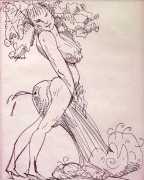

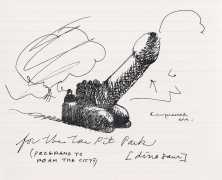

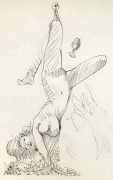

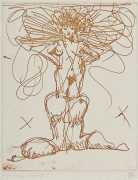

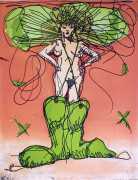

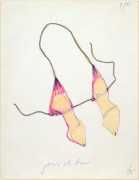

Claes Oldenburg’s sculptures made him one of the leading artists of pop art. He created objects that elevated the most mundane things – an unassuming light switch, a hamburger with a pickle on top, a clothes peg – to the status of high art. What he did stood out from the likes of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist because it was strange, crude, and downright funny. ‘I stand for art that entangles itself in everyday nonsense and yet comes out on top,’ Oldenburg wrote in a 1961 essay that resembles a manifesto. ‘I am for art that imitates human experience, comic if necessary, or cruel, or whatever. I am for art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists, elongates, accumulates, and breaks. It is heavy, rough, dull, sweet, and silly, like life itself.’

Claes Oldenburg’s sculptures made him one of the leading artists of pop art. He created objects that elevated the most mundane things – an unassuming light switch, a hamburger with a pickle on top, a clothes peg – to the status of high art. What he did stood out from the likes of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist because it was strange, crude, and downright funny. ‘I stand for art that entangles itself in everyday nonsense and yet comes out on top,’ Oldenburg wrote in a 1961 essay that resembles a manifesto. ‘I am for art that imitates human experience, comic if necessary, or cruel, or whatever. I am for art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists, elongates, accumulates, and breaks. It is heavy, rough, dull, sweet, and silly, like life itself.’

Oldenburg grew up in Stockholm, where his father was a Swedish diplomat. His early life was shaped by mobility, the family moving frequently before settling in Chicago in 1936. This exposure to different urban environments fostered a sensitivity not to monuments or ideals, but to the ordinary objects through which daily life is lived.

He studied literature and art history at Yale University from 1946 to 1950, before pursuing formal artistic training at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1950 until 1954. There he absorbed modernist principles, yet remained resistant to their emphasis on purity and abstraction. Early work as a reporter and illustrator further sharpened his attention to the textures of everyday life. By the late 1950s, after moving to New York, he became immersed in the city’s experimental downtown scene, collaborating with dancers, poets and performers.

