We have given this comprehensive collection of Trevor Brown’s work the title of his first published collection of Baby Art material, to underline how difficult it is for the art world to acknowledge the quality and value of much transgressive art.

In 2008 the magazine Japan Today printed an excellent article about Brown and his work, written by C.B. Liddell, which offers an honest and balanced overview of the man and his work, including important insights from the artist himself.

Is there more to the controversial art of Trevor Brown than meets the eye?

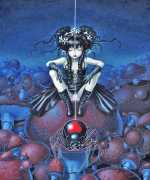

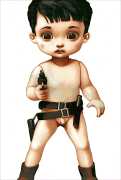

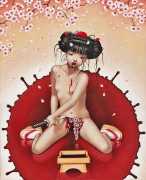

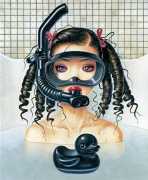

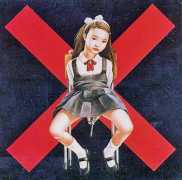

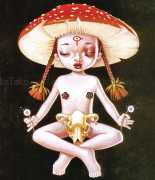

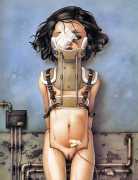

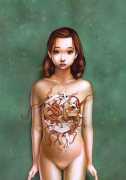

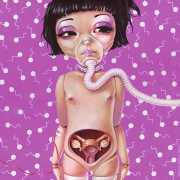

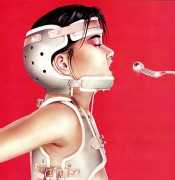

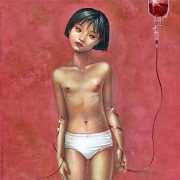

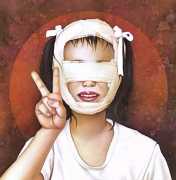

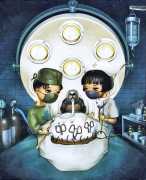

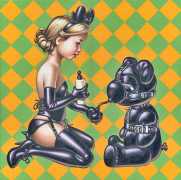

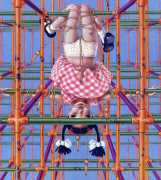

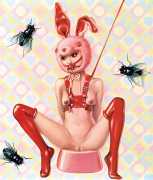

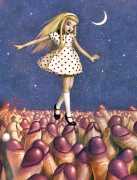

Exiled English painter Trevor Brown is one of the most controversial, misunderstood, yet talented artists in Japan. His paintings of funny, cute, but sinister doll-like creatures, lolitas and teddy bears inhabiting a bizarre world of medical, masochistic and macabre imagery seem to emanate from a perpetual twilight zone, where innocence is inextricably enmeshed with – but never fully corrupted by – evil.

Yet even though this fascinating cocktail is an addictive passion for Brown’s fans, who religiously buy his paintings and books, it is definitely not everybody’s cup of tea. Over the years, the artist has received death threats and been accused of everything from paedophilia to Nazism, via Satanism and sadism. Reflecting the hysteria that Brown sometimes attracts, one reviewer said, ‘The toilet bowl inside this artist’s brain is overflowing with blood culled from a massive fetish orgy starring a horde of underage Japanese goth sluts for whom the more freakish, unimaginable terrain of human behaviour is the norm.’

Brown himself has become used to attacks like this. ‘Discussion of my work always falls into opposing factions, those who love it and those who hate it,’ he says. Completing the critics’ negative image of Brown is the fact that, since 1994, he has lived and worked in Japan, a country known for its easy-going attitude or indifference to certain unusual types of sexuality, be it tentacle porn, paedophilic manga, and shibari rope bondage. The implication in all this is that somebody like Brown is here because he wouldn’t be tolerated in his native England. But, of course, this is nonsense, as proved by Turner Prize-nominated British artists Jake and Dinos Chapman, whose work routinely features naked children and Nazi iconography. If Brown is an exile in Japan, it is by choice. ‘I simply fell in love with all things Japanese, and with a Japanese girlfriend holding my hand I left my home country. It was a leap into the unknown.’

