There is no doubt that Gustav Klimt engaged in sexual relationships with many women, including a large proportion of his favourite models. After his death no fewer than fourteen women came forward with claims for child support – four were accepted, of whom only Mizzi Zimmerman and Maria Ucicky are known to have been particularly important to Klimt. A double standard in his relationships with women was very definitely at work, where models were very much available for sex, but the upper and middle class women who were part of Klimt’s social and commercial circle were available only for platonic friendship, however strong the sexual urge might be.

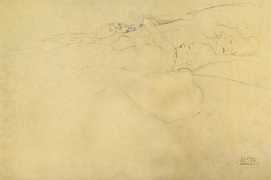

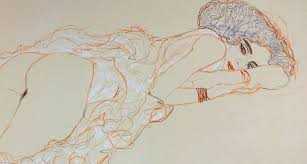

Klimt produced thousands of drawings and sketches during his productive years, every painting being preceded by dozens of preliminary sketches – to understand the importance of preliminary drawings to his masterworks it is well worth reading artist Chris Oatley’s blog posting, ‘The Gustav Klimt Drawings: Inside the Mind of a Master Draftsman’. As many as half of Klimt’s drawings were of naked women, mostly single but after around 1905 also in lesbian couplings and groups. The drawings shown here represent a tiny proportion of his output, and have been selected to show both the variety of poses that intrigued him and the skill with which these quick drawings were executed.

As you can imagine, Klimt’s relationships with women, and the role of women in his art, have been studied and commented on in minute detail. If you are interested in reading more, you could look at Klimt’s Women, a series of illustrated essays published in 2000 to accompany an exhibition in the Belvedere Gallery in Vienna, and The Naked Truth: Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka and Other Scandals, published in 2005 to accompany an exhibition of the same name at the Leopold Museum in Vienna. The best overall study of Klimt’s drawings is Rainer Metzger’s Gustav Klimt: Drawings and Watercolours, and below we have included a short extract from his introduction which explains something of the artist’s relationships with women, especially once he had established his reputation.

It was probably in around 1904 that Klimt began to keep a whole range of models at hand in his studio; very like a harem, there were always several of them in attendance in a special waiting room from where they could be called into the studio, ready for the man and master. It is not difficult to imagine that the atmosphere was a very unusual one, in which eroticism could be both a masculine drive for gratification and a source of artistic inspiration. Franz Servacs, a journalist and critic, wrote a memoir in 1918, shortly after Klimt’s death, which describes this setting with it provocative undertone of envy: in his studio ‘he was surrounded by mysteriously naked female creatures, who, while he stood silent in front of his easel, promenaded up and down his studio, lolled and lazed around and bloomed throughout the day – always ready for the master’s signal to remain obediently still as soon as he had glimpsed a pose or a movement that tantalised his sense of beauty enough to fleetingly capture it in a quick drawing’.

It was probably in around 1904 that Klimt began to keep a whole range of models at hand in his studio; very like a harem, there were always several of them in attendance in a special waiting room from where they could be called into the studio, ready for the man and master. It is not difficult to imagine that the atmosphere was a very unusual one, in which eroticism could be both a masculine drive for gratification and a source of artistic inspiration. Franz Servacs, a journalist and critic, wrote a memoir in 1918, shortly after Klimt’s death, which describes this setting with it provocative undertone of envy: in his studio ‘he was surrounded by mysteriously naked female creatures, who, while he stood silent in front of his easel, promenaded up and down his studio, lolled and lazed around and bloomed throughout the day – always ready for the master’s signal to remain obediently still as soon as he had glimpsed a pose or a movement that tantalised his sense of beauty enough to fleetingly capture it in a quick drawing’.

This atmosphere can be seen and felt most clearly in the many drawings in which Klimt conflates womanliness and femininity. These women are shown alone or in pairs, and they are completely self-absorbed. Klimt depicts them in various states of undress, as Servacs noted, but he also portrays them even more explicitly: as they masturbate and, as if it were completely incidental, lie with their thighs apart. They are always self-absorbed, but their availability, which they had to display as a matter of course in Klimt’s studio. is never revealed in these drawings. Everything was meant to seem as if these acts were the result of the most natural of drives and as if it were simply the intrinsic condition of woman to be centred on her own sexuality, deep in thought and lost in dreams. In contrast to the younger generation of Expressionists, Schiele and Kokoschka, Klimt himself is never present in these drawings. That he was most definitely present in the studio environment where these works were created is of course self-evident.

This atmosphere can be seen and felt most clearly in the many drawings in which Klimt conflates womanliness and femininity. These women are shown alone or in pairs, and they are completely self-absorbed. Klimt depicts them in various states of undress, as Servacs noted, but he also portrays them even more explicitly: as they masturbate and, as if it were completely incidental, lie with their thighs apart. They are always self-absorbed, but their availability, which they had to display as a matter of course in Klimt’s studio. is never revealed in these drawings. Everything was meant to seem as if these acts were the result of the most natural of drives and as if it were simply the intrinsic condition of woman to be centred on her own sexuality, deep in thought and lost in dreams. In contrast to the younger generation of Expressionists, Schiele and Kokoschka, Klimt himself is never present in these drawings. That he was most definitely present in the studio environment where these works were created is of course self-evident.

The viewpoint shown here is a masculine one, and it is here perhaps more than anywhere that this masculine gaze is clearly visible, accompanied by a naturalistic image of humankind. There is a turmoil here too: an insurmountable dependence on the hormonal and entirely physiological demands of the body. There are no signs of decay in these women’s bodies, yet they display weariness and unreadiness for life in every fibre of their abandon. The drawings draw their particular affirmative strength from the fact that it is the man and artist who has distilled attractiveness from their weariness and restored their lust for life through it charming lens of delicate suggestion. ‘We need do nothing, but eliminate the barrier between interior and exterior,’ Bahr advised his peers. The inner life of these women, as Klimt depicts it, is quite unambiguously the extension of their outer appearance.