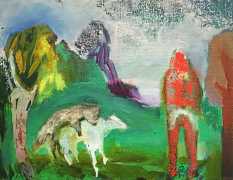

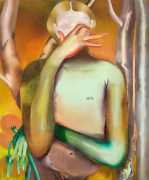

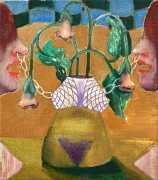

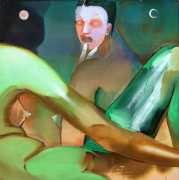

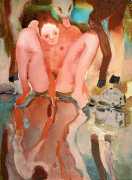

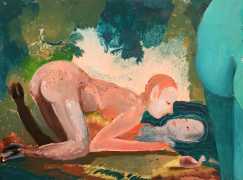

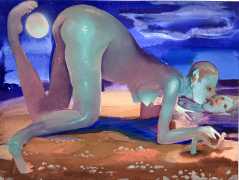

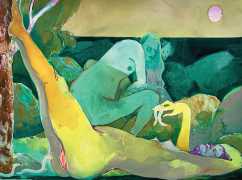

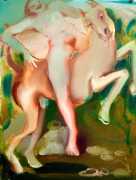

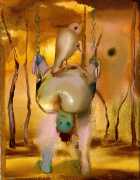

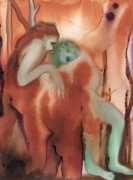

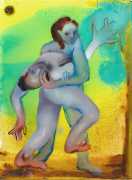

Elizabeth Glaessner’s paintings are bold and powerful, with a constant theme of surreal entwined bodies and limbs, but are they in the slightest degree erotic? Glaessner certainly addresses issues of power and gender, but interpretation always remains firmly in the eye of the beholder.

In a 2021 interview with Olivier Zahm of Purple magazine, which you can read in full here, Elizabeth Glaessner explained some of her technique and inspiration.

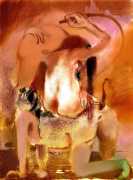

What are these anthropomorphic creatures, the toxic palette, and the orgiastic tableaux telling us? Is it a psychedelic Eden or a bad trip, stories of survivalism or genderless sexuality in these extreme colours? There’s a traumatic aspect to your paintings, tinged with the erotic, because all the creatures seem to be in paradise, but if you look carefully, it’s also very dark. Do you like this ambiguity?

Well, I think it’s very familiar to me.

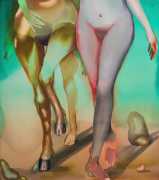

Your paintings mostly feature women who look a bit animalistic. They’re definitely very strong, but they also have very feminine curves and sometimes tits. And an ass, a female ass.

Women that could be men, or vice versa. Gender as a choice. And men have asses too.

Does gender matter to you when you paint?

That’s a good question. It’s shifted throughout my life. I think I was more conscious of it when I was younger. I started out only working with watercolour on paper. Right after college I started making really big watercolours of strong women — like female pro-wrestlers — to counter the big oil-on-canvas paintings made by men.

So your creatures are often quite genderless, expressing something of fluidity and evolution.

I’ve always been interested in fluidity in my work, in terms of both subject matter and materials. I started with watercolours, and I always used a lot of water, and even when I’m doing oils now I pour — so I’m mixing the oils with solvent to create more of a liquid. And naturally the content of the painting is always fluid and morphing, not fully formed or decided until it’s finished.

When we see your paintings, we can feel something of an evolution of sexuality, too, which adds to the mystery. Regarding the current sexual revolution, would you say that your painting expresses these new erotic possibilities?

I’m all for sexual liberation and being able to express and explore this freely –especially in America there’s so much stigma when discussing sexuality. It’s absurd. I think about breaking that psychology down in my paintings. I think there’s so much power in sexual liberation, and it can be dangerous to not express that.

And when asked about her influences ahead of a recent exhibition at New York’s PPOW Gallery, Glaessner expanded on her artistic vision:

I was exposed to all the sadistic tendencies of Catholicism in my upbringing, so that ornate and often grotesque imagery is burned in my brain. And then my grandparents on my dad’s side are Austrian Jews who fled to South America right before the Nazis invaded Germany. I’m not interested in illustrating this history, but I do think that my experiences have shaped my visual language. I make a lot of my decisions as I’m painting, so I leave room for the subconscious and the absurd to help shape the narrative.

I’m all over the place in terms of inspiration, depending on what I’m making. I’m been curious about the representation of gender and sexuality throughout history, so recently I’ve been looking at seventeenth century Japanese shunga prints and paintings, Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for The Yellow Book, ancient Mesopotamian artefacts, Egyptian vase painting, medieval folkloric prints and drawings.

Most recently I've been researching folklore and imagery focused on riders. From the power play between Phyllis and Aristotle to the phenomenon of ‘horse girl energy’; I'm interested in the psychological and physical sensations that the rider experiences when assuming the dominant position, but also how that position has been used in the past and present as a form of punishment and repression.

There’s a thread of personal narrative running through all my work, but for the most part I’m thinking about a parallel space that is reminiscent of but not morally subjugated by ours. In terms of gender, the figures are fluid, and the groupings represent protection and exploration.