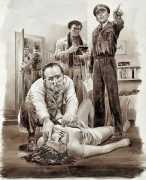

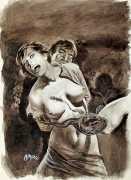

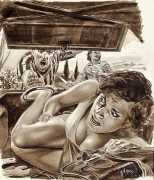

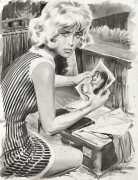

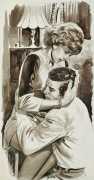

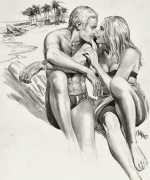

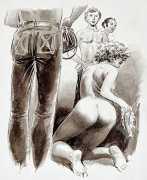

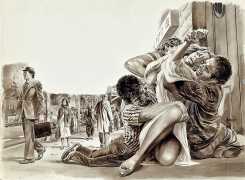

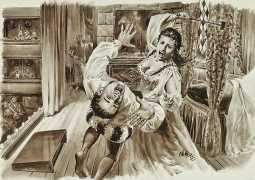

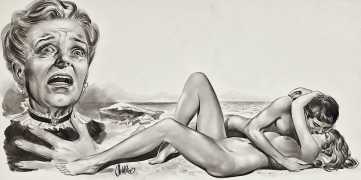

Angelo di Marco is best known for taking bizarre and extreme human-interest stories and creating images of them as horrific masterpieces of draftsmanship. For nearly five decades his drawings appeared in pretty much every French newspaper, as well as on billboards and in countless magazines, illustrating accidents, murders, muggings and shootings, often with a sexual element.

Angelo di Marco is best known for taking bizarre and extreme human-interest stories and creating images of them as horrific masterpieces of draftsmanship. For nearly five decades his drawings appeared in pretty much every French newspaper, as well as on billboards and in countless magazines, illustrating accidents, murders, muggings and shootings, often with a sexual element.

Here we have chosen a selection from many thousands of di Marco/Arcor artworks, mostly those with an erotic content from his work for France Dimanche during the 1980s and 90s.

In November 2008 Mathieu Berenholc from Vice magazine interviewed Angelo di Marco; here are some of his answers.

Do you focus more on the victims?

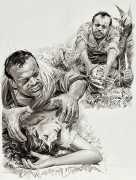

It depends. If I think the victim is the interesting person, I place myself in an angle that faces him or her. For example, if the person is attacked from behind and strangled, then I draw the face of the victim. And if we don’t know the killer’s face yet, then I draw it at an angle so we can see his hands on the victim’s neck. I recently drew something like that. It was a woman who won the lottery. She had been divorced just before winning a fortune, and then she’d been killed, strangled from behind. I drew a bit of the guy’s face, one of his eyes and his forehead. The cops had actually suspected the ex-husband for a while, but they didn’t have any proof so they let him go.

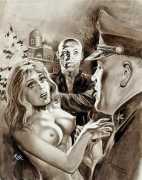

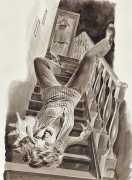

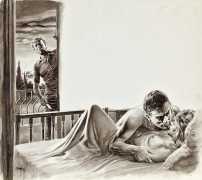

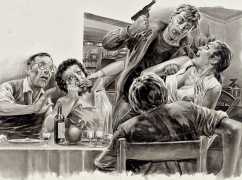

You draw a lot of horrible scenes, but they never have blood in them. There’s fear, but no gore.

I always try to illustrate the suspense, the instant of shooting, robbing or stabbing. The intensity of the victim’s feelings, posture and expression is much stronger than the pain itself. In my drawings the victim knows exactly what’s happening to them, and that’s what’s so horrible. And it’s also much more interesting when I’m drawing the attacker, to show the way they have been taken over by their rage.

Do your drawings help you understand humanity?

That might be pushing it a bit, but I do have my views. There’s a barbarian side of us that you can see throughout history. Animals don’t have a conscience. They often do horrible things without knowing it.

Have any of the stories that you’ve illustrated haunted you?

No, I try to free myself from it. Once I finish my drawing, even if it has a dark side to it, I deliver it and that’s that. I stop thinking about it. But some people must get scarred by the things they see. It can mark their lives, or saddens them, or gives them a gloomy or a withdrawn side. But not me. I don’t think about it. I tell myself that I have to forget it or I’d go crazy.

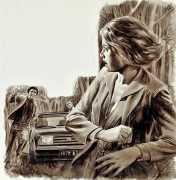

Maybe that’s why there’s such a distance in your drawings?

Maybe, or maybe the distance comes from the fact that I start from scratch every time I begin a new drawing. I think of what happened, I put myself in the characters’ shoes, and then I put them into place in the way I imagine the situation. I show the drama through the faces, the gestures, the behaviour, often exaggerating perspective or viewpoint for added drama.