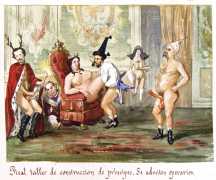

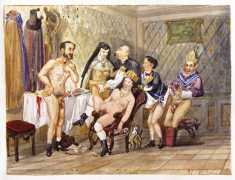

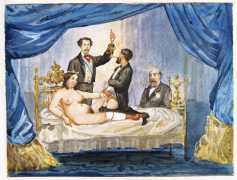

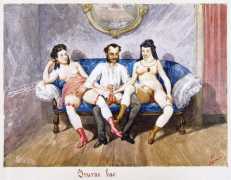

In 1991 Ediciones El Museo Universal published an album of 89 watercolours, originally titled Los Borbones en Pelota (The Bourbons at the Ball). The watercolours, signed ‘Sem’ or ‘Semen’, are thought by most art historians to have been painted by Valeriano Domínguez and Gustavo Adolfo Becquer sometime during 1868–9, though some researchers believe they are actually the work of Francisco Ortego Vereda, a radical opponent of the Royalists.

In 1991 Ediciones El Museo Universal published an album of 89 watercolours, originally titled Los Borbones en Pelota (The Bourbons at the Ball). The watercolours, signed ‘Sem’ or ‘Semen’, are thought by most art historians to have been painted by Valeriano Domínguez and Gustavo Adolfo Becquer sometime during 1868–9, though some researchers believe they are actually the work of Francisco Ortego Vereda, a radical opponent of the Royalists.

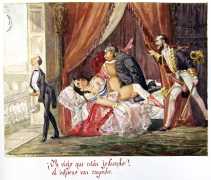

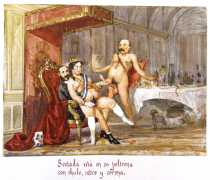

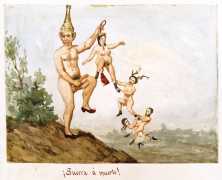

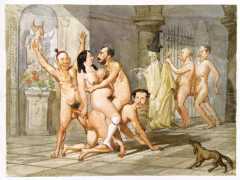

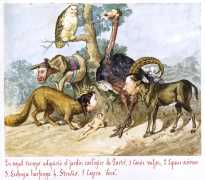

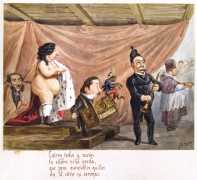

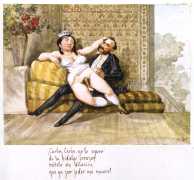

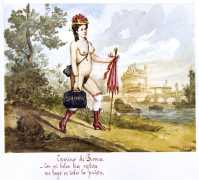

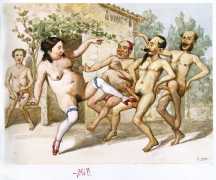

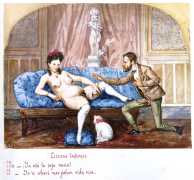

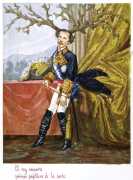

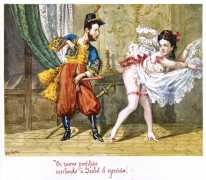

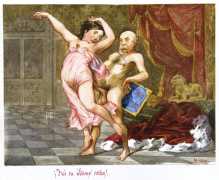

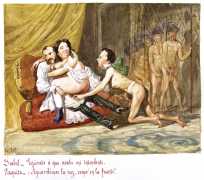

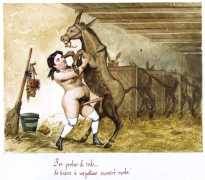

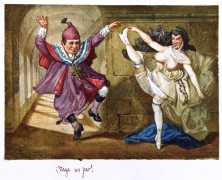

The album of satirical plates, politically barbed and explicitly sexual, was made between the moments immediately before the Revolution of 1868 and the beginning of the reign of Amadeo I. There are in fact 107 plates altogether, of which around half are erotic, featuring the Spanish Court of Queen Isabella II, her husband Francisco de Paula (represented as a cuckold in all the drawings where he appears), the queen’s confessor Antonio Maria Claret, and an array of ministers, priests and nuns, all in permanent orgy and with devastating political satire. Many of the images are accompanied by sharp allusive texts.

The album was missing until 1986, when it was acquired by the National Library of Spain, and in 2012 the Institución Fernando Católico in Zaragoza published a complete, detailed and fully-illustrated album with excellent reproductions of all the paintings.

The art historian Lou Charnon-Deutsch, in an essay titled ‘The Pornographic Subject of Los Borbones en Pelota’, explains some of the context of the album:

The two dimensions of the Becquer watercolours, the sexual and the political, intersect in important ways that have been touched on only briefly by commentators. In the introduction to the 1991 Sem collection, an unnamed editor speculates that with this publication the famed poet Gustavo Adolfo Becquer will be rescued from four generations of purgatory, and located not in the paradise expected for the author of the sublime Rimas y leyendas (Rhymes and Legends), but in hell.

It is not that Gustavo and his brother Valeriano will go to hell for what they have created, but that their lives will at last be seen as a living hell, a chaos of sentiment and sex that has remained partially veiled to us until some unnamed party sold the Sem watercolors to the Biblioteca Nacional. Now we can paint a more accurate and nuanced picture of the extent to which Queen Isabella II, featured in so many of the watercolours, is still used to reveal both the seamier side of her sexual deportment and the vision of the artists who imagined her sexual excess. For modern-day viewers the queen’s body not only bears evidence of the terrible nothing behind the lifted veil, it provides a mirror that permits us to view Isabelline society for what it really was, how at odds the fleshy and grotesque body of the queen seems with the ethereal spectre of Becquerian rhymes and legends.

Ironically, our modern use of the queen’s body as a mirror of the artist’s and poet’s disordered lives and times tallies well with the narcissistic love object that peoples Becquer’s works, the woman who the narrator of the poem ‘El rayo de luna’ writes, ‘thinks like I think, likes what I like, hates what I hate, a kindred spirit, the complement to my being’. If Becquer imagined the essence of poetry as a veiled, ethereal woman, we imagine the essence of Becquer as a soul tortured by the vulgarity and excesses of Isabella’s reign, personified in the queen’s wanton sexual activities.

Poverty, venereal disease, dissipation, broken marriages, burdensome family responsibilities, and changing political and professional alliances all contributed to the untidy existence of the Becquer brothers, but they do not explain why they may have chosen the queen and her entourage as their target for the caricatures they produced and possibly circulated among their friends, especially since they were under the protection of the court before it disbanded. Nor do they explain the emphatically obscene content of so many of the sketches.

To understand the anecdotal and figural content of the Sem watercolours it is necessary to explore a wide range of conventions and discourses that extend beyond the artists’ personal trajectories – the influence of traditional French caricature; classical iconography; nineteenth-century Spanish anticlericalism and political cynicism; the conventional use of women’s bodies to express what is on a man’s mind; the importance of speaking for the queen; and the vagaries of Isabella’s personal life and how that life was characterised by the novelists and artists of the day.

For more information, and to see the complete series of the Sem watercolours, the authoritative source is the edition published by Institución Fernando Católico in Zaragoza, with an introduction by Isabel Burdiel, now in its third (2020) edition.