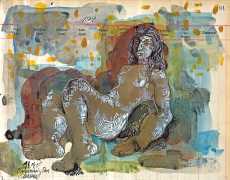

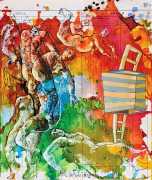

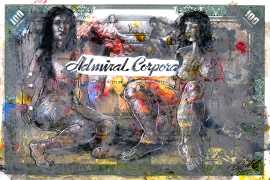

As we shall see from his responses to interview questions below, Thomas Gatzemeier has always been something of a rebel, a tester of boundaries, and this is nowhere more true than his lifelong experimentation with mixing styles, subjects, and media. As with his paintings and drawings, we show here a generous selection of his mixed media artworks, showing how he uses found base material including music scores, leaves from nineteenth century encyclopedias, and old ledger books, and embellishes them with ink and colour to produce throught-provoking combinations of figures and history.

Again these artworks are in chronological order, starting with ink drawings from 1984 and colourful Picasso-esque creations from the mid-1990s. Then he uses pages from a French work on ancient Egypt for a series of ink drawings on a classical theme, before starting around 2000 to use old German business ledgers showing Soll (Debit) on one side and Haben (Credit) on the other.

While Gatzemeier’s work has always revolved around people and their relationship with the world, around Eros and Thanatos, violence, suffering and sensuality, the exploration of physicality increasingly disappeared from the artist’s pictorial world after around 2017. On the one hand, as he explains, he was tired of constantly having to justify and explain why he depicted naked people, and to balance that he rediscovered the depictions of nature that were familiar to him through reproductions in his parents’ house. Since then, his extensive cycle of works collectively titled ‘Sammelsurium’, loosely translated as ‘hodgepodge’, continues to be created, associating traditional art imagery with contemporary real-world objects.

In 2012 and 13 Gatzemeier was interviewed several times about his work; here are some of his replies.

It feels like you have always been someone who tested boundaries, both artistically and socially. Why do you think that is?

I suppose it’s my attitude, it’s just how I am. I don’t conform to everyone and everything. I always do what I want to, and not what others expect of me. Back in the 1980s I enjoyed provoking. It was very different then than it is today, much easier. Today, you run into mountains of cotton wool with art. In the past, you stuck your finger out and someone always bit it, but that also meant that you were perceived as an artist. Today the artist is just a trading number on the mass market of tastes. It should really be about art, but demand and prices obscure a lot.

Why is it that you only portray women in most of your pictures?

Because they are more beautiful, of course. Men have some god-given design flaws. What also appeals to me about the depiction of women is their vulnerability, and to some extent their ephemerality.

Your pictures show a lot of bare skin. Would you call your art erotic?

My pictures are not erotic. They are sensual. Eroticism is aggressive and embodies an obsession. For me, sensuality is associated with melancholy. My naked models don’t pose for the viewer; they rarely look at them directly and invitingly. The women are within themselves. We are merely observers of their beauty.

How do you find and relate to your models?

Well, it’s very different than how it used to be, and very different in Saxony than in the West. In the West you can’t find models; everyone is prudish. In the eighties and nineties students would sit for an evening for 30 marks. I know a woman who posed for money five years ago; she called me recently and asked if she could pose for a drawing as she didn’t have one of herself. I thought that was nice. Another of my models lives in Karlsruhe, but comes from the East and was familiar with the nude beaches on the Baltic Sea.

How did you get into nude painting?

I was brought up in the Catholic diaspora in Saxony. We always went to the museum, and as a little boy I stood in front of a Venus by Giorgione and asked my mother where that woman was now. She said the picture was painted in 1400 or so. I somehow became aware that the woman stays there. Freezing time is the main motivation behind my nude painting. Self-reflection is also part of it, because part of freezing time is the question of dying. I was with my mother until her last breath, and I also know her photos of her as a girl. It is a past life that has been recorded for posterity. Being able to do that is the greatest privilege in art.

Do your audience see it the same way?

In West Germany nude painting is difficult to sell. Customers don’t know how to deal with it. This has caused me problems with some of the galleries I work with, because they don’t have the customers for them. At least in the Swabian region, I can’t find anyone who wants a nude. They’re happy to buy ironwork, abstractions, safe paintings. The dictatorship of abstraction really still reigns. They haven’t got over it yet. They’re still in post-war art.

Do you concern yourself with current trends in art?

Only in passing. My bon mot is that I’m not interested in art, at least not in the way that I might go to art fairs and try to catch a glimpse of trends. I’m fortunate that I don’t have to serve a market because I don’t have one in that sense. But I do have an audience of real enthusiasts, which thank god does not include art speculators.

So what do you see as your main purpose?

I see myself as a service provider. Art must be communicated somehow. That is my cultural mission.