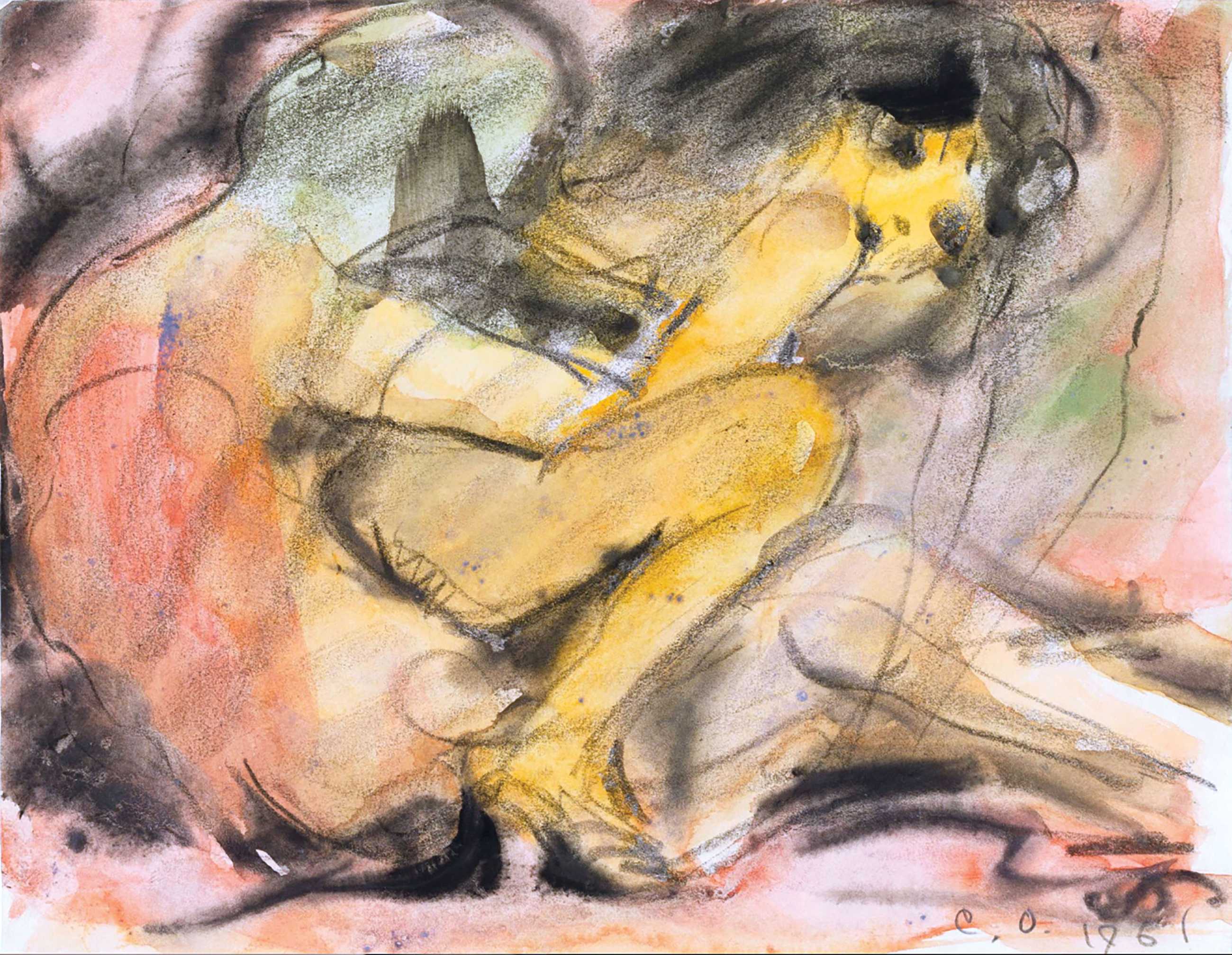

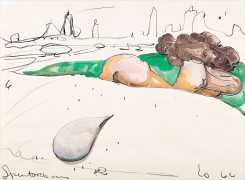

His personal life during this period was intense and unstable, marked by close relationships, domestic intimacy and emotional strain, experiences which fed directly into his work. Oldenburg’s early performances and soft sculptures from the early 1960s, produced with his wife Patty Mucha, transformed consumer goods into sagging, bodily forms suggesting vulnerability, desire and exhaustion.

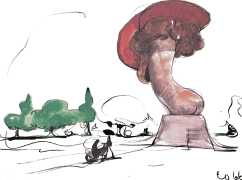

Oldenburg’s later partnership and marriage to Coosje van Bruggen, who he married in 1977, profoundly reshaped his practice. Van Bruggen provided intellectual rigour, architectural awareness, and collaborative balance. Together they produced the monumental public sculptures for which Oldenburg is best known, scaling up private obsessions without erasing their sensual or humorous undertones.

Throughout his career Oldenburg’s work reflected a belief that objects absorb human desire through use and attachment. His art remained grounded in lived experience – relationships, domestic spaces, and the body’s frailty. Always forthright in interviews, he described his life’s work sparingly – ‘A tiny sculpture can be just as powerful as a big one,’ he explained in a 2015 interview. ‘It’s all about imagination and fantasy, and that’s an integral part of my approach to art.’