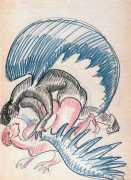

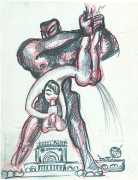

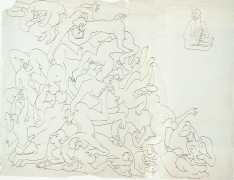

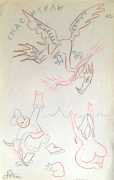

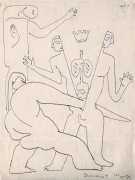

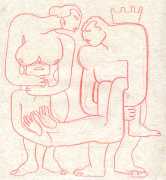

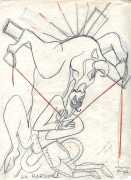

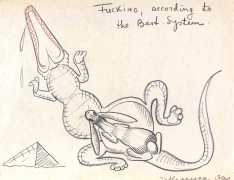

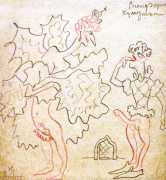

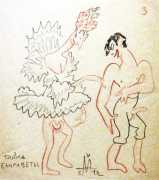

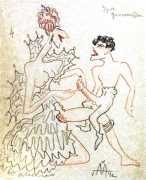

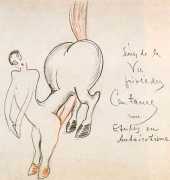

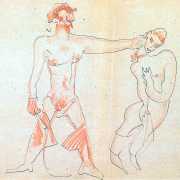

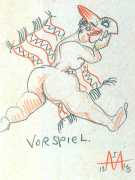

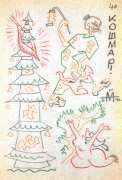

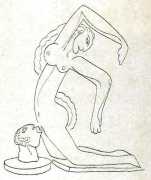

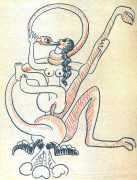

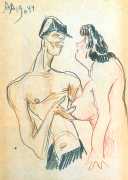

It is not common knowledge that as well as film-making, Sergei Eisenstein also excelled at drawing, and though he described himself as asexual, there is no doubt from his artistic output that sex fascinated him. His erotic works are funny, playful, dynamic, provocative, and incredibly inventive. Works done in 1931, shortly after his arrival in Mexico, display the muscular, energetic bodies of toreadors, horses and bulls, merged in the orgiastic union of death and sex. The style of fleshy, robust figures represented with thick lines made by a dark pencil with red shading resembles that of Mexican muralists, José Clemente Orozco in particular. As Maria Haltunen has noted in her dissertation devoted to Eisenstein’s erotic drawings, the film-maker’s trip to Mexico opened his eyes to that country’s culture, replete with the images of ancient pagan myths blended with Catholicism. For the artist, the powerful merging of corporeality, death, and sexually charged mythology stimulated a search for new visual symbols of this baroque visuality. The influence of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic writings, especially his book on Leonardo da Vinci, directed Eisenstein’s thoughts toward the unconscious and the fundamental role of sexuality in the constitution of the human psyche. Among the drawings done in Mexico, there is a group of works lampooning the Catholic church and its missionary intervention there as that of an invasion of sexual perverts into the virgin land of indigenous cultures.

It is not common knowledge that as well as film-making, Sergei Eisenstein also excelled at drawing, and though he described himself as asexual, there is no doubt from his artistic output that sex fascinated him. His erotic works are funny, playful, dynamic, provocative, and incredibly inventive. Works done in 1931, shortly after his arrival in Mexico, display the muscular, energetic bodies of toreadors, horses and bulls, merged in the orgiastic union of death and sex. The style of fleshy, robust figures represented with thick lines made by a dark pencil with red shading resembles that of Mexican muralists, José Clemente Orozco in particular. As Maria Haltunen has noted in her dissertation devoted to Eisenstein’s erotic drawings, the film-maker’s trip to Mexico opened his eyes to that country’s culture, replete with the images of ancient pagan myths blended with Catholicism. For the artist, the powerful merging of corporeality, death, and sexually charged mythology stimulated a search for new visual symbols of this baroque visuality. The influence of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic writings, especially his book on Leonardo da Vinci, directed Eisenstein’s thoughts toward the unconscious and the fundamental role of sexuality in the constitution of the human psyche. Among the drawings done in Mexico, there is a group of works lampooning the Catholic church and its missionary intervention there as that of an invasion of sexual perverts into the virgin land of indigenous cultures.

