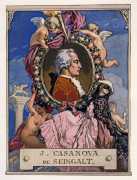

Almost everybody has heard of Casanova, the legendary eighteenth century Venetian adventurer who has become so famous for his often complicated and elaborate affairs with women that his name is now synonymous with ‘womaniser’. But few have read his complete memoirs, a touchingly honest account of a life from which, as he said of himself, ‘I am writing my autobiography to laugh at myself, and I am succeeding. I have loved women even to madness, but I have always loved liberty better. We ourselves are the authors of almost all our woes and griefs, of which we so unreasonably complain. I always willingly acknowledge my own self as the principal cause of every good and of every evil which may befall me; therefore, I have always found myself capable of being my own pupil, and ready to love my teacher.’

Almost everybody has heard of Casanova, the legendary eighteenth century Venetian adventurer who has become so famous for his often complicated and elaborate affairs with women that his name is now synonymous with ‘womaniser’. But few have read his complete memoirs, a touchingly honest account of a life from which, as he said of himself, ‘I am writing my autobiography to laugh at myself, and I am succeeding. I have loved women even to madness, but I have always loved liberty better. We ourselves are the authors of almost all our woes and griefs, of which we so unreasonably complain. I always willingly acknowledge my own self as the principal cause of every good and of every evil which may befall me; therefore, I have always found myself capable of being my own pupil, and ready to love my teacher.’

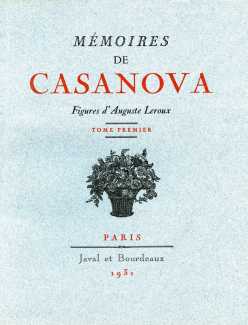

The 1920s saw a resurgence of interest in the life and exploits of Giacomo Casanova; a new complete multi-volume edition of his memoirs appeared in 1922 in English, published by the Casanova Society, and in German the complete Memoiren were published by Carl Henschel Verlag in 1925. Not to be outdone, the young Paris publishers Henri Javal and Pierre-Marie Bourdeaux decided that they would publish the most beautiful Casanova ever produced.

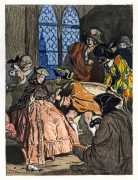

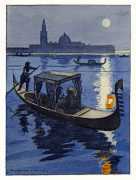

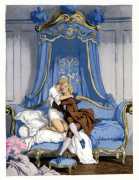

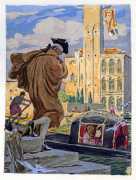

Auguste Leroux had already illustrated three Javal et Bourdeaux titles, including 1928 editions of Goethe’s Werther and Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Les liaisons dangereuses, when early in 1929 the two ambitious entrepreneurs suggested a new ten-volume Casanova with no fewer than two hundred colour illustrations.

The work involved was enormous. With all his other commissions and teaching commitments, it took Auguste Leroux nearly two years to deliver the artwork. Then plates needed to be made and proofed and the two thousand pages of text typeset and proofread, not to mention the marketing effort required to guarantee sales to cover the massive upfront costs. The first volumes finally appeared late in 1931, with the set not being completed until the summer of 1932.

Not surprisingly, Leroux produced very few book illustrations after Casanova, while Javal et Bourdeaux, the company’s funds much diminished, produced only cheap versions of classics like Baudelaire and Poe before going out of business late in 1933.

