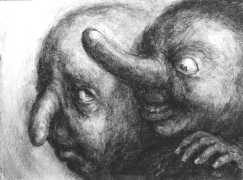

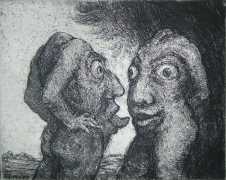

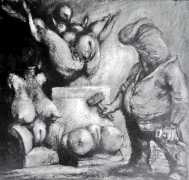

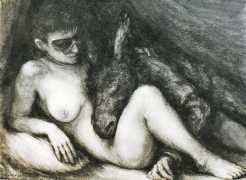

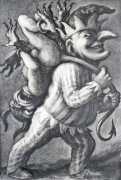

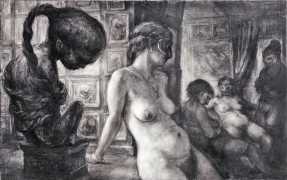

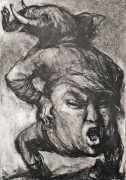

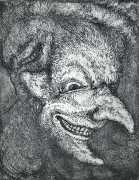

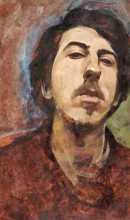

Paul Rumsey is a British graphic artist who works in the tradition of the grotesque and the fantastic. He grew up in Chelmsford in eastern England, and studied art at Colchester School of Art before embarking on a three-year Batchelor of Art course at Chelsea College of Arts in London.

Paul Rumsey is a British graphic artist who works in the tradition of the grotesque and the fantastic. He grew up in Chelmsford in eastern England, and studied art at Colchester School of Art before embarking on a three-year Batchelor of Art course at Chelsea College of Arts in London.

Rumsey has written such a good autobiographical article, which you can find here, that we can do no better than let him speak for himself about his development as an artist. We reproduce here around a third of that article.

Things went wrong from the first hour of my first day at school. We were told to write our ABC. I wrote a couple of capital As, got bored and prompted by the shape turned the rest into a row of boats. I was drawing happily until I found the teacher standing over me. She said that babies couldn’t be trusted with nice school books, so I would spend the rest of the week writing with chalk on a piece of slate. Sitting in the corner, scratching away with the crumbling chalk, smirked at by my classmates, epitomised my school days. I developed a deep hatred for the teacher and for school in general. My attitude was resistance and defiance.

When I was ten I went into class and found the boys huddled around a colour reproduction of Rubens’ Three Graces. The teacher admonished us that this was art, not smut, and that the human body was a beautiful thing. I begged my parents for a book on Rubens and they bought me Recollections of Rubens by Burckhardt, my first art book, which I still have.

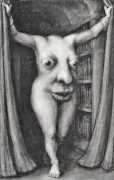

At sixteen I started the foundation course at Colchester School of Art and grew my hair long. I discovered some books which became important formative influences – the Dover books on graphic art including Alfred Kubin’s Dance of Death drawings, Goya’s Caprichos, Disasters of War and Disparates and Piranesi’s Prisons, and novels, including the Mervyn Peake Titus trilogy, Kafka, and Elias Canetti’s Auto-da-Fé, whose protagonist is a mad librarian who has to unpack the shelves in his head before he sleeps.

My tutors at Colchester disapproved of the influences I drew upon. They taught that art should only be done from observation, cool and objective. When it was time to do a body of work to apply for a BA course, I was told I would never get anywhere doing the weird stuff, so I started to work in a more realist manner, influenced by Lucian Freud and Spencer. At the end of the foundation course I won the Munnings Travel Award to Rome and £200. I spent weeks in Florence and Venice, and ended up in Austria at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, which has most of the best Bruegel paintings, and visited the Albertina to look at the Alfred Kubin and Ernst Fuchs drawings.

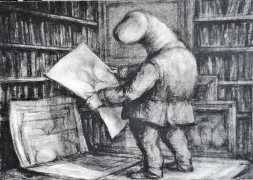

I arrived home and started the three year BA course at Chelsea. I began to feel increasingly isolated. Under the banner of modernism, anything traditional was despised. My drawing ability was seen as a redundant academic skill. I spent a lot of time in Chelsea College library looking up artists which I’d seen when travelling in Europe. I much preferred pre-twentieth century art. Traditional art had no limitations. There was the entire fabric of the world to play with, the diverse shapes of every living thing, solidity, atmosphere, light effects, expression and emotion, fear and desire, allusions to myths and narratives.

