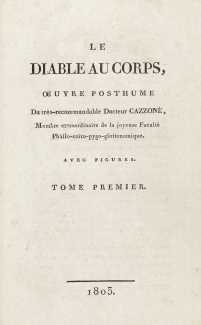

Le diable au corps (Devil in the Flesh) was the last work, published posthumously, by André-Robert Andréa de Nerciat (1739–1800), soldier, poet, composer, playwright and novelist, and a spy under both the Ancien Régime and the Republic. Nerciat travelled to countries throughout Europe during the course of his busy, sometimes turbulent career, and spent most of the last two years of his life in prison after being arrested by French forces in Italy in 1798, probably for his activities as a double agent.

He is mostly remembered today for his libertine writings, starting with Félicia, ou mes frédaines (Félicia, or My Frolics) in 1775. A partial version of Le diable au corps, consisting of about a quarter of the finished novel, was published in 1789, as Les écarts du tempérament (The Deviations of Temperament), temperament being a euphemism for randiness.

Like the Marquis de Sade’s La philosophie dans le boudoir of 1795, Le diable au corps, allegedly written by the late Docteur Cazzone (cazzo is Italian for cock), is presented as a pornographic closet drama, not intended to be staged. Unlike Sade’s collection of dialogues, however, Nerciat’s narrative contains no overt acts of cruelty and no long philosophical dissertations. Instead, we meet a fairly large cast of lecherous characters, starting with a beautiful Marquise and including assorted friends, acquaintances, domestics, tradesmen, clerics, and others. A number of them have suggestive names, like the Comtesse de Motte-en-Feu (mons on fire), the Comte de Molengin (soft engine), the young servant Joujou (plaything or toyboy), and the bisexual hairdresser Belamour (beautiful love). In a long series of scenes and a variety of combinations, the characters gossip, flirt, engage in verbal sparring, recall past carnal encounters, and have all kinds of sex with each other.

Like the Marquis de Sade’s La philosophie dans le boudoir of 1795, Le diable au corps, allegedly written by the late Docteur Cazzone (cazzo is Italian for cock), is presented as a pornographic closet drama, not intended to be staged. Unlike Sade’s collection of dialogues, however, Nerciat’s narrative contains no overt acts of cruelty and no long philosophical dissertations. Instead, we meet a fairly large cast of lecherous characters, starting with a beautiful Marquise and including assorted friends, acquaintances, domestics, tradesmen, clerics, and others. A number of them have suggestive names, like the Comtesse de Motte-en-Feu (mons on fire), the Comte de Molengin (soft engine), the young servant Joujou (plaything or toyboy), and the bisexual hairdresser Belamour (beautiful love). In a long series of scenes and a variety of combinations, the characters gossip, flirt, engage in verbal sparring, recall past carnal encounters, and have all kinds of sex with each other.

Le diable au corps appeared in two different printings in 1803, one in three volumes and the other in six, but both containing the same twenty highly erotic engravings. The illustrations are unsigned, but have reliably been attributed to Claude Bornet.

We are very grateful to our Texan colleague Phyllis Eccleston for the research and images presented here.