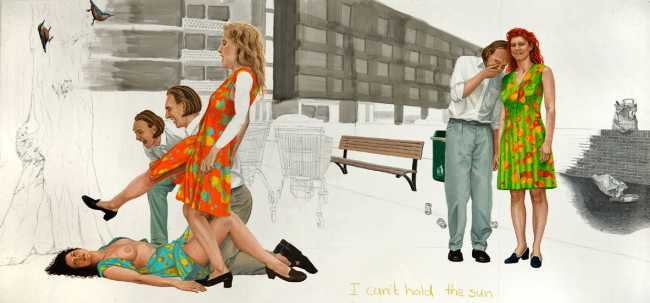

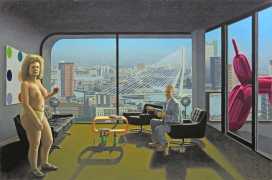

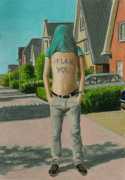

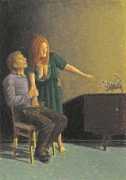

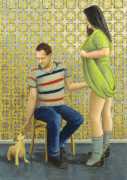

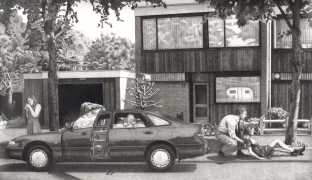

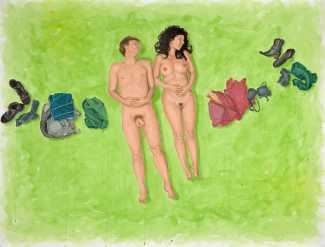

Absolutely Maybe (Absoluut Misschien) was the title of a major exhibition of Jans Muskee’s paintings held at the Drents Museum in Assen in 2018, featuring some of the best of his work from the previous thirty years. The seemingly contradictory title neatly encapsulates the mismatches in his ultrarealistic pastel drawings, in which the neat world of family life in Ikea homes clashes with undercurrents of fantasy and desire. Once seen, the tensions are hard to unsee.

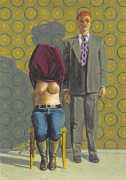

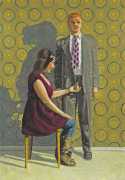

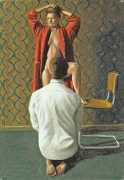

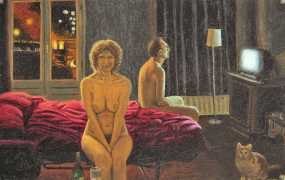

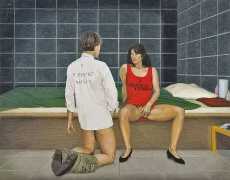

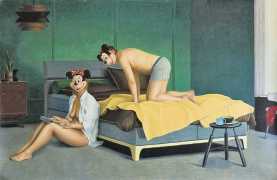

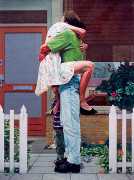

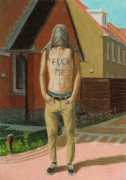

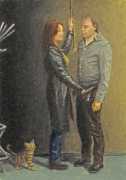

Muskee uses his life-size drawings to expose a world that is not intended for our eyes. His canvases encourage the viewer to take on the role of voyeur, simultaneously attracted and repulsed. The people depicted in his lifesize drawings do things that are not normally intended for our eyes, and because they are actual size it is as though the viewer is present at the events being displayed, and made complicit in their activities. Muskee creates a contact with the viewer that the people in his drawings rarely seem to have among themselves. This inability of people to make real contact is one of the main themes in his work. What hides behind an apparently everyday cheerfulness is a world of unfulfilled desires, sexual fantasies and restrained emotions.

Meta Knol, Director of De Lakenhal gallery in Leiden, has written an interesting analysis of Muskee’s works titled The Misunderstanding of Jans Muskee, which you can read in full on Muskee’s website here. This extract gives an excellent overview:

The fate that Oedipus will undergo is inevitable. The curse of his father rests upon him, and without knowing it he murders his father, marries his mother, copulates with her, and begets four children. Then comes the moment of truth. Jocasta, his mother, wife and lover, hangs herself in their bedroom. Oedipus discovers her body, realizes what has happened, and puts out both his eyes. For the rest of his life he wanders in darkness, a fugitive, homeless and outlawed. Guilty as hell. Or not?

The classics are not particularly kind to us, and certainly not in the context of sex, violence, pain, and double-crossing. In comparison to the heroes of Sophocles, the characters in Jans Muskee’s drawings are very commonplace, almost colourless. So why are these drawings so distressing? Why is it so much more disturbing to view a drawing by Muskee than it is to read an old myth, a dirty novel, or a topical news article?

Although Muskee usually restricts himself to the exact reproduction of visual reality, the drama that lurks under the surface is painfully obvious in his drawings. There is a reality that you do not see behind the façade. The drawings are carefully staged, the events are placed in a sharp theatrical light, and they reveal precisely what you are not supposed to see: frustrations, obsessions, pain, guilt, anxiety, and incapacity. Jans Muskee shows us the naked truth, in all its lousy triviality. He reproduces the cool facts.

In their commonplace, everyday literalism, the characters in Jans Muskee’s drawings are artificial and unreal. They are thrown back on themselves, like actors in a bad play. There is no genuinely experienced interaction. The poses they assume are vacuous and revealing at the same time. Precisely because these men, women and children scarcely display any emotion, they arouse our yearning for warmth, intimacy, and symbiosis. In short, the longing is evoked by exactly that which is not visualised in the drawing itself. You could say that, in doing so, Muskee uncovers human failure and the inability to escape from the subconscious, the servility of custom, the habituation, the cliché, and self-evident authority. But, at the same time, it also demonstrates that we want to see in his drawings something that we miss – protection, sympathy, emotion, contact.