I wanted a fresh start. After Chelsea I began thinking about how I used to enjoy art before I went to college, before all the rules that art should be this and should not be that. The first prohibition had been against working from the imagination. I had not drawn from my own head for three or more years. To start myself off I picked up a copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and read through, stopping to draw whenever a picture came into my head, filling sketchbooks with ideas. Such had been the pressure against this kind of work that to begin with I felt guilty to be doing these drawings.

It was 1977. I met my partner, the artist Terry Curling. We discovered that in our teens we had both spent ages looking at the Burne-Jones and Rossetti pictures at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and that we had owned a lot of the same books on the symbolists and decadents. Terry had a wider knowledge of art history and a larger book collection than I did, so she introduced me to a lot of art I hadn’t heard of before. We started to buy a lot of books, cycling around London from Richmond to Hampstead from one second-hand shop to the next, rummaging through stacks of old art magazines, L’Oeil, Burlington, Apollo, drawing catalogues from Christie’s and Sotheby’s piled on the floor as if emptied from a wheelbarrow. We spent so much time doing this that I would have recurring dreams of searching in bookshops, labyrinthine dark basements.

In 1989 our twin girls were born and we moved out of London to Wivenhoe. I started to enter drawings for competitions, won some prizes and began to sell my work. I was included in mixed exhibitions at the East West gallery in London and had my first solo show there in 1996, then solo shows at Gainsborough’s House and Chappel in 1997.

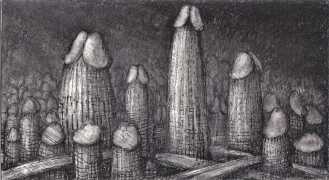

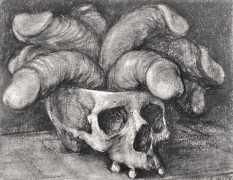

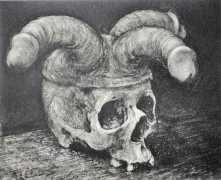

At this time I was asked to do some talks about my work to students, and this made me think more coherently about the traditions and influences from which I was drawing. I came to see the history of art, not as separate layers of sediment or strata but as a living thing like a tree, growing with intertwining stems, alive from root to twig. The tradition of the grotesque is particularly alive in prints. The fantastic is especially suited to the graphic medium, and it is possible to track almost its entire history in etchings, engravings and woodcuts. A fine book, The Waking Dream: Fantasy and the Surreal in Graphic Art 1450–1900, charts this progress through Holbein’s Dance of Death, the macabre prints of Urs Graf, the engravings of Callot, seventeenth-century alchemical prints, scientific, medical and anatomical illustration, emblems, the topsy-turvy world popular prints, Rowlandson, Gillray, Goya, Fuseli and Blake, and into the nineteenth century with Grandville, Daumier, Meryon, Doré, Victor Hugo’s drawings and Redon. In the twentieth century this type of imagery has permeated culture and is found everywhere, in diverse art forms including: the satiric installations of Keinholz, the drawings of A. Paul Weber, the cartoons of Robert Crumb, the animated films of Jan Svankmajer, photographs by Witkin, plays by Beckett, science fiction by Ballard, fantastic literature like Meyrink’s The Golem, Jean Ray’s Malpertuis, the art and writings of Bruno Schulz and Leonora Carrington, films by Lynch, Cronenberg and Gilliam – all are part of a spreading network of connections, the branching tentacles of the grotesque.

This is the tradition to which my work belongs, and when I am drawing I am aware of making connections with every strand of this tradition. The use of fantastic metaphor and poetic allusion allows me great freedom, to portray any idea from the exterior political to the interior psychological. And the materials I work with give me freedom; charcoal is very flexible, and can be wiped, erased, sandpapered and redrawn. It is open to chance effects that can lead to unanticipated directions and solutions. I make constant revisions and alterations. Even with a medium like pen and ink which would favour the permanent, spontaneous, linear mark, I have even found a way, by using sandpaper on card, of reworking whole sections, to end up with the textures, tones and atmospherics I am looking for.

Until recently Paul Rumsey had a website, but it now appears to be unavailable. However, one of his daughters curates his Facebook account here, where you will find regular updates about exhibitions and other news.

We are very grateful to our Russian friend Yuri for introducing us to the work of this artist, and for supplying many of the images.