Flyvefærdig (Flight-ready) is an impressive collection of Ole Ahlberg’s paintings, including both his early work and many of his Tintin paintings. He writes in the introduction, ‘I was rejected and rejected, but I was never in doubt, and never really had any choice. The artist is an artist precisely because he is driven by an inner necessity. The artist keeps searching restlessly until he finds his own language. It was quite simply beyond my control, and defied all reason.’ It is this single-mindedness that has led to his unique trademark style and subject matter.

Flyvefærdig (Flight-ready) is an impressive collection of Ole Ahlberg’s paintings, including both his early work and many of his Tintin paintings. He writes in the introduction, ‘I was rejected and rejected, but I was never in doubt, and never really had any choice. The artist is an artist precisely because he is driven by an inner necessity. The artist keeps searching restlessly until he finds his own language. It was quite simply beyond my control, and defied all reason.’ It is this single-mindedness that has led to his unique trademark style and subject matter.

In an introduction to Ahlberg’s work, his colleague Tom Jørgensen has written the following commentary, well worth reading in order to understand the significance of the Tintin paintings.

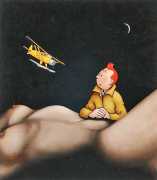

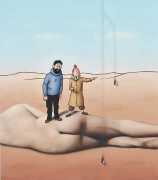

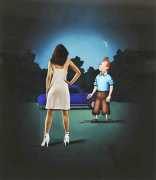

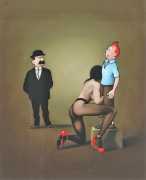

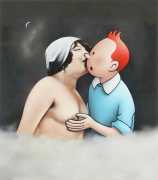

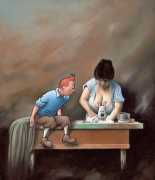

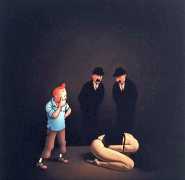

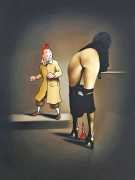

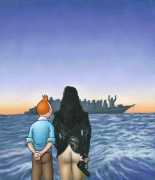

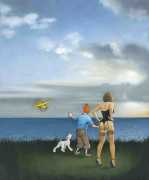

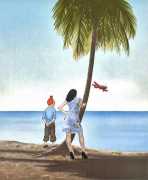

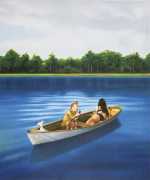

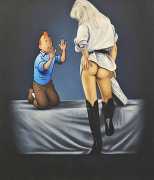

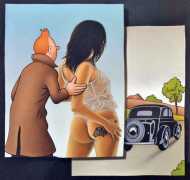

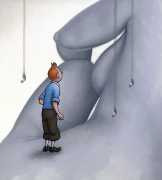

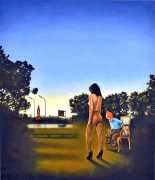

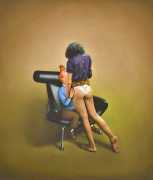

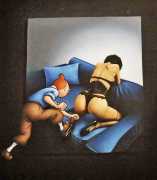

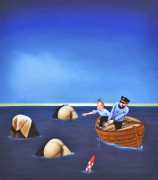

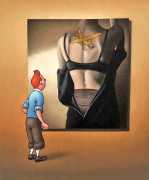

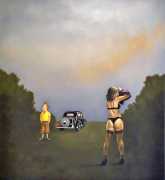

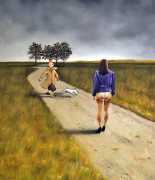

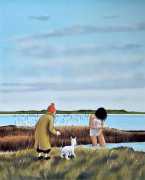

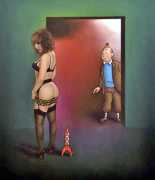

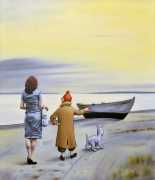

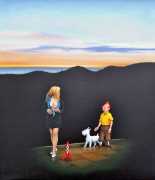

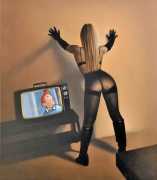

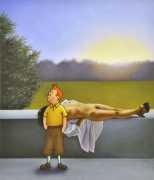

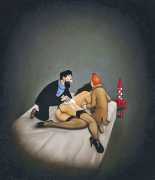

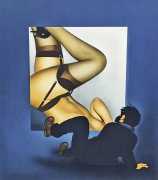

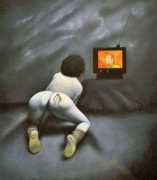

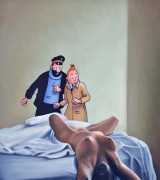

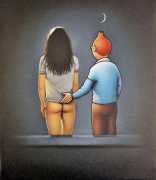

The cartoon character Tintin is the embodiment of goodness and purity, but in Ole Ahlberg’s art a different and less traditional side of the beloved character is revealed – a voyeur who either observes, or almost involuntarily gets involved in, various erotic situations. The contrast between the cartoon universe and the intriguing eroticism and nakedness entices the viewer and causes us to ask questions. Why does innocence find itself in these erotic situations? Does it get into them unintentionally? Did it deliberately pursue them? And what are we supposed to think about what we see?

