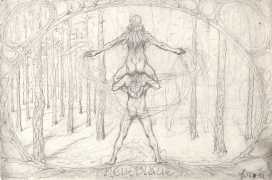

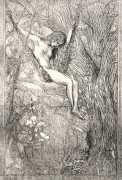

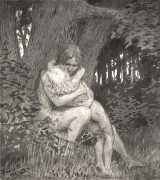

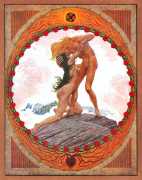

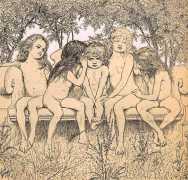

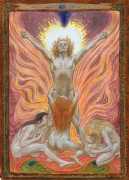

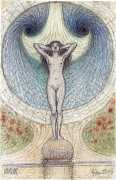

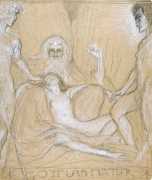

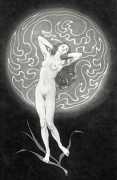

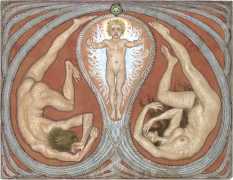

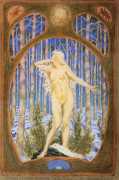

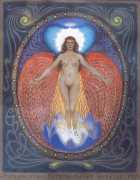

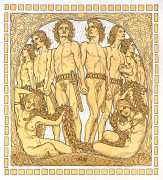

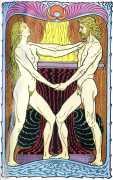

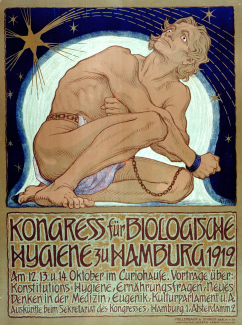

Hugo Höppener held mystical Theosophical beliefs, and became fascinated by German mythology. His early illustrations contained dream-like abstractions, while his later work was characterised by motifs such as peasants, warriors, and other naked human figures in natural settings. He often combined mysticism, eroticism, and symbolism, in Art Nouveau and Secessionist styles. By 1900 he was one of the best known painters in Germany, and had come under the influence of writers such as Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Heinrich and Julius Hart, and the anti-materialist garden city and Wandervogel movements. In 1912 he designed a famous poster for a congress on ‘biological hygiene’ in Hamburg, showing a man in the process of breaking his bonds and rising up to the stars.

After 1918 interest in Fidus’s work as an illustrator ebbed. Despite his enthusiasm for the ideology of the Nazi Party, of which he became a member in 1932, he did not receive the support of the Nazi regime. In 1937 his work was seized and the sale of his images was forbidden. By the time he died in 1948 in Woltersdorf, his art had been almost forgotten. It was rediscovered in the 1960s, and directly influenced the psychedelic art which began to be produced at that time.

We would like to thank our Russian friend Yuri for suggesting the inclusion of this artist.