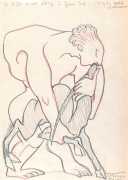

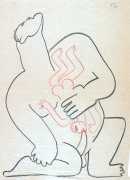

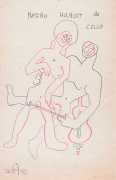

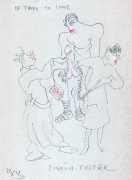

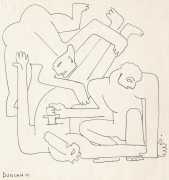

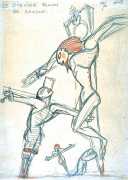

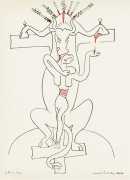

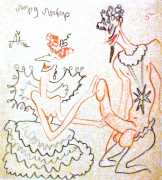

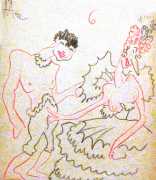

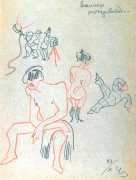

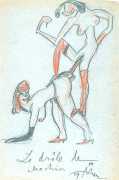

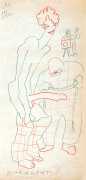

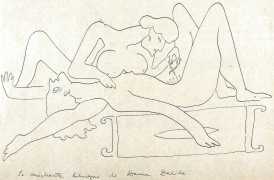

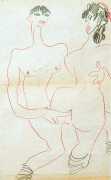

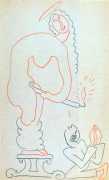

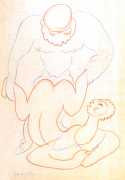

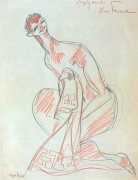

Drawings done after Eisenstein’s return to the Soviet Union are no less provocative than the Mexican ones, but they are more sparsely articulated. Here, male and female figures copulate in astounding positions and circumstances, from being penetrated by plant-like forms to enthusiastically celebrating what looks like a sadistic orgy with cut bellies, pools of blood and other shocking sights of debauchery. In these later works, Eisenstein used line only, minimising shading and the volumetric shaping of figures. Among them we find two sketches for an unrealised film on Alexander Pushkin; several done during the filming of Ivan Grozny; and a series that appears to have been inspired by George Grosz’s images of maimed war veterans. While Eisenstein’s line drawings display his skill in imitating many well-known artists of the day, including Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau and Léon Bakst, in the composition and arrangements of figures, references to Grosz (whom he met during one of his trips to Europe) are more specific. Officers in full uniform, and lame war cripples, distinguished by characteristic decorations on their chests, engage in what appear to be male homosexual acts, with men either donned in cross-dressing paraphernalia and enjoying glasses of champagne or attempting to figure out how to engage in sex while missing multiple limbs.

According to Joan Neuberger, a historian who has studied Eisenstein’s life and career, there are more than 5,000 of these works with widely varied subjects: ‘Some of these drawings are connected with specific films; some are related to his reading or thinking; some are portraits of the people he saw or places he visited; and some depict people (and animals and various anthropomorphised features of sexual anatomy) having sex.’ After Eisenstein’s death, his widow, Pera Atasheva, gave most of his drawings to the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art. Atasheva kept a relatively small cache of about 500 drawings that had sexual subject matter, because she feared that they might be considered harmful to the film-maker’s legacy. Later, she passed them for safekeeping to Andrei Moskvin, a cameraman who had worked with Eisenstein on the filming of Ivan Grozny. After perestroika, Moskvin’s descendants sold the drawings to a private collector in the west.

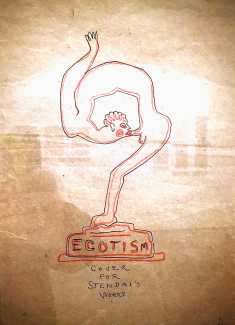

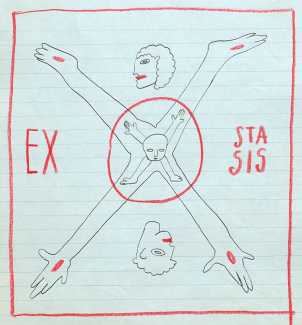

Despite Atasheva’s fear of these works being censored by Soviet authorities, and at least one instance of their near confiscation as pornography, notably at the US border during the film-maker’s return from Mexico, scholars unanimously agree that the drawings have been done for aesthetic reasons and, as such, stand exempt from the charges of societal transgression. In his 1946 text How I Learned to Draw (A Chapter about My Dancing Lessons), Eisenstein told the story of the first drawing made for him by an adult in a space that was used for dancing lessons. The fact that ‘the line was a track left by a movement’ left a lasting impression on him. As the art critic Annette Michelson noted in her essay about the film-maker, the link between dance and drawing emerged in the notion of the ecstatic, which Eisenstein developed in his writing towards the end of his life. For him ‘Exstasis’ was characterised by ‘being beside oneself’ in a pictorial sense, meaning that by ecstasy, Eisenstein means not the person’s behaviour, but the aesthetic principal of excess achieved by formal means. He drew constantly and instantaneously, filling pieces of paper with imaginary scenes that would bring the viewer ‘beside himself’. The subject of his sex drawings – scenes of sexual excess or transgression – was one that could achieve this effect, and so it was used to this end. For Eisenstein drawing was a means to develop a visually effective language, which he applied in his work as film director. His drawings demonstrate the power of the expressive representational language of art, teaching us to distinguish art from pornography.

Despite Atasheva’s fear of these works being censored by Soviet authorities, and at least one instance of their near confiscation as pornography, notably at the US border during the film-maker’s return from Mexico, scholars unanimously agree that the drawings have been done for aesthetic reasons and, as such, stand exempt from the charges of societal transgression. In his 1946 text How I Learned to Draw (A Chapter about My Dancing Lessons), Eisenstein told the story of the first drawing made for him by an adult in a space that was used for dancing lessons. The fact that ‘the line was a track left by a movement’ left a lasting impression on him. As the art critic Annette Michelson noted in her essay about the film-maker, the link between dance and drawing emerged in the notion of the ecstatic, which Eisenstein developed in his writing towards the end of his life. For him ‘Exstasis’ was characterised by ‘being beside oneself’ in a pictorial sense, meaning that by ecstasy, Eisenstein means not the person’s behaviour, but the aesthetic principal of excess achieved by formal means. He drew constantly and instantaneously, filling pieces of paper with imaginary scenes that would bring the viewer ‘beside himself’. The subject of his sex drawings – scenes of sexual excess or transgression – was one that could achieve this effect, and so it was used to this end. For Eisenstein drawing was a means to develop a visually effective language, which he applied in his work as film director. His drawings demonstrate the power of the expressive representational language of art, teaching us to distinguish art from pornography.

We are very grateful to Hans-Jürgen Döpp in Frankfurt and to Yuri in Moscow for sharing these images with us.