It was originally Sylvain Sauvage’s intention to produce illustrations to the whole of Casanova’s memoirs, but he no doubt quickly realised that at more than three thousand pages the task was more than he could manage. So he settled on the relatively short and well-known story of Casanova and the Nun of Murano, and sensibly titled it the singular Une aventure de Casanova.

It was originally Sylvain Sauvage’s intention to produce illustrations to the whole of Casanova’s memoirs, but he no doubt quickly realised that at more than three thousand pages the task was more than he could manage. So he settled on the relatively short and well-known story of Casanova and the Nun of Murano, and sensibly titled it the singular Une aventure de Casanova.

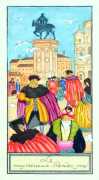

Casanova’s life was transformed when, at just twenty-one years old, he saved a wealthy Venetian senator after an apoplectic fit. The grateful noble, Don Matteo Bragadin, adopted the charismatic young man and showered him with funds, thus allowing him to live like a playboy aristocrat, wear fine clothes, gamble and conduct high society affairs. The few descriptions and surviving portraits of Casanova confirm that in his prime he was an imposing presence, over six feet tall. ‘My currency was an unbridled self-esteem,’ Casanova noted in his memoir of his youthful self, ‘which inexperience forbade me to doubt.’

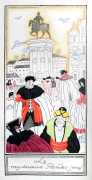

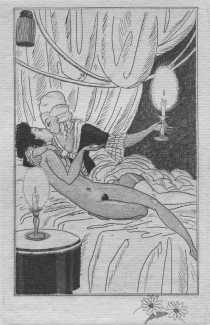

Few women could resist. One of his most famous seductions was of a ravishing, noble-born nun he identifies only as M.M. (historians have identified her most likely as Marina Morosini). Spirited by gondola from her convent on the island of Murano to a secret luxury apartment, the young lady ‘was astonished to find herself receptive to so much pleasure,’ Casanova recalls, ‘for I showed her many things she had considered fictions, andI taught her that the slightest constraint spoils the greatest pleasures.’ The long-running romance blossomed into a ménage à trois when M.M.’s older lover, the French ambassador, joined their encounters, then to à quatre when they were joined by another young nun, C.C. (most likely Caterina Capretta).

The first version of Sauvage’s Une aventure de Casanova, histoire complète de ses amours avec la belle C.C. et la religieuse de Muran (An adventure of Casanova, a full account of his love affairs with the beautiful CC and the nun of Muran) consisted of twenty full-page plates and thirteen smaller ones, in a large-paper edition of 75 copies published ‘Chez l’artiste’, the artist’s home at 16 rue Cassini, not far from the Luxembourg Gardens. Ever the perfectionist and experimenter, he worked with his printer Paul Haasen and the typographers Frazier-Soye to produce an original and high-quality portfolio. This portfolio appeared in late 1920 and was quickly subscribed and sold.

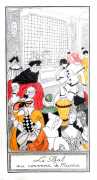

Over the next four years he collaborated with the Paris publisher Paul Cotinaud to produce new and expanded versions of Une aventure de Casanova. In 1924 Cinquante eaux-fortes de Sylvain Sauvage pour illustrer les mémoires de Jacques Casanova de Seingalt Venetien (Fifty watercolours illustrating the Memoirs of the Venetian Jacques Casabova de Seingalt) appeared, followed soon after by a portfolio of twelve ‘planches refusées’, slightly more risqué images for more discerning and deep-pocketed collectors. Like the fifty-plate portfolio, this was produced in a numbered edition of 150 copies.

Finally, in 1926, Sauvage and Cotinaud produced a cheaper two-volume edition of Casanova in Cotinaud’s ‘La rose mal défendue’ (The Poorly-Defended Rose) series. This edition included all the original plates in their black-only version, though several coloured versions exist, some thought to be coloured by Sauvage for special clients and some by those clients themselves. This edition was produced in a numbered edition of 75 large-paper copies, 18 specials for ‘collaborateurs’, and 450 standard copies.

Here we show all of the illustrations from the 1926 edition, plus a selection of colour versions from the 1920 edition and three of the twelve ‘planches refusées’; if anyone can help us add the others we would love to hear from you.