In the extended series of drawings, watercolours and oil paintings titled La Tregua Fecunda (The Fertile Truce), made between 2015 and 2018, Ariel Cabrera Montejo explores an alternative history of the period in Cuba between 1878 and 1895, during which the unification of the island started to take place. The Peace of Zanjón in 1878 put an end to the Ten Years’ War, but the residual issues of slave emancipation and increasing involvement of the United States in the local economy made for an unsettled peace. The new freedoms granted by the Zanjón Pact led to the formation of reformist parties such as the Liberal Party and the Constitutional Union Party. At the same time the Cuban community residing abroad began to organise and unite thanks to the work of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, founded by José Martí and Carlos Baliño, preparing for a new fight for independence.

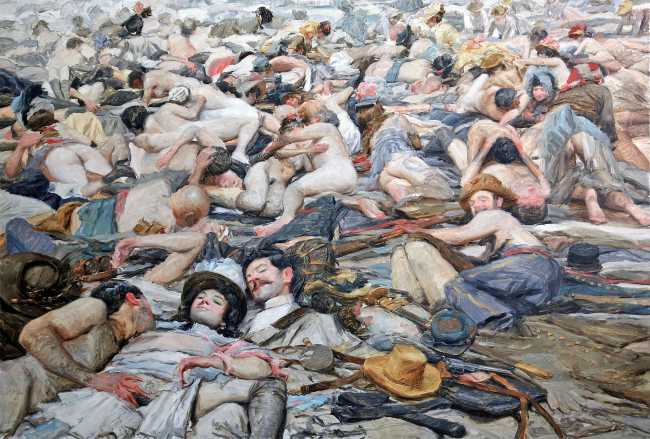

Between the 1870s and 90s three generations of Cubans fought to free Cuba from colonialist Spain, and more than a century later no other historical narrative is as beloved and ritualistically recited in the island as is the story of Cuba Libre and the citizen-soldiers or mambí. In town festivals and cartoons, in textbooks and hymns, even on the national currency, the mambí is the foremost icon of Cuba’s past and present. While the mambí nominally had a military role, much of the time was spent waiting to find out what that role involved, or even which group was deserving of allegiance.

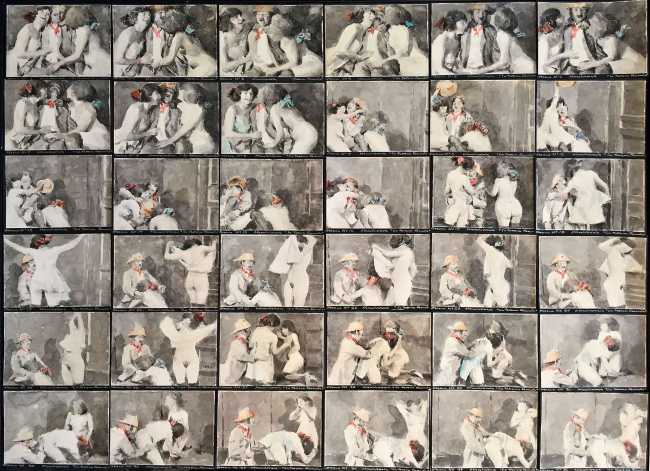

The more mainstream Cuban painters of the end of the nineteenth century who are Monejo’s references – Armando Menocal or Leopoldo Romañach – would never have painted erotic scenes like Montejo’s; they were too busy depicting military heroicism. Monejo imagines an alternative past, using paintings and photographs of the period as source material to look at how life might have been in the long periods between active military duties. His version is truly fecund, a battlefield of eroticism.

In La Tregua Fecunda the narrative of pleasure displaces that of military ideology. Sex becomes almost the primary space for rebellion, given the seeming suspension of time and the mediocrity of the available options. No artist at the time would have thought of using impressionist narrative techniques to imagine the Tregua Fecunda or mambísa life like Ariel Cabrera Montejo. This is the anachronistic effect of his painting – his disrespect for the rules of art history. His version of Cuban history is both transgressive and poetic.