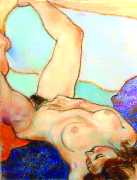

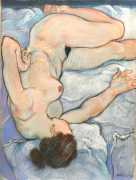

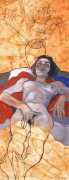

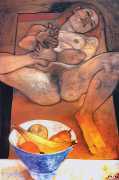

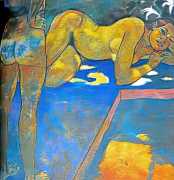

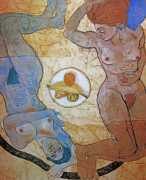

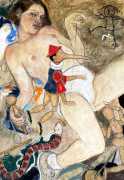

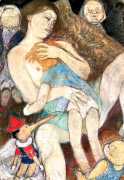

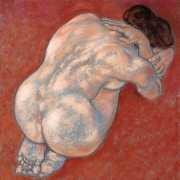

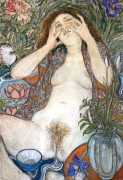

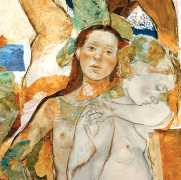

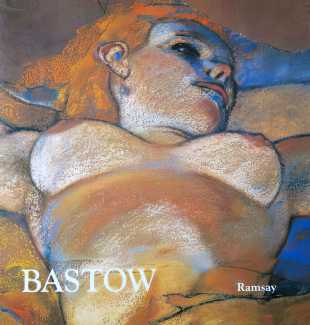

In 1991, when the Paris publisher Éditions Ramsay published a collection of Michael Bastow¹s pastels titled simply Michael Bastow: Pastels 1986–1991, this was the technique and subject matter that the artist was known for – technically accomplished, colourful, artistic studies of naked women in a style not a million kilometres from Dégas or Klimt. He sometimes included a self-portrait, to demonstrate that he had thought about the relationship between artist and subject, yet though skilled and eminently saleable Bastow was still playing things fairly conventionally and safe.

In 1991, when the Paris publisher Éditions Ramsay published a collection of Michael Bastow¹s pastels titled simply Michael Bastow: Pastels 1986–1991, this was the technique and subject matter that the artist was known for – technically accomplished, colourful, artistic studies of naked women in a style not a million kilometres from Dégas or Klimt. He sometimes included a self-portrait, to demonstrate that he had thought about the relationship between artist and subject, yet though skilled and eminently saleable Bastow was still playing things fairly conventionally and safe.

The publisher asked Bastow’s friend the artist Roland Topor to write an short introduction to the book, most of which today reads as cringingly sexist and condescending: ‘“The most beautiful girl in the world can only give what she has,” states the popular saying, somewhat self-evident, more subtle than it seems when it comes to the disproportion between desire and its object. By definition, the most beautiful girl in the world has everything it takes to inspire desire, and gives pleasure by satisfying it.’

Yet there is a more subtle and honest analysis later in Topor’s introduction, where he writes:

In the 1960s eroticism became a kind of cliché, a sophisticated product of low-end marketing. We saw the proliferation of a whole post-surrealist bazaar, cluttered with garter belts and cheap fantasy. The fetishism of high-heeled pumps and sadomasochistic sex-shop accessories had, without our noticing, replaced the elementary truth of bodies. Eroticism had been reduced to a photographer’s gimmick for speciality magazines, and the famous sexual revolution has primarily served to sell films and paper to the general public, too miserable to be demanding, too consumerist to differentiate.

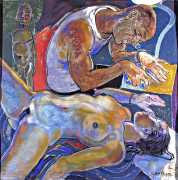

Michael Bastow’s pastel technique has been refined over the years, to the point of becoming prodigiously complex, but his mastery of execution never distracts him from the initial wonder of discovery of the naked female human body. And he has found his own way of engaging with it. What in the hands of many painters is a certain power over the model’s body, is rather different in Bastow’s work. He ceases to be a privileged voyeur, an impassive onlooker, a stubborn creator obsessed with creating a masterpiece. In many ways he is the eternal loser in the close combat he engages in with his subjects. The imaginary space where he believed he had imprisoned them also sucks him in. They have plenty of time to take revenge, to punish him for having looked at them.

I believe that Michael Bastow masterfully visualises the torment of an artist who seeks, thinks about, and expresses, the reality and true beauty of eroticism.