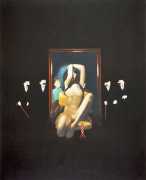

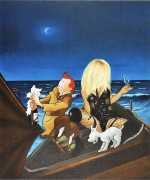

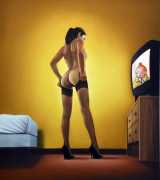

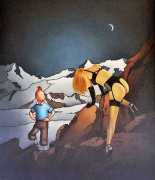

This is how Ole Ahlberg provokes us with his images while showcasing his talent as a painter, able to paint anything but who chooses to paint Tintin. He utilises the difficult techniques necessary for his ultra-precise and realistic imagery, and his paintings containing naked human bodies are almost like photographs. The lighting is of great importance when creating light and dark scenes. The Tintin paintings are often very dark and sinister, perhaps because the drama takes place in dimmed bedrooms, but also because Ahlberg’s style is inspired by the great baroque masters of clair obscure. Ole Ahlberg’s artistic inspiration is firmly rooted in surrealism, but he adds his own twists and turns.

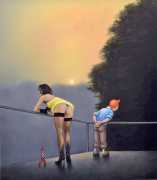

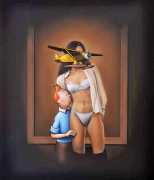

Not many artists display the patience and talent of Ole Ahlberg; he is in full control when he paints the smallest detail. Nevertheless, Tintin appears perfectly cartoonish and genuinely awkward in the adult universe. Ahlberg is able to meld together two completely different worlds without making it contrived. It is as if Tintin has jumped straight from the pages of the comic books and into the paintings, where he is faced with an unfamiliar eroticised world. The purity and innocence of the untouchable Tintin, every mother-in-law’s dream, is inserted into a sexual context where he suddenly becomes a man of flesh and blood who is allowed to follow his instincts surrounded by childhood symbols, including a very phallic rocket. This extraordinarily virtuous cartoon character is confronted with very real women dressed in provocative lingerie. With great astonishment, perhaps even outright shock, Tintin gazes at this abundance with an expression often taken from the real comic books, which reveals that he is a complete stranger to eroticism.

Ahlberg has created a universe where the baroque vanitas symbols, such as peeled lemons, hourglasses, unlit candles and skulls, have been replaced by a more contemporary repertoire, the most obvious difference being between things and people from the ‘real’ world bumping up against comic strip characters. His scantily-clad women, swans, porcelain objects and clouds are painted in a convincing lifelike manner while the comic strip characters are painted with a clearly defined outline that makes them appear flat on the canvas – a contrast which is almost tangible.

Ole Ahlberg’s motifs are mostly about eroticism. Being a sophisticated artist, he never allows his pictures to become too lewd or carnal in nature, but somehow finds a way to encourage the viewer to imagine the suggestive narrative. Eroticism is often a pretext for political commentary and a deeper epistemological investigation, but Ole Ahlberg prefers the black humour and mysteriousness of Magritte to the theatricality and surrealism of Dalí.

If the props Ole Ahlberg often places in his pictures are a solid symbol of innocence, then it’s a different matter when it comes to the figure of Tintin, who has become a kind of trademark for the artist. Tintin is a completely fictitious person, plus he’s a very special type, without even an inkling of a love life. With the exception of the opera-singing, bosomy Milanese nightingale Bianca Castafiore, women are by and large missing from Tintin’s universe. Even the heavily drinking and constantly cursing Captain Haddock shies terrifyingly from Castafiore’s advances, which are more a publicity stunt than a real declaration of love. Ahlberg places this virtuous comic strip figure in situations where he is confronted with very corporeal and scantily-clad women. With wonder, or maybe shock, Tintin stares at the forbidden fruit. His facial expressions, often taken from episodes in actual comics, reveal that all this eroticism is completely alien to him. Ole Ahlberg leaves no room for doubt, emphasising that Tintin is fictitious, depicting him using Herges’ sharp, black contours in contrast with the rest of the painting.

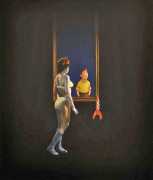

Eroticism in Ole Ahlberg’s paintings is rarely spelled out. In one of the best Tintin paintings we see the young journalist incredulously regarding the red and white space rocket from Destination Moon placed under the skirt of a beautiful woman. Ahlberg presents us with an open-eyed Tintin, a rocket, and a woman’s lower body, enticing the observer to become a co-creator by conjuring up the erotic exploit from their own subconscious. The artist draws on the age-old truth that the most sex-fixated people on earth are the puritans, who can find sexual references in even the most innocent motifs.

Flyvefærdig was published in a limited edition of 100 copies, and although the book is now out of print examples of Ahlberg’s work are available from the Artsy website here.