In 1906 a book was published which purported to include a true account of the scandalous Order of Aphrodites. In Les sociétés d'amour au xviiie siècle (Secret Societies of the Eighteenth Century), ‘Jean Herviez’ (aka Raoul Vèze) wrote:

In 1906 a book was published which purported to include a true account of the scandalous Order of Aphrodites. In Les sociétés d'amour au xviiie siècle (Secret Societies of the Eighteenth Century), ‘Jean Herviez’ (aka Raoul Vèze) wrote:

In Paris there were secret societies whose members met to make love in special establishments devised by refined debauchees. Such were the Aphrodites, under the patronage of the Marquise de Palmazère, whose headquarters remained in Paris until the Revolution, when most of its members dispersed, either to have their frivolous heads chopped off, or to pursue their activities elsewhere.

It was not be easy to be accepted by the Aphrodites, and it was expensive. Every new member of the Order was expected to make an entrance gift compatible with his financial status. Bad debtors were pursued relentlessly, but as soon as the question of striking them off the roll arose, they generally paid up on the spot, neglecting all their other debts rather than relinquish the extraordinary pleasures afforded by this unique club.

The Aphrodites had a special ‘country house’ near Montmorency, with gardens specially planned for amorous pastimes. The site was well hidden from the outside by high walls. Inside, the grounds were cunningly divided into woods, shrubberies, mazes, and groups of pavilions. The central building, or hospice, was built in the style of a pastoral retreat; the dining-hall representing a copse with hand-painted branches curving up to a blue glass dome. Lawns, tree trunks and marble balustrades were cleverly disposed so as to give guests the impression that they were dining in the gardens of a château.

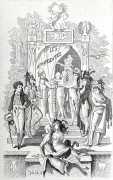

Membership was limited to two hundred adepts from the aristocracy and high-ranking clergy. Aspirants were thoroughly examined during a difficult amorous test that lasted for three hours, presided by dignitaries who awarded crowns to the victors. New members who failed to win seven crowns within the three hours were not permitted full membership. The admittance ceremony was a splendid affair, culminating in a fête worthy of a Roman bacchanalia.

The journal of one of the female Aphrodites has been preserved. This lady documents a detailed list of her 4,959 amorous rendezvous over a period of twenty years – not excessive when one considers the club’s reputation. This includes 272 princes and prelates, 929 officers, 93 rabbis, 342 financiers, 439 monks (nearly all Cordeliers, with a sprinkling of ex-Jesuits), 420 society men, 288 commoners, 117 valets, two uncles and twelve cousins, 119 musicians, 47 Negroes, and 1,614 foreigners.

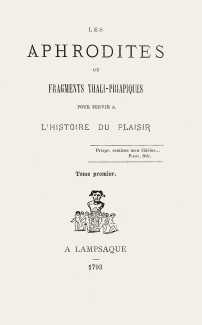

This account was subsequently repeated in later ‘historical’ surveys, including Nina Epton’s Love and the French (1959), but as with so many similar stories it is pure fiction. The fiction in which this one originated came from the fertile imagination of André Robert de Nerciat, his Les Aphrodites, ou fragments thali-priapiques pour servir à l'histoire du plaisir (The Aphrodites, or Thali-priapic Fragments to Document the History of Pleasure), published in 1793.

Nerciat (1739–1800) was a soldier, poet, composer, playwright and novelist, and a spy under both the Ancien Régime and the Republic. He travelled to countries throughout Europe during the course of his busy, sometimes turbulent career, and spent most of the last two years of his life in prison after being arrested by French forces in Italy in 1798, probably for his activities as a double agent. He is mostly remembered today for his libertine writings, including Félicia, ou mes frédaines (Félicia, or My Frolics) in 1775, Le diable au corps (Devil in the Flesh) in 1789, and Les Aphrodites.

These eight engravings and two frontispieces (one for each of the two volumes) were engraved by Freudenberger for the 1793 edition of Les Aphrodites, and subsequently re-engraved by Félix Lukkow for a new edition in 1872.

Les Aphrodites was published ‘A Lampsaque’ (The ancient Greek city of Lampsacus, now Lapseki in northern Turkey), but actually Brussels in Belgium, to avoid French censorship.