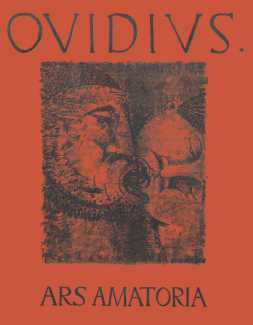

The Roman poet Ovid’s Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love) is a classic of instruction about intimate relating, and even though written two thousand years ago (it is thought in 2CE) many of Ovid’s ideas about love (which for him pretty much equates with sex) remain more or less pertinent today.

The Roman poet Ovid’s Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love) is a classic of instruction about intimate relating, and even though written two thousand years ago (it is thought in 2CE) many of Ovid’s ideas about love (which for him pretty much equates with sex) remain more or less pertinent today.

These rather frivolous poems had a momentous influence on later European civilisation – every educated person with the slightest interest in the subject read them. Unfortunately much of his humour was lost on medieval interpreters, and they often discussed his ideas over-seriously in the context which came to be known as courtly love, a concept which would have been alien and ridiculous to Ovid. His beloved was typically a pretty but ordinary courtesan, not a noble lady in a tower. He makes it clear repeatedly that for him love is a game much like poker, demanding great powers of strategy and deception.

If his voice seems amazingly contemporary, it is largely because of his frank pleasure in sex for its own sake.

Here is an extract from Book 1, Advice to Young Women:

Avoid those men who profess to looks and culture,

who keep their hair carefully in place.

What they tell you they’ve told a thousand girls:

their love wanders and lingers in no one place.

Woman, what can you do with a man more delicate than you,

and one perhaps who has more lovers too?

You’ll scarcely credit it, but credit this: Troy would remain,

if Cassandra’s warnings had been heeded.

Some will attack you with a lying pretence of love,

and through that opening seek a shameful gain.

But don’t be tricked by hair gleaming with liquid nard,

or short tongues pressed into their creases:

don’t be ensnared by a toga of finest threads,

or that there’s a ring on every finger.

Perhaps the best dressed among them all’s a thief,

and burns with love of your finery.

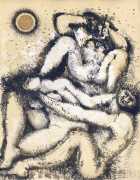

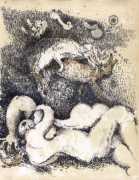

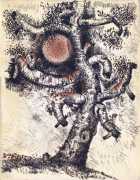

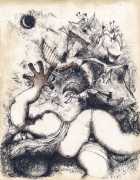

This portfolio of 25 large prints, many in two and three colours, was made at the height of Righi’s career, and in his inimitable accomplished and witty style complement Ovid's text (in an excellent English translation by Rolfe Humphries) perfectly.

The titles of the plates are:

Frontispiece

BOOK ONE

The arm

‘So, they are all carried off, these girls’

‘Why, in your foolishness, constantly tend to your hair?’

‘Roamed a snow-white bull, glory and pride of the herd’

‘Finally had her way, devising a heifer of maple’

‘But why should you be wrong? Untried delights are a pleasure’

‘Hail Bacchus! Hail Hymenaeus! So are the god and his bride

joined on the marriage-bed’

‘She was the one whom rape taught he was really a man’

BOOK TWO

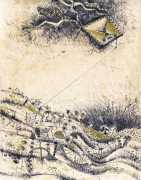

The leg

‘Set no snares for the dove, haunting the eaves of the tower’

‘Help her slip off her mules, help her, again, put them on’

‘Praise her dance and her song’

‘Wild with desire, and no stream ever would stand in their way’

‘There, in the toils of the nets, naked and taken they lie’

‘Bending with left hand low, seen in the statue’s pose’

‘Only the full-grown tree resists the heat of the sunlight’

BOOK THREE

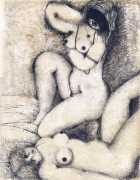

The bosom

‘It would be most unfair for the naked to fight in armour’

‘Theseus abandoned a girl to the lonely shores of the sea birds’

‘Colours as many as flowers born from new earth in the springtime’

‘I am not running my school for Semele’s sake, nor for Leda’s’

‘Orpheus with his lute charmed rocks and trees and wild creatures’

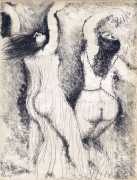

‘Who would doubt that a girl should also be clever at dancing’

‘When she revived, straightway she tore the gown from her bosom’

Recapitulation

The Righi-illustrated Ars Amatoria was published by Ferdinand Roten Galleries in Baltimore, in a limited, numbered and boxed edition of 155 copies.