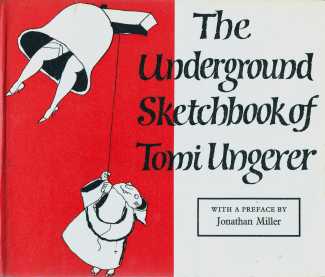

The Underground Sketchbook of Tomi Ungerer, published by the British publisher Bodley Head with an introduction by the (then) well-known theatre director and television presenter Jonathan Miller, was the first book-shaped compilation of Ungerer’s acerbic drawings.

The Underground Sketchbook of Tomi Ungerer, published by the British publisher Bodley Head with an introduction by the (then) well-known theatre director and television presenter Jonathan Miller, was the first book-shaped compilation of Ungerer’s acerbic drawings.

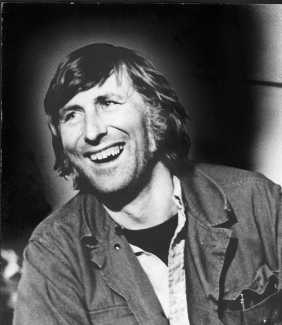

The world of Tomi Ungerer in New York in the 1960s is given colour and detail in a December 2014 Art in America article by Brooks Adams and Lisa Liebmann:

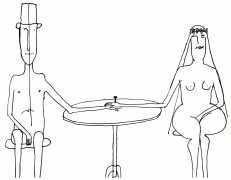

Throughout the sixties in New York, Tomi Ungerer lived high off the hog, rambunctiously so. He bought a house once belonging to Aaron Burr, in Greenwich Village, and had the bricks painted pink. He worked out of Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld’s lavish former offices overlooking Times Square. He drove a beige Bentley. And he continued to produce gleeful, vivid books for children, including The Three Robbers (1962), full of gorgeously saturated blacks, blues and reds; Orlando the Brave Vulture (1966), with its unlikely hero; the lyrical Moon Man (1967); and Zeralda’s Ogre (1967), a poignant Shrek precursor. But Ungerer’s pursuits, on and off the page, were various, and he proved a naughty boy himself.

He was married for the second time in 1959, to a young fashion editor soon to be known as the savvy food writer Miriam Ungerer, and found himself amid the city’s high-profile intelligentsia. Miriam urged him to do more reading in English. She hosted what was essentially a literary salon. He became friendly with Tom Wolfe, George Plimpton, Stanley Kubrick and Philip Roth. He designed a poster for Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove (1964). He rented an East Hampton retreat with Roth. He collaborated with Gunter Grass, whose first American edition (1961) of The Tin Drum includes Ungerer’s line illustrations. He hung out at Otto Preminger’s notorious film production office and attended famously wild parties at the director’s townhouse, leaving inscribed copies of his books for the presumably sleeping Preminger children.

He was married for the second time in 1959, to a young fashion editor soon to be known as the savvy food writer Miriam Ungerer, and found himself amid the city’s high-profile intelligentsia. Miriam urged him to do more reading in English. She hosted what was essentially a literary salon. He became friendly with Tom Wolfe, George Plimpton, Stanley Kubrick and Philip Roth. He designed a poster for Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove (1964). He rented an East Hampton retreat with Roth. He collaborated with Gunter Grass, whose first American edition (1961) of The Tin Drum includes Ungerer’s line illustrations. He hung out at Otto Preminger’s notorious film production office and attended famously wild parties at the director’s townhouse, leaving inscribed copies of his books for the presumably sleeping Preminger children.

It appears that Ungerer became an obstreperous trickster figure. He broke into empty weekend houses on Long Island, leaving behind trails of messed sheets and emptied glasses. He ignited a butane tank, which exploded, at one Hamptons backyard party, and stuck pebbles into uncooked meat patties at another—making ‘plenty of work for New York City dentists that summer’ as he recalled in an interview recently with a certain cheer.

