In 1944 Leonor Fini was asked to illustrate a new edition of the Marquis de Sade’s Juliette. She jumped at the opportunity; she already knew the text and was a great admirer of de Sade’s writings. She felt that as a woman she might have a new perspective on the book, and she was amused to learn that it was to be printed secretly on the Vatican presses at night.

De Sade had long been a hero to the surrealists for his demand for a free sexuality unrestrained by social custom; Hans Bellmer and Georges Bataille in particular were inspired by the excesses of de Sade’s novels.

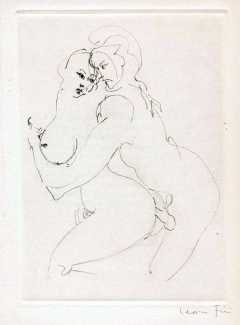

Of the women associated with surrealism, Leonor alone produced work that paralleled their cruel eroticism. Juliette was the powerful incarnation of feminine desire, as opposed to de Sade’s other heroine, the servile Justine, and Leonor makes her a vehicle for the expression of female dominance. She produced twenty-two drawings in a free-flowing, fluent style, not illustrative of specific incidents in the book but rather inspired by the atmosphere created by de Sade. These explicit scenes of sex and violence leave little to the imagination with their references to oral and anal sex and corporal punishment. Dismembered corpses are suspended from ropes or impaled on spikes, and the perpetrator of these deeds is shown with a death mask for a face.

Mario Praz loved these powerful images of the world of de Sade, and Alberto Moravia wrote admiringly ‘Not only has she recaptured that mixture of eighteenth-century grace and fury, of systematic cruelty and elegance, of reason and dream, that are proper to the author of Juliette, but she has also given the text an interpretation of her own, complete and free. The desperation and the sadness, the macabre pleasure and the unhealthy monotony of the mechanics of eroticism are represented with real force in these insatiable nudes, in these faces with their veils of black melancholy.’ Ten years later J.-R. Thomé wrote, ‘Nothing has been omitted by the illustrator of the most spectacular aspects of the infernal wedding of voluptuousness and death. What keeps the attention is more the intensity of the faces than the arrangement of the sexual positions.’

Leonor herself was happy with her images, but displeased that the book was published with photolithographs rather than original engravings, in order to save on expense. She retained her interest in de Sade, and later became friends with his specialist and biographer, Gilbert Lely, who presented her with a copy of his book La vie du Marquis de Sade of 1965 inscribed ‘to Leonor Fini, to her creatures of infernal spring, unique from age to age, to enslave the heart of men.’

Leonor went on to illustrate three of Gilbert Lely’s books, L’Épouse infidèle of 1966, Oeuvres poètiques of 1977, and Solomonie la possédée of 1979. When L’Épouse infidèle was published, she gave him a copy of the engraving from the book of a couple making love, which she inscribed ‘To my friend Gilbert Lely; The physical difference between man and woman, this fabulous luxury dazzles me’.

Leonor went on to illustrate three of Gilbert Lely’s books, L’Épouse infidèle of 1966, Oeuvres poètiques of 1977, and Solomonie la possédée of 1979. When L’Épouse infidèle was published, she gave him a copy of the engraving from the book of a couple making love, which she inscribed ‘To my friend Gilbert Lely; The physical difference between man and woman, this fabulous luxury dazzles me’.

Most of the text above is paraphrased from Peter Webb’s Sphinx: The Life and Art of Leonor Fini.

The Fini-illustrated edition of Juliette was published in ‘Rome’, and included representative passages of de Sade’s text followed by the plates; it was printed in an edition of 200 copies.