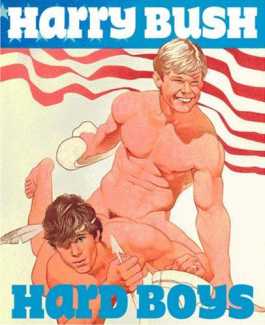

In 2007, thirteen years after his death, almost all of Harry Bush’s published work, as well as many original sketches, were collected thanks to the efforts of a group of friends and fans in a volume published by Green Candy Press entitled Hard Boys. Hard Boys is a 200-page scrapbook showing how many of today’s artists have been inspired by his art. The collection was edited by Robert Mainardi, who also wrote the introduction, while the foreword was written by Thomas Waugh and the afterword by Jim French.

In 2007, thirteen years after his death, almost all of Harry Bush’s published work, as well as many original sketches, were collected thanks to the efforts of a group of friends and fans in a volume published by Green Candy Press entitled Hard Boys. Hard Boys is a 200-page scrapbook showing how many of today’s artists have been inspired by his art. The collection was edited by Robert Mainardi, who also wrote the introduction, while the foreword was written by Thomas Waugh and the afterword by Jim French.

Here are some of the important extracts from Thomas Waugh’s introduction:

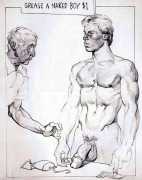

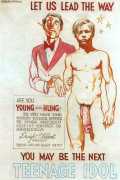

These drawings are historical documents of the decades both before and after the Stonewall watershed – vivid reflections of the emergence of gay erotic culture from the shadowy underground of the 1960s physique alibi, into the bulimic world of aboveground gay erotica consumerism in the 1970s.

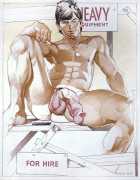

After Stonewall, private mail-order fantasies gradually succumbed to public porn cinemas and a rack of glossy skin magazines on every corner newsstand. The self-conscious jokiness and boldness of the Physique Pictorial narrative ideas of the 1960s had yielded to the in-your-face bluntness of fleshly frenzy. By this time Bush’s coy fun with the borders of the permissible in a physique magazine on the cusp of full-frontal revolution had yielded to the deadly serious supercocks of the new era.

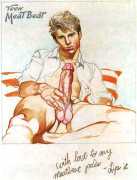

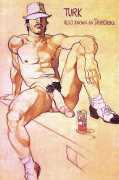

California surfer bimbos have never been my thing, but there is something tremendously moving about Harry Bush’s sustained obsession with these seductively needy and deceptively innocent hulks. Was it in the armed forces that Bush got imprinted with this procession of ambiguously passive-aggressive confrontations with pruriently complicit authority figures?

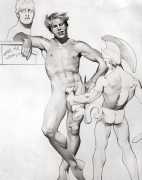

No one can deny the brilliance of Bush’s mastery of both line and shading, his knack for so evocatively capturing anatomy, movement and light, a talent all the more amazing when encountered in the work of a self-taught hobbyist who came into his own upon retirement. No wonder he was notoriously fussy about the faithful reproduction of his drawings.

The comparisons understandably fly fast and furious, whether to J. C. Leyendecker’s stylish art deco elegance, Norman Rockwell’s folksy anecdotal innocence, Blade’s inventiveness with text and caption, Steve Masters’s precision and structure, or Tom of Finland’s marriage of tableauesque choreography and cartoonish excess. Is it going too far to say that at his best Bush’s drawings sometimes remind me of Michelangelo and Caravaggio?

No doubt such hyperbole is fostered by the tensions in Bush’s oeuvre between the tormented biography and the playful fantasy universe, between illustration and art, between the seamless commercial productions and the rough-edged sketches that seem to hover on another plane.