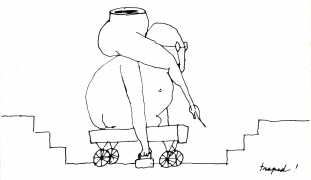

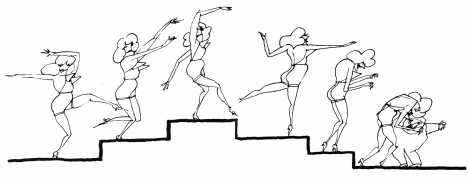

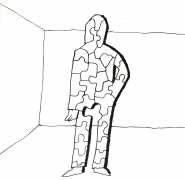

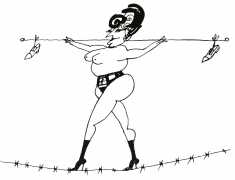

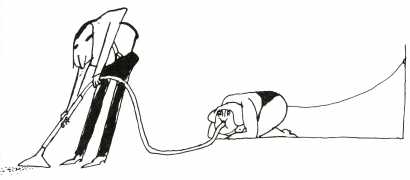

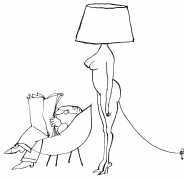

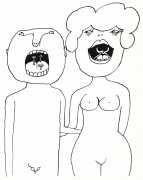

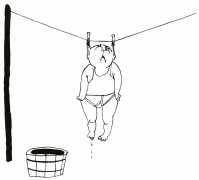

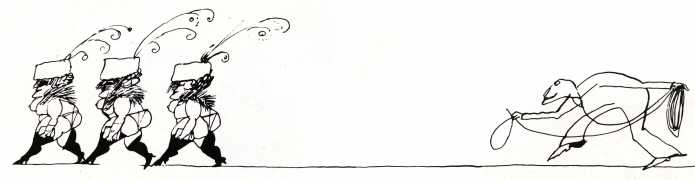

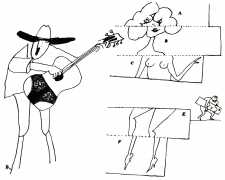

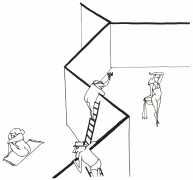

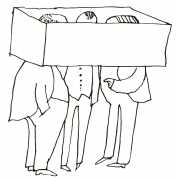

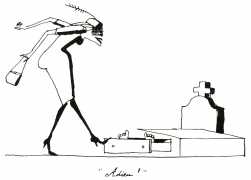

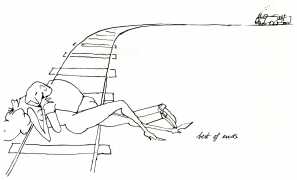

Graphically too Ungerer seemed to bite the hands that fed him, or at any rate gave him drinks. The Party (1966), a book of satirical drawings, imbues a famously liberal, urbane sixties milieu – the ‘radical chic’ scene, shortly avant la lettre – with some of the sulphurous outrage and flair for surreal grotesquerie that we may associate with George Grosz’s most scathing critiques.

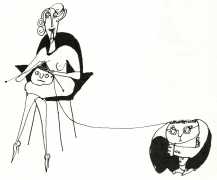

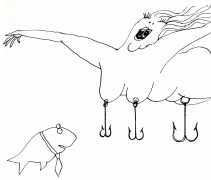

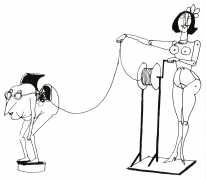

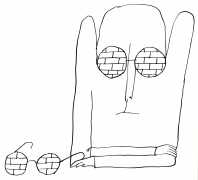

The Manhattan grotesques in Ungerer’s books do not really seem to mock any specific people, or address any specific horror or cause. They are representations of stock comic figures, endemic to the modern condition among ‘privileged classes’ pretty much since Molière – there's the praying-mantis-like socialite, the porcine banker, the effeminate roué. The mixture in these drawings of abundant talent, an obvious lack of social insight or nuance, and overwrought allegorising – rats, for instance, seen scrambling into the eye sockets of one portly partygoer – makes for a paradoxically flat viewing experience. Ungerer does not have a satirist’s eye for the killer detail – unlike, say, Jessica Craig-Martin, whose rueful, devastating photo-portraits of latter-day benefit-circuit doyennes (those ferocious and bejeweled aging hands!) were taken during recent social seasons-in-hell.

Yet the drawings are indeed as virtuosic as Grosz’s, perhaps more so. Ungerer is in a league with such prodigiously gifted and stylistically varied artists of roughly his own generation as Larry Rivers and Jim Dine. As for his penchant for the fantastical and the macabre, one has but to look to the many masters he copied in his youth, luminaries of the Northern Renaissance, including Hans Baldung Grien and Matthias Grünewald, whose Isenheim Altarpiece resides in Colmar, across the street from the bus stop where Ungerer used to wait to be taken to school.

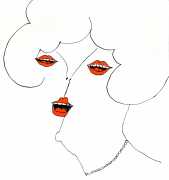

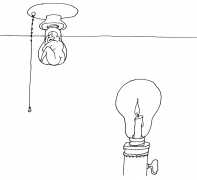

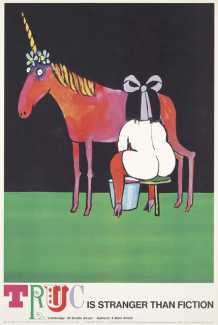

Soon after creating the cocktail party critiques, Ungerer produced some of his very best work, most of it geared to mass communication and commerce. There were ad campaigns for both the New York Times and the Village Voice. There is a clever and saucy poster for the legendary nightclub Electric Circus that has a delicate style denoting an irreverent nod to Saul Steinberg, another of Ungerer’s masters, albeit a contemporary one. There is a charming 1968 poster for Truc, a cult boutique in Cambridge, Mass., wherein a cherubic lady, naked but for a hair ribbon and stockings, is milking a unicorn, with the caption ‘Truc is stranger than fiction’. Ungerer's posters for a 1968 ad campaign promoting the Village Voice are period classics to rival Milton Glaser’s famous 1967 poster for Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits, an Aubrey Beardsley-esque silhouetted profile of Dylan with multicoloured, hyper-stylised hair.

