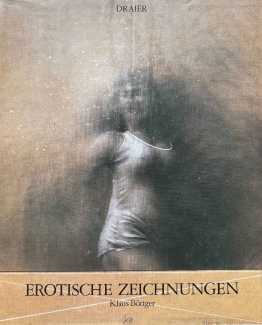

The first, and most important, collection of Klaus Böttger’s erotic artwork was published by the specialist publisher Draier Verlag, based in Görbelheimer Mühle near Friedburg, north of Frankfurt am Main. In addition to the artwork, the book includes a general introduction to the place of erotic art in the art world, and an almost impenetrable and pretentious analysis of Böttger’s work by the art critic Jürgen Seuss. Here is a flavour:

The first, and most important, collection of Klaus Böttger’s erotic artwork was published by the specialist publisher Draier Verlag, based in Görbelheimer Mühle near Friedburg, north of Frankfurt am Main. In addition to the artwork, the book includes a general introduction to the place of erotic art in the art world, and an almost impenetrable and pretentious analysis of Böttger’s work by the art critic Jürgen Seuss. Here is a flavour:

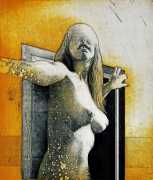

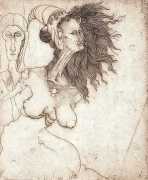

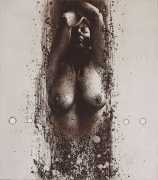

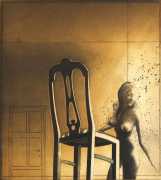

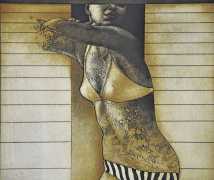

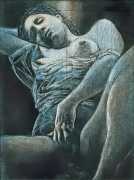

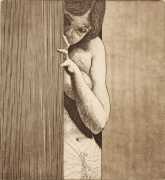

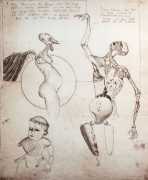

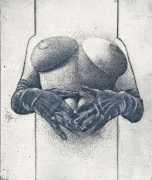

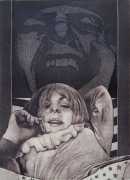

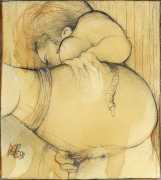

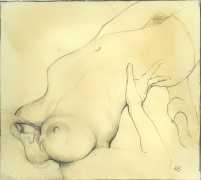

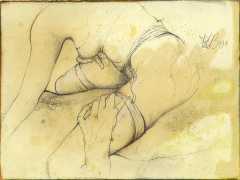

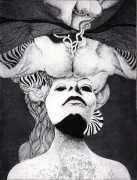

The line swings, breathing a sigh of relief, freed from the web of intellectual constraints, into the image, into the surface, connecting, meeting with other lines, developing into all kinds of forms, across the centuries of art, towering up to baroque objectivity, revealing voluminous forms and physicality with voluptuous gestures, with pleasure in the saturated image, incorporating the brokenness of the material and the scattered accidents of destruction as moments of mystification, but also as references to existentially conditioned floral ornamentation, dabbing element upon element of the idea into a motif-determined image. The line becomes a point, a spot, a torn straight line, a surface, it disposes itself in darkness and wanders into light, builds up and destroys, forms shapes according to the imagination of a flâneur, preserves faces and scrapes the detail from the overabundance of sensuality and experience. The result is an image of concrete prose: Klaus Böttger, the storyteller.

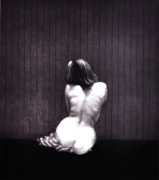

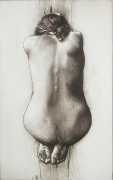

Böttger’s images, prime examples of contemplative prose, play around the single or multifaceted, incommensurable object in aesthetically sophisticated form, critically defining it or merely interpreting it, elevating it to tangible sensuality or presenting it in its monolithic solidity with the sign of its transience. Images emerge in which the imagination engages experientially, the fictitious partner as viewer is invited to a masterfully crafted conversation with the gesture of the gourmet who recommends himself to his guest with the aperçu of the master. The images sparkle with expansiveness, do not require consensus, are, in their brilliant concreteness, anticipated arguments that are conscious of their inner and outer quality.

The precise motifs involved are irrelevant. The etched landscape becomes just as much a vehicle for associations of vivid imagination as the portrait of a girl or the erotic drawing. Böttger’s ‘sense of possibility’ results from the realisation that there is no aesthetic no-man’s-land; all possibilities lie in the visible, in the representable.