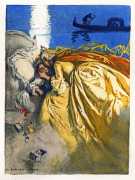

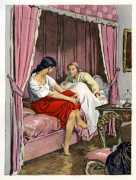

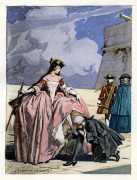

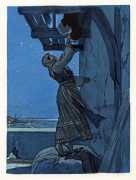

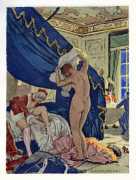

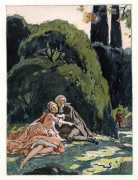

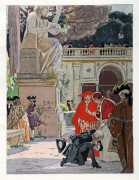

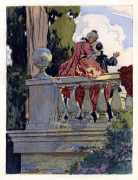

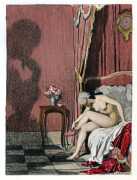

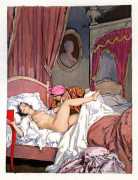

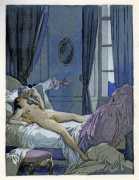

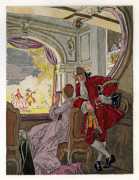

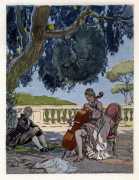

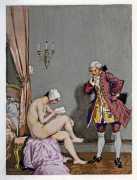

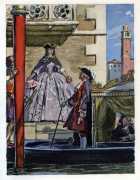

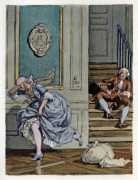

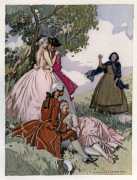

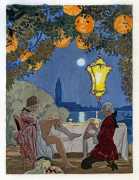

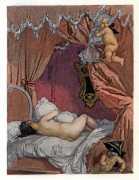

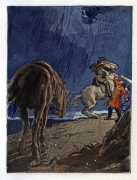

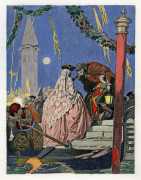

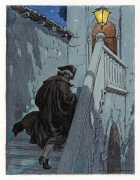

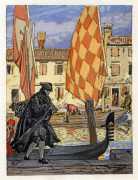

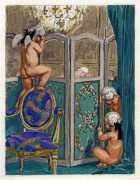

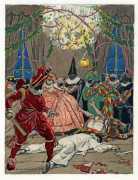

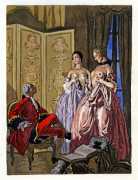

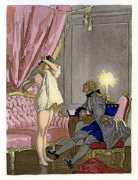

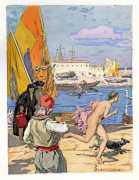

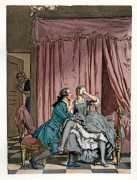

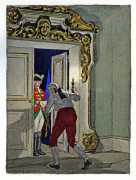

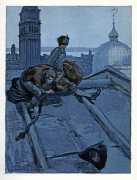

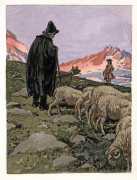

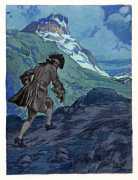

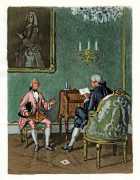

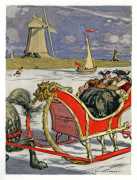

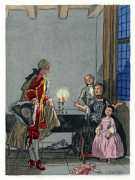

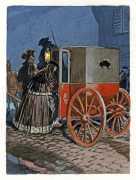

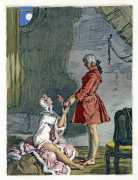

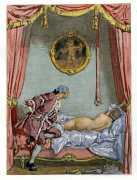

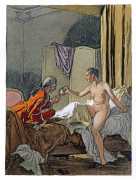

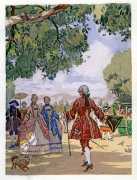

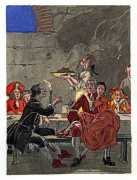

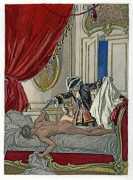

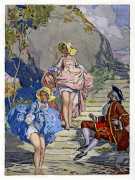

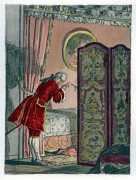

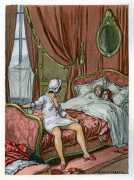

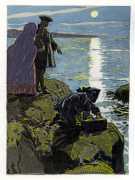

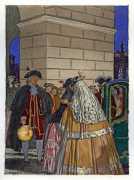

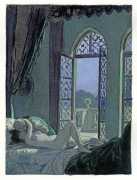

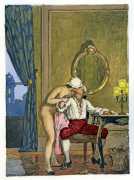

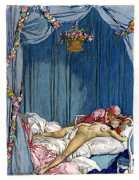

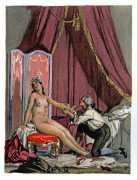

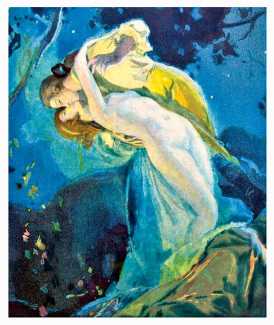

Having said that very few have actually read Casanova’s Memoirs, Leroux clearly did, his illustrations matching the text closely and intelligently. The perfectionist he was, every one of the two hundred images is carefully planned and executed, and the platemaker’s skill in reproducing his subtle colouring was rarely surpassed in the period. Leroux manages to convey the writer’s escapades without overlooking the many bedrooms and nakednesses involved, but always remains tasteful – as the French would say ‘galante’ rather than ‘libre’.

The Javal et Bourdeaux Casanova was published in ten volumes in a numbered limited edition of 2,350 copies.

The number of illustrations in this edition necessitates dividing them into two portfolios; the second, which follows directly after the first, can be found here.

There are free online texts available of the English-language version of the Casanova Memoirs (in the 1894 Arthur Machen translation rather than the more recent – and more accurate – ‘Brockhaus–Plon’ version). You can click here for the Gutenberg online version of the Machen translation.