Soon after creating the cocktail party critiques, Ungerer produced some of his very best work, most of it geared to mass communication and commerce. There were ad campaigns for both the New York Times and the Village Voice. There is a clever and saucy poster for the legendary nightclub Electric Circus that has a delicate style denoting an irreverent nod to Saul Steinberg, another of Ungerer’s masters, albeit a contemporary one. There is a charming 1968 poster for Truc, a cult boutique in Cambridge, Mass., wherein a cherubic lady, naked but for a hair ribbon and stockings, is milking a unicorn, with the caption ‘Truc is stranger than fiction’. Ungerer's posters for a 1968 ad campaign promoting the Village Voice are period classics to rival Milton Glaser’s famous 1967 poster for Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits, an Aubrey Beardsley-esque silhouetted profile of Dylan with multicoloured, hyper-stylised hair.

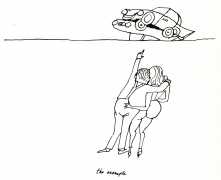

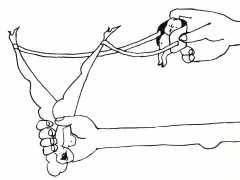

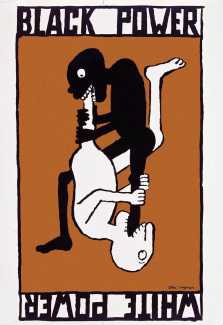

Ungerer’s anger found apt expression in the later part of the decade. When in 1967 a consortium of Columbia University teachers and students rejected a series of seven anti-Vietnam-War posters they had commissioned from him (‘too virulent’ was their verdict), he published them himself, and they found their way into countless dorm rooms nevertheless. Several of these involve images of the Statue of Liberty, a monument created by Frédéric Bartholdi, a Colmar native. In Eat, a diminutive Liberty is being rammed down the throat of a crudely rendered Asian figure; in Kiss for Peace, our Lady of the Harbor is having her ass licked frantically – by another Asian figure. A different poster in the series, of US aircraft dropping gift-wrapped ‘presents’ intermingled with ‘duds’, may remind some viewers of Nancy Spero’s thematically similar but far more ethereal antiwar imagery. Ungerer also published his own hard-hitting posters on the subject of race relations: Black Power/White Power, the best-known of these, shows two emblematic figures in a ‘69’ position, each devouring the other’s phallic leg.

Ungerer’s anger found apt expression in the later part of the decade. When in 1967 a consortium of Columbia University teachers and students rejected a series of seven anti-Vietnam-War posters they had commissioned from him (‘too virulent’ was their verdict), he published them himself, and they found their way into countless dorm rooms nevertheless. Several of these involve images of the Statue of Liberty, a monument created by Frédéric Bartholdi, a Colmar native. In Eat, a diminutive Liberty is being rammed down the throat of a crudely rendered Asian figure; in Kiss for Peace, our Lady of the Harbor is having her ass licked frantically – by another Asian figure. A different poster in the series, of US aircraft dropping gift-wrapped ‘presents’ intermingled with ‘duds’, may remind some viewers of Nancy Spero’s thematically similar but far more ethereal antiwar imagery. Ungerer also published his own hard-hitting posters on the subject of race relations: Black Power/White Power, the best-known of these, shows two emblematic figures in a ‘69’ position, each devouring the other’s phallic leg.

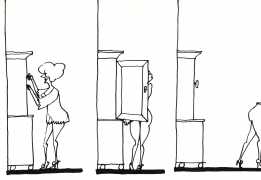

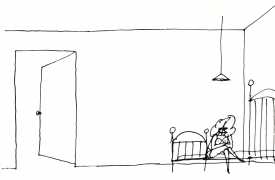

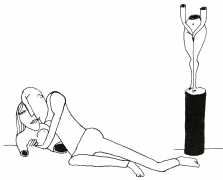

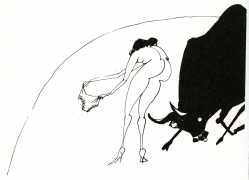

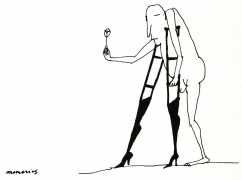

As the mood of the sixties darkened, so too it seems did Ungerer’s life and work. The Ungerers had a daughter in 1961, but their marriage dissolved before the end of the decade. Ziegfeld’s Times Square aerie gave way to redevelopment. Ungerer sold the pink house (this, interestingly, seems to have occasioned his one direct encounter with Andy Warhol, who came to look at it with his mother; was the Factory scene too swish for this swashbuckler?) He got himself a garçonnière (a bachelor pad), and along with it – truc is stranger than fiction – a volunteer female ‘sex slave’ to live in it with him for a while: Ungerer claims that reading Pauline Réage’s Story of O (1954) ‘changed my life’.