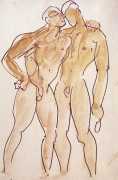

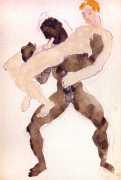

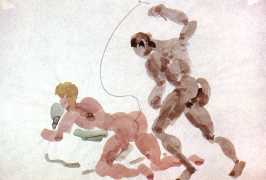

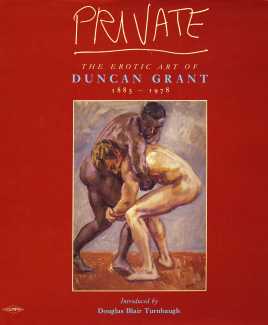

In 1989 The Gay Men’s Press brought together the largest collection of Duncan Grant’s homoerotic work that had been seen together in a volume titled Private, with an extensive and informative biographical and contextual introduction by the writer and film producer Douglas Blair Turnbaugh. Turnbaugh’s text remains the best introduction to Grant’s erotic work, explaining that ‘Through his art, Duncan Grant bequeathes to anybody with liberated common sense this legacy of interpretation of his consciously personal, original experience. What incredible power these fragile, vulnerable images hold for us today. It is a legacy of optimism and hope in time of despair. Duncan uses allegory, metaphor, thought, reality and fantasy to make his statements, but he never uses them to protect himself, and he certainly never uses a figleaf or posing strap as a concession to the bowdlerisers. In Duncan’s work, there is no code to break.’

In 1989 The Gay Men’s Press brought together the largest collection of Duncan Grant’s homoerotic work that had been seen together in a volume titled Private, with an extensive and informative biographical and contextual introduction by the writer and film producer Douglas Blair Turnbaugh. Turnbaugh’s text remains the best introduction to Grant’s erotic work, explaining that ‘Through his art, Duncan Grant bequeathes to anybody with liberated common sense this legacy of interpretation of his consciously personal, original experience. What incredible power these fragile, vulnerable images hold for us today. It is a legacy of optimism and hope in time of despair. Duncan uses allegory, metaphor, thought, reality and fantasy to make his statements, but he never uses them to protect himself, and he certainly never uses a figleaf or posing strap as a concession to the bowdlerisers. In Duncan’s work, there is no code to break.’

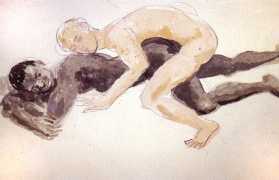

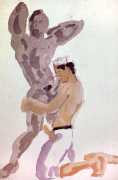

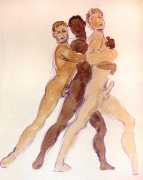

As a postscript to the Private collection, in October 2020 an extraordinary stash of more than four hundred erotic drawings by Duncan Grant, long thought to have been destroyed, came to light. It had secretly been passed down over the decades from friend to friend and lover to lover. In May 1959 Grant gave his friend Edward le Bas a folder marked ‘these drawings are very private’, and the story in Bloomsbury circles was that the drawings had been destroyed, probably by Le Bas’s sister. However, it turned out that Le Bas had given them to the gay gallery owner Eardley Knollys, who when he died in 1991 left them to Mattei Radev, a Bloomsbury mainstay who as a younger man had had a secret, tortured affair with E.M. Forster. Radev then became the partner of theatre designer Norman Coates, who for years stored the drawings in plastic folders under his bed.

Rather than sell the collection on the open market, Coates generously offered them to The Charleston Trust, explaining that ‘They need to be kept together, a body of work that talks of love. Of course at a time they were made it was a love that was illegal, so he was never able to share the works. How we see them now will be very different.’