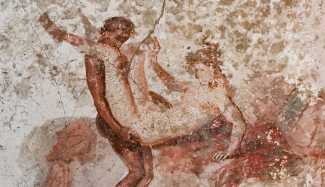

The first stirrings of the French Revolution in 1789 found Denon travelling widely in southern Europe, mostly in Italy, studying antiquities and spending a lot of time in Venice in the intimate company of one of the city’s most illustrious society women, Isabella Teotochi Albrizzi (1760–1836). Around this time he also visited the ruins of ancient Pompeii with its recently-discovered erotic wall paintings, and made the acquaintance of a French woman, Madame Mosion, whose physical attributes clearly stirred his sexual interest.

It was then that he heard that his French property had been confiscated, and his name placed on the list of the proscribed nobility. With characteristic courage he resolved to return to Paris, drop the ‘de’ from ‘de Denon’, and become a citizen of the republic; his situation was critical, but he was spared thanks mostly to the friendship of the painter David, who obtained for him a commission to create designs for republican costumes.

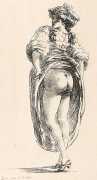

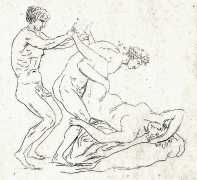

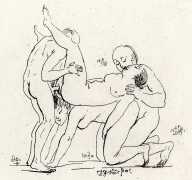

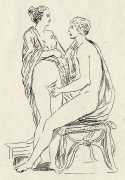

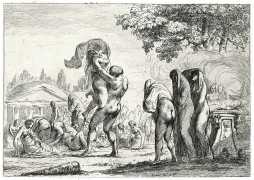

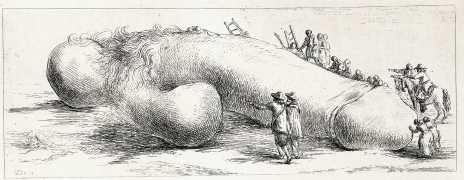

It was this period of existential decision-making which prompted the folio of engravings which quickly became known as L’oeuvre priapique (The Priapic Works), a miscellany of images loosely connected through their erotic nature. The first two are clearly aide-memoires of Madame Mosion’s physical attributes; of the rest some are sketches based on Pompeiian paintings, some erotic interpretations of classical themes, some fully worked and detailed engravings.

In her 1970 biography of Vivant Denon, Judith Nowinski discusses L’oeuvre priapique and its context; here is the relevant section:

Toward the end of his career, Vivant Denon created what he called ‘a lithographed autobiography’, expressed in terms of mythology: he portrayed himself at sixteen different ages, as the object of a tug of war between ‘love personified’ and ‘madness’. He found the desired relaxation by publishing a set of twenty-three engravings inspired by and depicting the sexual practices of the ancients in Pompeii.

The volume, entitled L’oeuvre priapique, appeared in 1793. The interest aroused by the work resulted in four letters to be found in the l’Intermediaire des Chercheurs et Curieux. From them we learn that the first edition was hard to come by; that the editor Barraud, 23 rue de Seine, had just re-edited the original pieces of Vivant Denon by including 27 prints of L’oeuvre priapique; that the 1793 volume had contained 23 plates. This must mean that Denon added later to his initial plates. Brunet mentions in his Manuel du Libraire that at the Delorme sale one copy of the rare album had sold for 98 francs. In another of the letters, we read that most of the works were signed ‘Denon, inv. et seul. 1793’, that one of them was dated 1787 and another 1790, and that a few were neither signed nor dated.

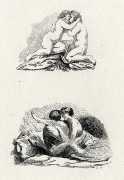

Portalis and Béraldi allowed themselves some conjectures based on a book which, to their mind, left no doubt regarding the laxity of Denon’s moral code. In it, they wrote, we find ‘the most voluptuous poses of Madame Mosion and the most licentious sexual fantasies known to lewd antiquity’. Of Madame Mosion, we are told that that ‘she had not been the most mistreated of women, nor Denon the least happy of lovers, judging by the beautiful portraits that he left us of her seductive person’. This woman, Jules-Maurice Renouvier contends, aroused in Denon an intense wish to depict the female body. He referred to one engraving done in 1784, and another, signed ‘Denon vidit et St. 1787’, in which she is portrayed ‘up to the waist, in the nude, seen in her most provocative hairstyle and in positions of abandon, from every angle, all executed with the artist’s lightest, most playful touch’.

The identity of Denon’s lovely friend has never been established, nor do we know whether he had met her in Naples, Rome, Paris, or in all three cities. As for the L’oeuvre priapique itself, it was considered erotic by some, pornographic by others, and scandalous by still others. For instance, Clément de Ris exclaimed that Point de lendemain was excusable, but that nothing could be said to justify the priapisms of Denon. ‘There are no two ways of evaluating such a work: it is pitifully worthless, but above all, it is a shameless act. I have said enough on this subject, and I ask that readers pardon me’.

The twentieth-century archaeological scholar, C.W. Ceram, considers Vivant’s group of etchings ‘brazenly phallic in concept’, and deplores our fragmented acquaintance with Vivant Denon; he asserts that those archaeologists whose writing mentioned Denon seemed unaware of his pornographic duplications. Also, Ceram continues, a learned cultural historian, Eduard Fuchs, in his History of Morals, included the Oeuvre priapique as a contribution to pornography without knowing that Denon had played an important role in the early days of Egyptology.