Now married to that same woman, Brown is comfortable here and generally approves of the live-and-let-live attitude he has encountered. ‘The Japanese mind-your-own-business disposition is so great they’ll walk past someone lying on the ground bleeding to death,’ he says. ‘But generally it’s mostly admirable.’ The attraction is mutual. Although most of his paintings are still sold to Western buyers, Brown has gained popularity in Japan far beyond the dreams of most Western artists working in the country. This is expressed in book sales, illustrations for magazines and CD covers for local musicians. What’s the secret of his success?

‘I don’t really know many other gaijin artists,’ he answers. ‘But I suspect there could be an unseen number of aspiring artists struggling to be big in Japan. Japan still retains a sort of prestigious trendiness. I’ve never tried hard at attempting to appeal to the Japanese, which might be a mistake many artists make, but have just tried to stay my Western self, and let the influence of being in Japan naturally seep into my work.’

While the Japanese seem comfortable with having Brown in their midst, elsewhere it’s a different story. Opposition to his art remains strong. He agrees that this is partly because it is so easy to understand his work in the wrong way rather than to just be fashionably mystified by it, as happens with other contemporary art. For the viewer mature enough to advance beyond the hysteria and moral outrage, however, there are several interesting strands to be discerned in Brown’s work. These include the enhanced aesthetic effects of juxtaposing opposites, explorations of female passive-aggressive power, elements of surrealism, traditional British vulgar humour, and an interest in human fragility as filtered through J.G. Ballard’s novel Crash.

But Brown believes that cultivating ambiguity for its own sake is also important. ‘You want to make people think about how things affect them,’ he explains. ‘To that end I consciously make my work ambiguous and open to misinterpretation, deliberately sending out conflicting messages.’ The ambiguity extends to the figures in his paintings – the ages of the girls are unspecified, or they may simply be dolls. This means that any paedophilic reading ultimately depends on the viewer choosing to see things this way, an act revealing more about them than the artist.

Putting art and its multifaceted interpretation to one side, what are Brown’s own attitudes to sex? Is he the sort of person you’d be insane to let near your children? ‘I’m actually way more conservatively normal, boring and conventional than your imagined art ogre,’ he responds. ‘I’m not particularly sexually attracted to children at all. Things change, however, in the teens, and I’ve had fourteen-year-old female fans that have written to me who haven’t sounded exactly stupid. It’s utterly ridiculous setting the age of sexual activity at eighteen and anything below that is ‘child abuse’ territory. Many teenagers are clearly no longer kids at that age, so they shouldn’t be treated as such. I don’t have any solutions, but we do need a little common sense to prevail.’

Asked his views on a wide range of sexual behaviour, Brown makes it clear that he stands for the principle of consent and the autonomy of the individual. His belief that the individual should decide what he or she likes artistically, does sexually, or simply thinks, rather than having it prescribed by interfering busybodies, swims against the tide of the times. In the west, increasing social diversity is leading to less and less tolerance for anything that might be regarded as offensive by any one particular group. Those in authority are also increasingly prone to respond to groundless rumours and anonymous accusations, as Brown has found out to his detriment. ‘I’ve been banned by Paypal for life because someone complained to them about my work,’ he says. ‘They immediately and without warning closed my account and pocketed my sizable funds for six months. They deemed my work to be pornography involving minors. When I tried to dispute this libellous accusation, they told me the matter was considered closed, and any further correspondence about this issue would go unanswered. Judge, jury and executioner!’

In the face of such opposition, it’s very much to Brown’s credit that he has stuck to his guns, painting what he feels inspired to, rather than bowing to convention. ‘I’m no art martyr,’ he says with a note of stoic self-deprecation. ‘I’m not even sure if I’m an outcast by choice. I do what I do. And I have a belief in myself and the strength of conviction to follow my own artistic ideas against popular opinion. So while the weather is fine, I’ll continue to skate on thin ice, whether for your delight or your derision.’

This is a slightly abridged version of the article, which can be found here.