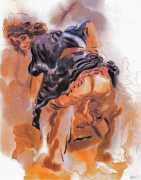

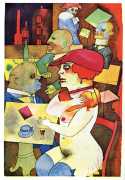

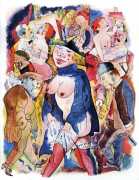

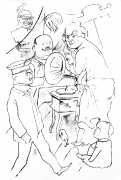

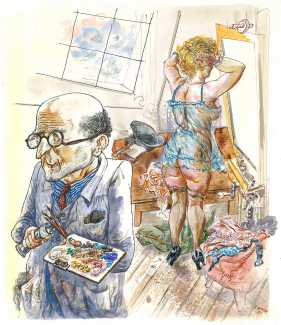

It is almost impossible to categorise the iconoclastic artist George Grosz’s work; the one thing that is certain is that his art was thoroughly impregnated with the sense of a society in disruption, and his uncompromising distinctive anarchistic style is unlike that of anyone else working in Germany during the turbulent years of the Weimar Republic. For Grosz it was unthinkable to be part of any organised, disciplined institution or movement. As well as liberating him from the kind of dogmatism that destroyed so many artists in the 1920s and 1930s, this meant he instinctively rooted his art in the common people and their lifestyles, habits and preoccupations.

It is almost impossible to categorise the iconoclastic artist George Grosz’s work; the one thing that is certain is that his art was thoroughly impregnated with the sense of a society in disruption, and his uncompromising distinctive anarchistic style is unlike that of anyone else working in Germany during the turbulent years of the Weimar Republic. For Grosz it was unthinkable to be part of any organised, disciplined institution or movement. As well as liberating him from the kind of dogmatism that destroyed so many artists in the 1920s and 1930s, this meant he instinctively rooted his art in the common people and their lifestyles, habits and preoccupations.

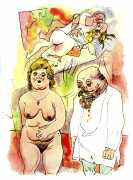

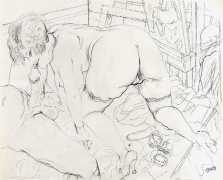

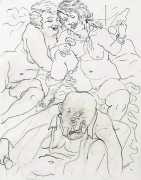

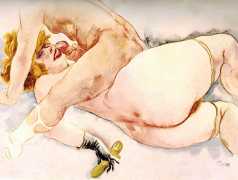

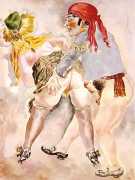

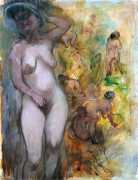

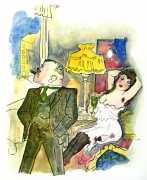

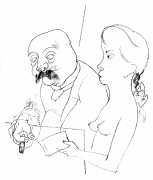

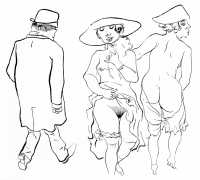

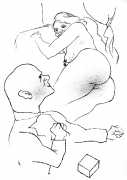

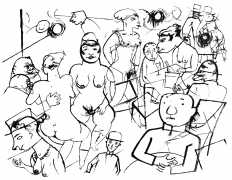

He was born Georg Ehrenfried Gross in Berlin, and studied at the Royal Academy of Art in Dresden. There he specialised in graphic art and started to contribute to satirical magazines as early as 1910. In 1913 he spent several months in Paris, the main subjects of his drawings of that period being orgies and other erotic subjects; he was a talented artist, and his drawings and paintings of the period are keenly observed and brilliantly executed.

He was born Georg Ehrenfried Gross in Berlin, and studied at the Royal Academy of Art in Dresden. There he specialised in graphic art and started to contribute to satirical magazines as early as 1910. In 1913 he spent several months in Paris, the main subjects of his drawings of that period being orgies and other erotic subjects; he was a talented artist, and his drawings and paintings of the period are keenly observed and brilliantly executed.

With the outbreak of the First World War he volunteered, but was discharged several months later. In 1916 he altered his name to George Grosz in protest against the growing tide of German nationalism, and collaborated with a group of authors, artists and intellectuals to found the Berlin Dada in 1917.

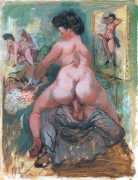

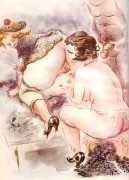

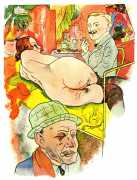

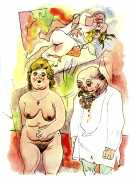

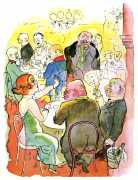

Following the revolution in Russia, Grosz became a member of the Communist Party, and in 1919, together with the publisher Wieland Herzfelde of Malik Publishing House started a magazine called Die Pleite (Bankruptcy); his drawings, fiercely critical of bourgeois society, appeared in various Malik publications including Ecce Homo in 1923, which was promptly banned as being pornographic.

Grosz’s satirical works of the 1920s were heavily influenced by the political and economical situation in post-war Germany. He himself wrote about that time: ‘Everywhere, hymns of hatred were being chanted. Everyone was hated: the Jews, the capitalists, the Junkers, the Communists, the army, the property owners, the workers, the unemployed, the black Reichwehr, the control commissions, the politicians, the department stores, and the Jews again. It was an orgy of incitement, and the republic itself was a weak thing, scarcely perceptible. It was a completely negative world, topped with colourful froth that many imagined to be true, happy Germany before the onset of the new barbarism.’

In 1932, invited to lecture to the Arts Student League in New York, Grosz visited the USA, and the following year emigrated there together with his wife and two sons. From 1937 to 1939 he was the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship, which enabled him to devote time to his own work. He was not rich, but he got by comfortably. In 1938 Grosz was stripped of his German citizenship, and many of his works were burnt by the Nazis. In 1959 Grosz eventually returned to Berlin, only to die a month later.