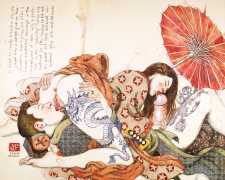

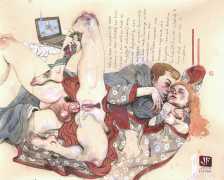

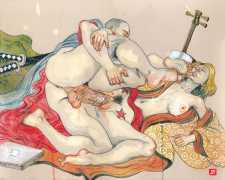

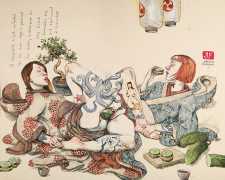

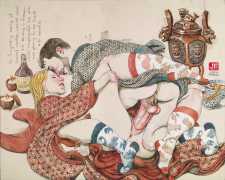

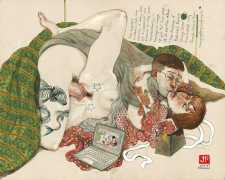

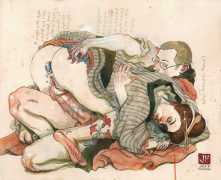

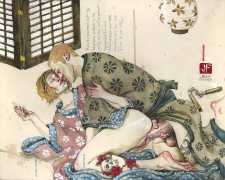

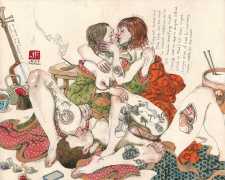

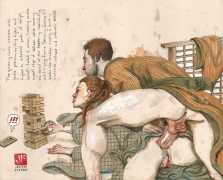

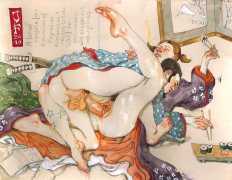

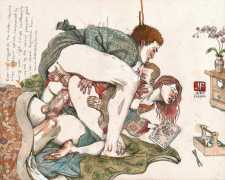

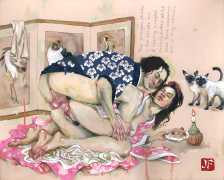

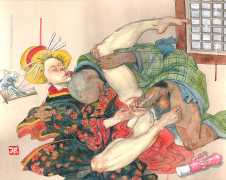

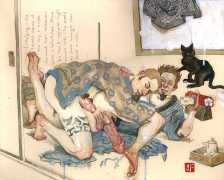

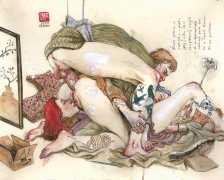

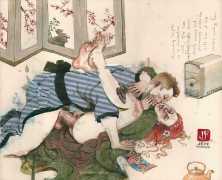

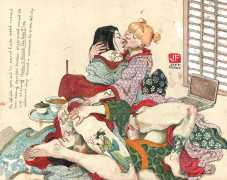

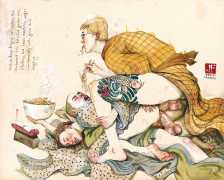

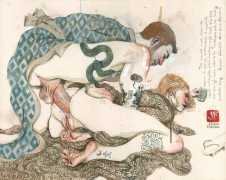

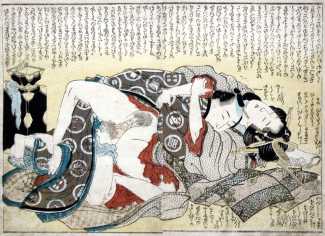

Reaching its climax in the Edo period, from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, the Japanese erotic art genre of Shunga was created using woodblocks. Japanese masters of the form include Katsushika Hokusai, Kitagawa Utamaro and Utagawa Kunisada. Shunga prints, though undeniably sexual, favoured the strange and the silly as much as the romantic, featuring ornate robes, lots of pubic hair, massively enlarged penises, imaginative sex positions – and the occasional octopus.

In Jeff Faerber’s contemporary versions of Shunga, sexual partners with many piercings and tattoos flaunt blatantly engorged genitalia. Japanese robes, printed screens, sushi and tea sets, paying homage to the original prints, while the dildos, cell phones and computers bring the imagery solidly into the twenty-first century. The explicit images, hilariously endowed with titles like ‘They discussed Chaucer, supped on ’89 Vieux Château Certan with hints of blackcurrant and elderberry, then topped the evening off with a wee bit of bumfuckery and tea’, and ‘In order to remedy a humdrum day, she jumped onto a usenet group on the information superhighway, and after a fulsome substantive exchange in the market place of ideas with a gentleman on the lickylicky forum, she contrived an IRL session to try out his wares and thus attained unhindered glory with oral delicacies’, present a light-hearted interpretation of how the erotic is portrayed and practised, then and now, in East and West.

Jeff Faerber explains, ‘I’ve been a huge fan of Japanese woodblock prints for as long as I can remember, including shunga as well as samurai battling monsters, quiet landscapes, or the iconic Hokusai wave and mountain print. Something about their line quality and flat, limited colours reminds me of superhero comics from my youth. The Japanese Shunga prints, of course, have the added titillation factor and Incredible Hulk-sized hero phalluses which make them particularly memorable. I find it interesting that when the Shunga prints were produced, the artists’ contemporaries viewed them as low-brow pornography, and many of the artists had noms d’artistes to protect their reputations for their mainstream work. Yet today Shunga can be seen in mainstream art galleries and respectable coffee-table books. Somehow societies view contemporary expressions of sex as distasteful, but when aged by a century or two suddenly these works can be viewed in polite society. I look forward to the twenty-second century, where my work will finally be viewed as important and acceptable.’